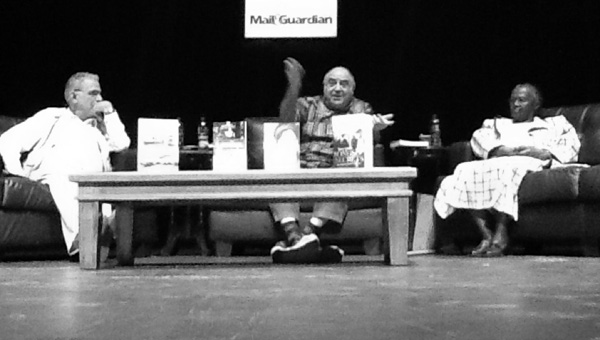

Stories of exile, with Ronnie Kasrils (chair), Lauretta Ngcobo, Liepollo Lebohang Pheko, and Barry Gilder.

Session 13: Sunday 2 September, Market Theatre

NEDINE MOONSAMY

Writer and retired cabinet minister Ronnie Kasrils (centre) in public conversation with fellow returned exiles Barry Gilder and Lauretta Ngcobo

Before the beginning of the final session, festival co-director Corina van der Spoel passes a short vote of thanks to all involved. She remarks that it has been interesting to listen in on ideas that shape us as a society. She introduces the chair of the session, Ronnie Kasrils, by highlighting some of his formidable contributions as both a politician and a writer.

Kasrils argues that exile writing, and the memoir in particular, have undoubtedly enriched our history. He frames the session by making reference to Milan Kundera, who valued memory as a weapon against the oppressive forces of power. This sentiment, he suggests, is apt in relation to our young democracy.

He congenially introduces the panelists, Lauretta Ngcobo and Barry Gilder. Liepollo Lebohang Pheko was also listed as a member of this panel but she is absent and no mention is made in this regard. Kasrils briefly introduces us to the premises of Lauretta Ngcobo’s edited volume, Prodigal Daughters, a compilation of accounts from women who lived in exile; and Barry Gilder’s autobiography, Songs and Secrets: South Africa from Liberation to Governance. He finds them books of great impact and firmly encourages the panelists to speak about their texts.

Ngcobo immediately delves into her personal experience of exile, outlining the fact that exile stories have an intimate – if not inherent – relationship with autobiography. She recalls the incredulity of realising that she would have to flee the country and how it felt like a very inopportune moment that made no sense at all.

“But”, she says, “the step I took the next morning took me into a world I never thought I would experience”. In her own contribution to Prodigal Daughters, she uncovers how exile “revealed so much about me … about how ignorant I was”. She reads her naïveté and sense of isolation as part of the systematic violence of apartheid that aimed to keep its black subjects in the dark.

Barry Gilder argues that Songs and Secrets is not really about exile. He jokes that he may be on the wrong panel. His aim was to capture the complex process of transition from exile to homecoming rather than to recollect experiences from his time outside of South Africa.

This uncovers what is exceptional about exile – it is always a teleological journey informed by the hope of return. This point is reaffirmed when Ncgobo says exile felt much like an “escape and an acceptance of defeat”, but one that allowed her to draw inspiration from the fact that she could return to continue the fight sometime in the future.

In response, Gilder agrees that going into exile initially felt like defeat, but in retrospect he now sees it as part of the specific nature of the struggle. He argues that apartheid forced it upon us to extend the frontiers of resistance, and exile was just another site from which to continue the struggle.

Kasrils interjects by suggesting that the entire point of exile was to organise and strategically plan resistance movements from outside the country. He brings Ken Keable’s compilation, The London Recruits: The Secret War Against Apartheid into the conversation by suggesting that these accounts serve as evidence of how South Africans in exile sought to interrupt the power structures of apartheid from the outside.

Kasrils says that the book captures the experiences of many young English citizens who were recruited by South Africans in exile to enter the country on their behalf. Those in exile felt a need to reinvigorate the people of South Africa via propaganda and they employed young white foreigners (who entered the country as tourists) to smuggle in pamphlets which they would then distribute illegally.

Next, Kasrils reads from the City Press review of Gilder’s Songs and Secrets. The reviewer, Mathatha Tsedu, describes Gilder as “an intense and tortured soul with niggling feelings of wasted sacrifice”. Gilder says he has received criticismof a similar kind from Lindiwe Sisulu. She felt that Gilder wrote two books: she enjoyed the book up until the point where he comes home but the second half of the book – where he recounts life in South Africa – she found too brutal. He says he wrote the book in order to capture the nature of struggle itself. He wanted to trace the trajectory of ideals and romanticism fading into reality. He empathically declares that he is not an embittered citizen. He does not appreciate “finger pointing” and feels that we should not become oppositional and derisive.

Kasrils then asks Ncgobo to share her experiences of homecoming with the audience. For Ncgobo, coming home felt like a victory because she anticipated the day for so long. But when she returned, she realised she had come back to questions and alienation. She felt a sense of her own irrelevance in relation to the people around her.

This nagging concern about personal relevance, she suggests, was part of the motivation behind Prodigal Daughters. There was a need to justify the experience of exile in view of the fact that no tangible or material evidence of their sacrifices could be ascertained in the South Africa to which they had returned. She argues that they had sacrificed a life in South Africa so that others would “be able to possess a life in South Africa” but it now feels embarrassing and shameful because the delivery of their ideals seems so poor.

The floor is opened for a few brief comments and an audience member recounts the shock of attending a meeting at UJ about the Marikana mining massacre. She found it surreal that people were angry at the unions and the ANC, shouting slogans calling for their demise. She asks the panelists if they feel that the struggle is only just beginning.

Ncgobo offers a prompt, “yes”, in response. She recalls the irony of how she created the expectation of a home in South Africa for her children but this never translated into reality as her daughter felt distinctly out of place upon return. She argues that “no one feels like they belong anymore … no one feels at home”.

Ncgobo implies that belonging is a matter of engagement – she insists that young people have to produce their own leadership to get out of “this mess”. She feels that the youth can sometimes be apathetic in thinking that the battle is fought as every generation must produce its own leaders.

Gilder suggests that problems of post-apartheid South Africa are a continuation of the same struggle. Employing a Marxist framework, he suggests that we have only won a partial and political freedom and that the next step would probably involve economic freedom. Yet, he deflects this progressive outlook by declaring that “what we certainly don't have is ideological freedom” in a tone that suggests this to be the ever-elusive dream of our democracy.

In conclusion, Kasrils expresses great sadness over the Marikana shootings. He draws an uncanny relation between the Sharpeville shootings and the recent ones at Marikana – both of which left him numb and nauseated. He counters Gilder’s earlier remark that there should be no “finger-pointing” by insisting that finger-pointing can create an appropriate amount of moral outrage – a sensibility that is sorely lacking in our current government. In an abrupt and pithy attempt to disarm the pessimism that has infiltrated the space, Kasrils ends with a declaration, “A luta continua ... let's keep the optimism up and the spirits high!”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project