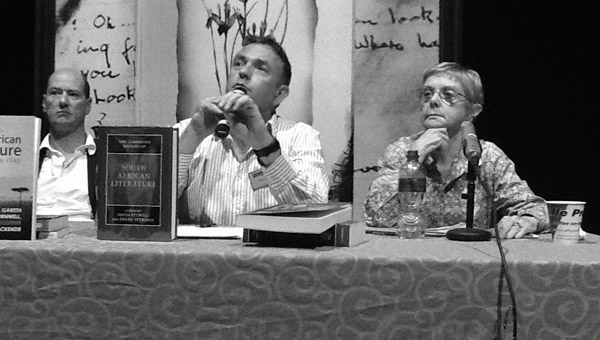

Report on One country, many literatures: looking at South African writing. Michael Titlestad (chair), with Craig Mackenzie and Margaret Lenta.

Session 7, Mail and Guardian Literary Festival, Saturday September 1, Market Theatre.

NEDINE MOONSAMY

Michael Titlestad (centre) listens carefully to a comment from the audience as Craig Mackenzie and

Margaret Lenta ponder weighty critical questions

Darryl Accone offers a brief introduction to the chair, Prof Michael Titlestad of Wits, who then proceeds to introduce the panelists: Profs Craig McKenzie (UJ) and Margaret Lenta (emeritus professor at UKZN). As one of the smaller theatres at the Market, the Laager seems fitting for a trio of literary experts whose familiarity and intellectual engagement evidently precede this panel discussion.

Titlestad suggests that, in keeping with the near-intimate setting, the session will be open to the audience so that dialogue and debate can flow freely about where South African literature is now and the ways in which it is developing.

Titlestad, Mackenzie and Lenta have all been directly involved in the production of South African literary histories, and by way of introduction Titlestad talks about his experience as a contributor to the recently published Cambridge History of South African Literature (ed. David Attwell and Derek Attridge).

Well-aware and skeptical of the canonical power of this authoritative tome, Titlestad says the history was informed by a desire for inclusion. Given the nature of South Africa’s fragmented history, he argues, various traditions must be tracked in order to establish underlying connections between them.

Titlestad finds the Cambridge history ambitious and well-intentioned but argues that its success is questionable. On a more general note, he proceeds by challenging the nationalistic means by which literature has come to be defined in South Africa. He argues that in a context where borders are becoming increasingly arbitrary, an over-attachment to the “nation” may not be the most feasible literary endeavour.

As co-editor of SA Lit Beyond 2000, Lenta argues that she and Michael Chapman (fellow co-editor of this anthology) were seeking an appreciable view of an era she typified as ‘non-compulsory literature’. She argues that this collection of essays was largely informed by an overt awareness of liberty that has come as a result of the demise of apartheid, which in turn allows academics and writers the opportunity to be more diverse and less introspective in their approaches toward literature.

Mackenzie argues that The Columbia Guide to South African Literature in English since 1945 (eds. Gareth Cornwell, Dirk Klopper, and Craig Mackenzie) has a much more modest aim. It seeks to document – as concisely as possible – the various shifts and developments in South African literature. Mackenzie addresses the concern that the material may already by out of date by commenting on the overwhelming task of keeping up with contemporary South African fiction.

He acknowledges that the points of departure and ending are extremely arbitrary in the text as South African literature is and will always be an open-ended dialogue. Similarly, he insists that there is a dialogue going on between the three books. Mackenzie says we must adopt an attitude of open-mindedness if we are to foster multilingualism.

As soon as the floor is opened for questions, the sense of a literary culture under threat is pervasive. The first question voices concern about the archival neglect of South African texts, particularly those stemming from the oral tradition. In response, Titlestad talks about the National English Literary Museum (NELM) and how it is currently being upgraded to house more South African material.

Titlestad adds that ideological changes are needed for the archive to become representative of a multicultural heritage. He says the aim of NELM is to protect the archive from being privatised, insisting that access rather than ownership is key.

Responding to the question, Lenta is equally aggrieved by the lack archival preservation and says the oral traditions are currently subject to a state of academic neglect.

Titlestad broadens this out by arguing that this is a challenge for the humanities at large. He argues that the drop in African literature enrolments is alarming and leaves open a visible gap as far as academic engagement is concerned.

Despite the fact that Mackenzie also finds English literature to be a shrinking discipline, he encourages a shift in perception regarding the ways in which young people read and consume literature. He addresses the plethora of popular fiction as a positive representation of a culture that is liberated from a tradition of “serious” literature with a single objective – the end of apartheid.

Alluding to Steve Biko, he argues that people can now write what they like. Yet, somewhat despondently, he admits that despite the relevance of popular fiction, the numbers suggest that people are not buying it. Mackenzie gives alarming statistics about the dire lack of exposure to and consumption of books in South Africa. He insists that we can only become a book-loving culture by exposing children to reading at a young age.

A representative from the Department of Arts and Culture talks about the challenges involved in encouraging the growth of indigenous-language cultures. Concerns are raised about the hegemonic nature of English and about how South Africans seek to address and incorporate its colonial baggage.

Addressing a question about the lack of publishing opportunities for new writers in South Africa, Titlestad insists that publishing houses are not unwilling to publish new writers but are bound by financial constraints that come as a result of exceptionally poor sales.

As the conversation continues, a chicken-and-egg situation emerges: new fiction cannot be produced without readers but readers cannot be produced without exposure to relevant fiction (an impasse more prominent in relation to literature in indigenous languages). The unanimous agreement is that more – and immediate – attention should be paid to the development of literacy in South Africa.

Titlestad interjects by arguing that the book is indeed under ‘threat’ but we need to move towards new forms of reading and seek to reach different constituencies who read in different ways. The aim should not be to resist the shift in reading and the media but to encourage reading and literacy irrespective of the form it assumes. Titlestad suggests that new media may, in fact, help in this regard by making books more cheaply available.

Similarly, Mackenzie believes technology will come to our rescue. He states that music consumption has evolved in order to survive (and thrive) in the digital age and he hopes the same will happen with reading and books.

In response to a question about the gap between “popular” and “academic” perceptions of literature, Lenta closes with an anecdote about a poet who readily claimed the title without ever being published. This poet, she states, would often perform at weddings. She commended this as an example of how literature can be celebrated and enjoyed within society rather than merely having publication as a primary goal.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project