Eusebius McKaiser in conversation with Alan Hollinghurst and Damon Galgut, 22 September 2012, Fugard Theatre

JONATHAN AMID

From left to right Eusebius McKaiser, Damon Galgut and Alan Hollinghurst.

Eusebius McKaiser, prolific Tweeter, astute political analyst and regular contributor to the New York Times, is about to start a discussion of the writing process with two esteemed guests, authors Alan Hollinghurst and Damon Galgut.

Accordingly, the Fugard Theatre is filled to capacity. At just after 16:00 there is a tangible buzz and an air of excitement as we wait for three men on stage, conversing all too quietly and giggling among themselves, to include us, their audience, in the conversation.

Hollinghurst is an award-winning novelist whose most recent novel, The Stranger’s Child, was longlisted for the Man Booker prize in 2011, an award he won in 2004 for The Line of Beauty. The Swimming Pool Library (1988) won the 1989 Somerset Maugham Award and The Folding Star (1994) won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction in 1994.

Galgut, in turn, is the author of several novels, a collection of short stories and a number of plays. Starting with A Sinless Season, he went on to publish Small Circle of Beings (1988), The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs (1991), which won the CNA Prize, The Quarry (1995), The Good Doctor (2003), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book from the Africa Region, and The Imposter (2008). His most recent novel, In a Strange Room, was published in 2010 and was shortlisted for the 2010 Man Booker prize.

While McKaiser often comes across as confidence and assertiveness personified in his television appearances and is certainly ever opinionated in print, his stage manner is surprisingly cool and collected, and he takes a while to get into his stride after he welcomes his two guests. He leads the discussion in a direction that segues subtly from the general to the specific and back again: How, asks McKaiser, do Hollinghurst and Galgut write, and how do they themselves respond to the reception of their work?

A different interlocutor would most likely first have inquired into the process or mechanics of their writing methods, but McKaiser chooses to start with an inquiry into the general reception of both authors’ work. Hollinghurst is up first, and what a treat it is to hear such an eloquent, efficient wordsmith speak. With his perfectly coiffed grey hair and goatee, Hollinghurst strikes you as a writer at ease in his own skin, and his generous but considered answers confirm this impression.

Hollinghurst introduces his thoughts on the reception of his work by suggesting that he feels “disconnected” from reviews of his work after finishing a book: he both knows the writing intimately and is aware of the fact that much of the meaning is yet to be unlocked, even by him, the one who shaped the words on the page.

To the amusement of the audience, Hollinghurst mentions a particular book reviewer, James Woods, who has reviewed four of his last works, each time praising and “punishing” the writer for his perceived literary indiscretions. While sharing this, Hollinghurst cannot help but burst out laughing, perhaps a little surprised at his own candour, and this is a development that continues throughout the hour’s insightful and convivial discussion.

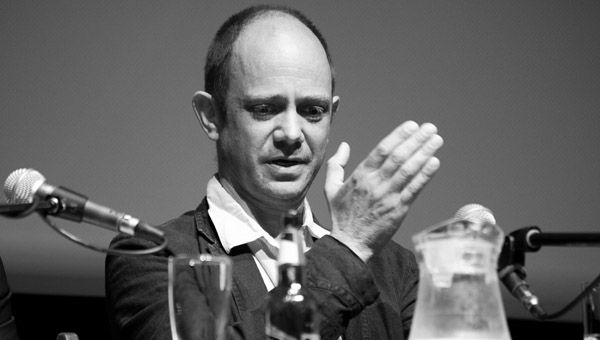

Alan Hollinghurst

Galgut, as opposed to Hollinghurst, is not a conventionally good-looking man. However, he has developed a reputation among the bookish for a particularly charming, disarming kind of nervous energy and rapier wit that never fails to capture the attention of the audience.

Galgut is as much, if not more, to the point in his answers, and when reflecting on his own appreciation of reviewers and critics’ take on his work, he notes how personal correspondence by readers has often elicited some of the finest and “most eloquent” of responses to his work. He finds that critics can often be driven by malice and that they tend to write from a certain place or perspective because they will in turn also be judged according to the position from which they are writing.

These “meta-insights” (a fine observation on McKaiser’s behalf) lead into the question of critical reception - whether something like a right or wrong interpretation of their works exists. Both writers agree that their writings open up (to) a variety of interpretations, but that the “truth-telling” apparatus (both formally and linguistically), the ways in which tangible meaning is constructed, must be illuminated as far as possible. There is also agreement from the two authors that their works are often intensely personal without necessarily being about, or a reflection of, their own experiences.

One feels that this is a point germane to much great literature, and Galgut offers that his ideal reader would be able to produce a reading with which he would not necessarily agree, but which might be shaped by “aims and values” much the same as his own. Somewhat unfortunately, what each author aims or strives for in their writing project is a question that McKaiser bypasses largely.

That said, both Hollinghurst and Galgut are good-spirited interviewees and appear to be enjoying the line of questioning.

McKaiser then quizzes the pair as to their thoughts on the writer as performer in the digital age. In one of my favourite moments in the discussion, Galgut is left perplexed and in doubt about the best way to respond to the question for close on ten seconds. All he manages to do is to smile his oddly delightful, signature “someone get me out of here” smile, after which he pulls up his shoulders as if to say, “I’m here, aren’t I?”

Hollinghurst perceptively points out that the experience of “performing” at book signings and festivals “cannot be endlessly looped” in a digital sense, and that the experience, for him, has a kind of magic in its own right.

Damon Galgut and Alan Hollinghurst

On the topic of editing, and the state of editing in South African literature, Galgut is most forthcoming. He candidly speaks of the frustrations he has experienced with debut novels in particular (which McKaiser labels as being hamstrung by the “good first draft” syndrome) and his own meticulous self-editing skills, honed over years of writing in isolation. At one point, Galgut again has the audience in stitches when he notes how he “fantasises” about “not writing” while arduously slogging away.

Hollinghurst informs us that in his previous career he was an editor in the publishing industry, and that he is “pedantic” in the way he constructs his narratives, taking up to five or six years on average per book. He notes how he worked for what seemed like forever on a book of 280 pages, while a later work took a few years less to complete and tipped the scales at 560 pages.

At various other points in the discussion, Galgut and Hollinghurst have quite a few laughs at J.M. Coetzee’s expense; McKaiser tells us about his first proper interview, with Nadine Gordimer, no less, where she took him to task for his perceived “ageist” line of questioning; all three writers express their views on gay sex.

You had to be there to appreciate fully the delicate balance that was maintained between forthright freewheeling and measured (unhurried, deliberate) Q&A, but the triad of McKaiser, Hollinghurst and Galgut certainly entertained and informed in equal measure.

Damon Galgut

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project