Ashraf Kagee in conversation with Imraan Coovadia, 19 June 2012, Psychology Department, University of Stellenbosch.

WAMUWI MBAO

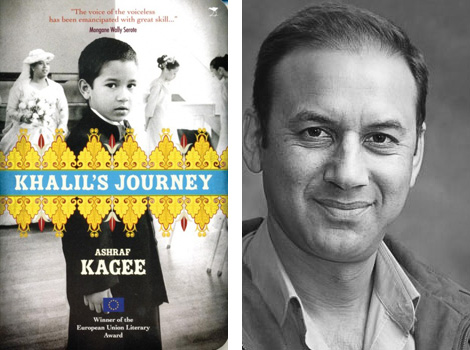

Khalil’s Journey, the debut novel of Ashraf Kagee, is an enigmatic and beguiling work, a novel that has large things to say about little moments in time. Its protagonist is positioned at the apex of the Cape Malay and Indian cultures and the novel traces the span of his 80-odd years of life across the 20th century. It has been lavished with praise of a mostly untempered nature, hailed for its attention to textures and celebrated in ways that suggest that, once more, this is The Novel We’re Looking For.

All that being as it may, Stellenbosch University’s Psychology Department hosted a conversational event where Kagee riffed in supple fashion about his inspirations, his literary musings and everything else that matters when we talk about literature. He was ably assisted in this endeavour by Imraan Coovadia, a novelist in his own right, to whom the Academy pays obeisance in the form of a Creative Writing post at the University on the Hill.

Both writers are welcomed by Leslie Swartz, who introduces them and gives them free reign to conduct the conversation in any way that they like. Although the university’s recently restored Wilcox buidling might be a venue more suited to dry lectures than the sort of literary tete-a-tete we get from Coovadia and Kagee, the two authors, in a disarming eschewal of the usual sit-down format, stand and talk to each other, their repartee an immediately engaging saunter through the questions at hand.

Prompted by Coovadia, Kagee begins by describing the distance between scholarly writing and the crafting of fiction. “Writing in a scholarly way requires a certain kind of discipline, and one writes for a particular audience.” The authors agree that literature allows access to a sort of free indirect realm, with Kagee proposing that “writing as a creative writer or a fiction writer, one can kind of free-associate in a way that you can’t really do when you write a journal article”. The audience, effectively a coterie of people who do and say various things in the Psychology Department, effervesces its mixed sentiments at this statement.

Listening to Coovadia pose his points, one gets the sense (it is by no means a certainty to be taken for granted at these affairs) that he has read the book and read it well. Despite this, he has a tendency to ask baggy questions like: “Psychologists all know about transference and counter-transference. How does that work with novels?” This is the sort of question that tends to elicit tedious run-on responses as the author flails about to soak up every possible meaning. Indeed, Kagee prevaricates for a while before pinning it down. “I think it works and it doesn’t work. People often ask me ‘is this autobiographical’, and it’s a question that all writers get asked at one point or another. The short answer is that no, it’s not autobiographical, it cannot be autobiographical because the story starts at the beginning of the 20th century, at the start of the Anglo-Boer War, and I wasn’t alive then.” This earns a peal of laughter from the audience.

He pauses to let the point steep, before continuing. “So it’s not autobiographical in that way. On the other hand, I found myself trying to imagine what it was like growing up during that period and living through the World wars and the Depression and the Union of South Africa and the Land Acts and all of the political developments that occurred. To that extent, one does try to imagine and make the boundaries between the self and the context be permeable.”

Kagee is very interested, he lets it be known, in tapping historical currents for the guiding trajectory of his novel. He mentions “the sinking of the Titanic, Dr Abdurahman’s lectures to the Cape Town City Council” and other such historical events and points to the way the narrative of Khalil’s Story weaves these facts into its being and allows them to inhabit the work without overwhelming the fictive. “This wasn’t meant to be a political book. In fact, it’s not. The protagonist is decidedly non-political or apolitical. This,” Kagee muses “was probably the case for a lot of people growing up and coming of age in the twentieth century...not everybody was an activist. However, as I was developing the story, I found that it was very difficult, if not impossible, to dislocate it from its social and political contexts, from Apartheid and the machinations of the political events that were occurring over the course of the twentieth century.”

Coovadia proposes, as a way of negotiating the ostensible impasse between the fictive and the historical, that we term the novel a “fictional biography”, and Kagee picks up this gambit and expands it, noting that the work has at its centre the idea of the ordinary: Khalil is an ordinary person to whom various, occasionally difficult things happen. “It’s not an easy life,” Kagee offers, “but he deals with these hard events in the way that ordinary people did. There’s nothing remarkable about this person.” By focusing the narrative through the quotidian experiences of Khalil, Kagee offers a commentary on the lives of those who didn’t have a great deal of influence or power over their societies.

At least half the talk is given over to discussing writerly intention and the liberations of writing in the fictional form. Kagee says he likes “the power of being able to write what I like”, a literary joke which draws a chuckle from the audience. At another point, Coovadia speaks of “the desire for thought on the margins, for thinking outside of those disciplining structures”. It’s clear that for both writers, the creative project is an escape, albeit an escape that brings its own complications.

“There’s a moment where Khalil’s in hospital,” Coovadia begins, “and he thinks that Christian Barnard became very famous for his heart transplant, in a society where the same money spent could have saved tens of thousands of people from disease or starvation.” He proposes that this is a rather radical thought for a person in Khalil’s position to think, and he asks Kagee if this, the kind of thought that would be common wisdom around health professionals nowadays, is not an odd thought for Khalil to be thinking from his historical moment.

Kagee responds with an anecdote about how he was assigned an editor who was useful in pointing out anachronisms like this. He goes into a little soliloquy about rock and roll, and how the latter has an effect on how the characters come into contact with modernity. “There are a couple of instances where it’s difficult to tease out [the difference between] what the narrator is saying and what I’m saying – one of these instances is where certain characters in the book are racist, or prejudiced to different racial or ethnic groups, and I found myself wondering how to say this without the reader thinking this is my own point of view. And this is the challenge,” – he cuts back to Coovadia’s original question – “with what you speak of as transference”.

“One of the things that really interested me as a writer,” Coovadia begins again, “is that a lot of South African fiction is preoccupied with some moment of community that is forever lost – you know, if the government hadn’t levelled those three square kilometres, we would still have a community of some kind – and that feeling is very powerful in this book.” He cites several instances in the book, such as a large extended family sharing a single tap, or another one in which the family shares a nail clipper until some or other character finds this behaviour egregious. He mentions a set of crockery that sits in Khalil’s house, brought back by some traveller from the East, as a way in which the voice makes seen the Indian Ocean trajectories of meaning and cultural exchange.

Kagee’s response is that he was trying to recuperate a world that once existed back into being. “My own personal journey was to go back to the twentieth century and think about how life was different 100 years ago.” He thinks that there was a greater sense of community in those times, whereas today the level of interchange is different. “The sharing of crockery, or the sharing of personal effects, was something that people used to do, whereas things are a bit different today... life is lived a little bit more individualistically.” Kagee confesses that he is fascinated by “that aspect of life from long ago that has been lost as communities become more and more independent”. He confesses to wistfulness, a desire to capture that community spirit as it existed, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Coovadia muses that this revisiting “might direct our attention to other ways of organising property and ownership”.

To emphasise his point, Kagee reads a passage from Bruce Springsteen’s keynote address to the South By Southwest festival:

every musician has their genesis moment . . . Mine was 1956, Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show. It was the evening I realized a white man could make magic, that you did not have to be constrained by your upbringing, by the way you looked, or by the social context that oppressed you. You could call upon your own powers of imagination, and you could create a transformative self. Television and Elvis gave us full access to a new language, a new form of communication, a new way of being, a new way of looking, a new way of thinking about sex, about race, about identity, about life . . . once Elvis came across the airwaves, once he was heard and seen in action, you could not put the genie back in the bottle.

Kagee ends with this enigmatic quote. But it isn’t quite the end, of course. There is a round of questions that lasts twenty minutes or so. Half of them are the sort of meaningless non-questions – “How much of Ashraf Kagee is in the book” – that draw similarly broad and oblique answers. Others bring forth more meaningful responses from the authors.

A woman sitting three or four rows down from me asks Kagee about the makeup of the judges on the panel that awarded him the EU Literary Prize. He replies that they were all South African. Perhaps unsatisfied with that cursory answer, she double-dips, asking Kagee what preparation and research he undertook for his role. “I didn’t do any research as I was writing it,” Kagee intones, “but when I was trying to map the story onto political events, there were certain sequences that needed to follow order, and so I needed to do some research using the internet and books and articles. I didn’t do a great deal of research,” he says, mentioning how the editor called him out for having a character smoke a brand of cigarettes that were only invented thirty years later.

A man in the audience asks Kagee if a course in creative writing would have changed how this book was written. Kagee replies that “when I wrote this book, it wasn’t for the purpose of writing a book – it was to entertain myself, to free-associate. And so, it kind of morphed in an unstructured fashion.” He compares his untutored and free-roaming manner of fashioning ideas and words into a narrative with the more formulaic notion of creating a narrative skeleton and then appending characters, relationships and ideas onto it. He invites Coovadia to comment. Coovadia proposes that “teaching creative writing is like running a country – the desire to do it is inherently disqualifying”. He quotes Freud in a delightfully throwaway fashion – “one of the burdens of being an adult is being forced to make sense all the time” – as he dismantles the tyranny of sense-making that goes on in the academy. “As anyone who has ever been in an academic department will know, a huge fraction of academic thought goes towards missing the point – not understanding the issue or evading the issue.”

The last question comes from a woman who asks Kagee whether he will write another work after this one. She expands her question to hear Coovadia’s thoughts on how his first novel influenced his future writing. Kagee answers, after an awkward pause, that another book is “not out of the question”. He expresses his honour at receiving the award, which he takes as an sign that he might not be completely rubbish at novel-writing. He mentions that there is a tension between his day job and the writing process: “I’m not actually being paid to do this – I’m being paid to write journal articles. If the balance is maintained,” he closes, “and I’m able to be a productive researcher, that’s fine. If it’s not possible to maintain that balance, then my day job has to trump creative writing.”

Coovadia’s answer is more liberated, more richly hued as befits the seasoned author. He suggests that there’s a ‘second-novel curse’ that tends to kill most novelists. Switching to the mimetic, he draws “a certain hedgehog-fox distinction”, wherein “the fox just does a whole bunch of stuff and is always hopping around doing different things, so if you’re a fox-type novelist, your second novel may not be related to what you’re doing in the first one. But if you’re a hedgehog – say, like Coetzee – you’ll always kind of be doing the same kind of novel: deeper and deeper, and then after a certain point, shallower and shallower.” The audience guffaws in shock at what they presume is a slight on Coetzee. Coovadia deadpans. He tries another metaphor, that of the farmer who rotates his crops between different fields, leaving one fallow for a while and then returning to it later. “These little tricks of perspective make you try new things, as an author.”

With these final remarks, the session closes and we adjourn next door for the usual cheesed this and glazed that. It’s an intellectually agile discussion in a way that more launches should be, and an excellent pairing of writerly talents on display.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

I was thinking more along the lines of a picnic in the Matobo hills! I couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery.

Organize a literary gathering and I shall take you up on that offer. I am nothing if not a seeker of sunshine…

Wamui, you are one cool dude. Why don’t you come and visit me in Bulawayo? The sun still shines here.