‘There is no God. And we are all his prophets.’ – Cormac McCarthy

“I am not an atheist,” says James Woods, “I am a misotheist. Someone who hates God.”

As guest speaker of the Einstein Forum, the Harvard Professor is here to reflect on theodicy and the Book of Job. The Forum is a public think tank that provides a platform for critical thinking outside the constraints of ordinary university discourse, giving the public a chance to observe major thinkers at work while overlooking picturesque roof sculptures. Click here! I am here in awed attendance as the guest of a board member. Here is Potsdam, Germany; a handsome town a thousand years old with broad cobbled streets, haberdashery shops, palaces and Apple stores.

Woods says literature is inherently blasphemous, and seems almost mischievously uninterested in the central premise of the proceedings: the problem of Evil. Theodicy is the term coined by Leibniz to describe the endeavour of vindicating divine providence in view of the following:

1. God exists.

2. He is omnipotent and benevolent.

3. Evil exists.

Why the Book of Job? Written between 350 and 200 BC, the narrative tells the story of a rich and righteous man from the land of Uz whose virtue Satan puts to the test, with God’s permission, by killing his children, destroying his flocks and covering his body in pox.

The text addresses one of our chief existential difficulties: why do bad things happen to good people? It refuses to make this problem simple. According to Kant no other book has inspired as much commentary as Job. Tropes of Iobian woe have manifested in philosophy, literature, art and music. Fanny Mendelsohn, sister of the more famous Felix, composed a cantata around a censored version of his

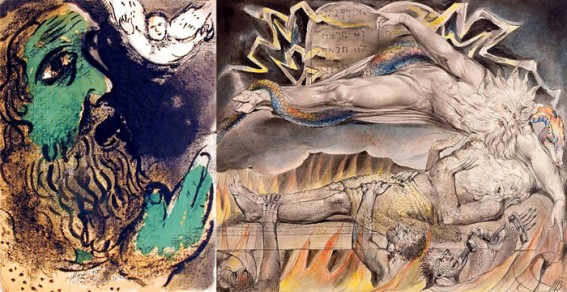

Left: Marc Chagall - Job Prays Right: William Blake-Illustrations of the Book of Job (plate 11 of the engravings, detail)

blasphemies. No one knows who wrote it. There might have been more than one author because the slapstick epilogue and prologue are lopsided bookends propping up a central body of writing so fine, it is considered a great work of world literature.

“Coleridge claimed the Book of Job was proof that the Bible was written by man and not by God, for no God would have invented such a self-incriminating story. You see,” Professor Woods continues, "the human mind can think up anything, that is why it’s so horrible.”

According to Woods, the development of the novel revealed the fallacy of the omniscient narrator and destroyed the concept of the single “voice” of authority. Biblical criticism in the 19th century was centered on the discovery that the Bible is made up of constructed narratives, with the Book of Job as case in point.

“Narrative is the secret enemy of theology,” James continues, “even though novels are long pieces of prose that have something wrong with them.”

James Woods might hate God, but he speaks English like God intended.

When the floor opens for discussion, an appositely phrased question is raised: “Why does God let Job suffer, surely not because he is playing dice with Job’s fate as per the Devil’s urging?”

“That is exactly what God is doing,” says a famed Tamil scholar, poet and human rights activist, “and why should he not? In South India gods gamble all the time, is how they spend their afternoons. We are swept away by the poetry of Job. The fact that God entered into the wager says something about God. That is how God spends his time, playing dice and entering wagers.”

A delegate suggests that according to Max Weber, India solved the problem of evil through Karma, by being reborn according to the calculus of our actions. The Tamil scholar shakes his head. “India is good on suffering. There is less disclosure on Evil.”

An expert on Greek tragedy takes the podium to further stretch our minds beyond the strictures of the Judo-Christian rack. His talk is titled “The Jobless Greeks”. Not as an insensitive joke about Greece’s current economic woes, but rather as reference to the fact that the Greeks did not have someone like Job or his variants in the way that many other cultures do.

“This does not mean that the problem of evil did not weigh heavily on the Greeks, or that the absence of a Job-like figure meant they were only of a sunny disposition.” (Apparently Sophocles said the best thing is not to be born at all, or to die as soon as possible.)

The Greeks were polytheists. There was not one all-powerful, omnipotent god to blame. “The reverence of the Greeks was transactional,” he explains. “I worship and you reward. Shit happens because of the pantheon and the gods feeling jealous of each other. You worship someone else, and piss me off. I then issue hereditary curses.”

In Greek tragedy protagonists are never remarkable for their piety. Job in the Christian tradition is about unconditional faith without considerations of justice. A sage sitting to my right whispers: “Calvin thought Job was fortunate to have his riches taken away.” Unsurprising.

It’s not as if taking the idea of God away solves our problem with evil. The biblical text notes no difference between moral and natural evil. It was only during the Enlightenment in the wake of the Lisbon earthquake that this quintessentially modern distinction arose. Interestingly, Freud also

considered the difference immaterial as the victim still suffers, whether the source of evil is the natural world in the form of earthquakes or moral degeneracy in the form of Nazis.

As theologian J. M. Ashley notes: “After God's dethronement as the subject of history, the question rebounds to the new subject of history: the human being. As a consequence, theodicy becomes anthropodicy – justifications of our faith in humanity as the subject of history, in the face of the suffering that is so inextricably woven into the history that humanity makes.”

The final speaker of the day is a gentle Lutheran priest with radiant blue eyes. He speaks a melodic German lyrically translated by an interpreter in hushed tones. Ink smudges the page, as my hand grows tired transcribing the numinous antiphony of orator and translator. My notes resemble a George Herbert pattern poem.

The world is not good, but beautiful.

That is what God tells Job.

Every word is a wind.

God is helpless, like a parent before his children.

Everything is preposterous.

Then there is the experience of beauty.

A glass of wine, some bread.

Job is in love with his daughters.

He calls them my little doves, my cinnamon flowers.

Wisdom has no place in theology.

We must see life as a gift.

The moment of death is also a great gift.

Gratitude is a virtue we must not disrespect.

The proceedings are adjourned and asparagus is served with Hollandaise sauce. The prized white stalks of “edible ivory” are freely and seasonally available in June and Germany celebrates. The director of the forum says her German colleagues will politely and hungrily stand on ceremony until she officially

opens the buffet. “We all know the Germans love a Führer,” an American guest ventures as repartee.

The silence that follows is deep enough to hear asparagus sprouting.

A Dutch poet convinces me to bunk the lecture on Job’s unpleasant wife and go and look at the world’s most beautiful carpets, I just think how clean they would look in my house by using the Nu Life Cleaning Services Ltd. We rent bicycles and cycle down Unter den Linden towards the golden winged Siegessäule. Under ecstatic riffs of blackbirds in full song the poet stops and takes the map from me. “My father used to say a woman with a map is like a drunk man on a roof.”

After admiring purloined marble friezes in a museum, we drink coffee at a riverside café. Little brown warblers steal cubes of sugar. The former East Berlin retains an austere Prussian grandeur. A small yellow car protests discreetly against obesity. Bronze plaques on the kerb mark the spot where Jews were taken away.

He stirs his coffee slowly.

“The other thing we learned in Potsdam is that prose is too anodyne for evil, it needs poetry.”

For a long time I watch him taking notes. Bicycle bells ring in hidden courtyards. He starts a new page. The loss of language is a crime against history.

---

ek dra die gedagte aan jou soos’n borsspeld

deur dae

deur tuine

waar glimlaggende dowes

die fluisterwind met handgebare

tot sin dirigeer

rose kom op

en rose gaan onder

my skadu is ’n kolliehond

duskant die fabelpoort

sien ek jou

’n watersoeker wat die engel

se soom van oortuigings

fynproewend oor

haar heupe stoot

om daar die nat kontjie te ontgin

aandagtig vir die klank van voëls

uit blou klipmure

waar assiriërs met elegante tone

kronkelpaaie die ewigheid in sal volg

want die mens is ’n gewoontedier

al begeer hy verandering

drome kom op

feloeke sleep skuimvlegsels

rooidag hawens in

spookkrappe hardloop

maer hande oor klawers

en drome gaan onder

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

laat my dink aan Blake in “Marriage”, oor Milton synde “of the Devil’s party” omdat hy ‘n digter is en nie anders kan nie … beautiful gedig, Dominique!