A friend warns me that as you approach forty, life only gets worse. And better. You look good, you feel good, but you lose interest in being nice and domestic. Your eyes begin to wander. In short, a recipe for growth and disaster.

I ponder her words as we taxi off the apron at Lanseria on an autumnal highveld morning. Two marriages and their baggage on board a silver Cirrus, call sign Mike Oscar Oscar, routing north. MOO for short. She is an elegant slip of American aeronautical engineering, tasked to carry us six thousand kilometres in six days. Up through Namibia to the Skeleton coast, past the Makgadigadi pans of Botswana to the Bazaruto archipelago in Mozambique.

“This is Mike Oscar Oscar, with four on board and four hours endurance. Requesting permission to head west.” What this means is we can fly as far as the Atlantic without dropping from the sky.

Our pilot is meticulous and excitable. And easy on the eye. He comments in melodic English on the landscape flowing past; its geology; history; the naming of things. Pigeons scatter above deserted farmsteads. Egrets fly in formation. He points up at a pair of cape vultures.

“Gyps coprotheres. You can’t really see it if you don’t know the name. Precise taxonomy reveals all. Don’t you agree?” I read somewhere that a certain Chinese encyclopaedia has different words for animals drawn with a fine camel’s hair brush, and animals that have just broken a flowerpot.

The plane climbs. Vultures are known to fold wings and drop when panicked.

We fly over the farm Brussels that once belonged to the pilot’s family. One of many. He speaks of its yellowwood floors and the dagga he and his brothers smoked all day instead of inspecting cattle. And frantically locking the shutters at night when the farm manager Piet came past with his pitbulls and guns, to coax them on springhare hunts.

The quilt of ploughed fields frays into the loose red strands of the Kalahari. This is the southern tip of a dune belt that stretches to the banks of the river Congo: A swathe of sand greater in reach than the Sahara. The shadow of a small plane shadows us.

We clear customs in Keetmanshoop. Koringkrieke are eating each other on the runway. Quiver trees line flowerbeds of rose pink quartz. Men in shorts and two-tone denim shirts are clearing guns, ready to hunt. The pace is as slow as a hallway clock on Sunday. We leave with stamped passports and a song in the heart.

“This is Mike Oscar Oscar turning out left to Wolwedans.”

We are met at the strip by Usko. When he speaks there is music in his words. He tells us that Wolwedans was once a farm, where lambs were taken from the kraal at night by hyenas and dragged up the Losberg. The farmer would watch them in resignation as they tore his livestock apart and say, “daar dans die wolwe al weer”.

MOO’s wheels sink into a quagmire. The pilot’s wife says we must not miss the sunset. Usko takes us to a dune of red silk sand covered in ostrich love grass. Along the way he points out the flora: Tsamma melons crushed by oryx, white shepherd tree roots that are ground for flour and coffee, slender-leaved lemoendoring wrapped in mistletoe.

A Southern pale chanting goshawk calls from a tall camel thorn, a flowering kokerboom full of dusky sunbirds, dainty Namaqua doves slipping past, sand grouse running ahead on the path. Mountains blistering and crumbling.

We watch the Southern Cross winking at twilight. It’s hard to believe this brooding, ancient and solitary place ever sustained a farm. That night I dream of the dead. This land draws the elemental from your subconscious. Like the sun draws water.

In the morning the pilot takes Usko for a flip. He says he will never forget us. We leave Wolwedans in awe.

We fly low. Fairy circles appear like dropped stones in a pond of grassland. An armada of red dunes sweeps inland while soaring mountains resist the advance of the wind. Sand finds a way and puts down vast, leonine paws gently onto Sossusvlei.

Below us are the loneliest farmsteads in the world. An oryx lifts his head at our passing. Dunes unfold. The sea feeds back on the land it has fed.

“What is the word for the desire you feel for another man’s wife? Count Almásy talks about it in The English Patient?” I ask over the intercom.

“Depends who is asking?” The pilot smiles.

“Me. The Afrikaans patient.” I smile back.

Walvisbay sweeps past, like a photographic plate of a World War II port, shrouded in mist. We swing inland away from the fog. Brandberg towers on the horizon. Life blushes in the arteries of remembered water. Namibia is a land of parsimony. And mountains. It yields gems.

“This is Mike Oscar Oscar. Speechless with joy. We are in the middle of fucking nowhere. Routing North.”

There is a psychosomatic illness, called Stendhal Syndrome, after the writer, which causes rapid heartbeat, euphoria and confusion. You get it from extremely beautiful works of art. The hospitals of Florence are full of swooning aesthetes. Namibia is as dangerous as the Uffizi; such is the surfeit of its natural beauty.

We descend into the pale valley of Puros. It is biblical in expanse. Makalani palms and camel thorn thread a dry riverbed. We are met by Gert Tsaobeb, a Nama from Sossusvlei. Employment is scarce, he says; he is happy to be up here in the North. He just needs to learn Herero. He’s been told its best to learn it on the pillow.

A photographer, South African-born and New Zealand-based, drinks whiskey with us straight from the bottle on the drive in from Puros. Originally trained as a gynaecologist, she takes a good picture. She knows things. About Stendhal Syndrome and the like.

Skeleton Coast camp crouches in the lee of a dune. We feel like scientists visiting a far-flung research base. The camp’s luxuries are appropriate to its context – two hours of lighting a day and warm water in a bucket.

The other visitors in camp are in fact scientists: a Swiss theoretical statistician looking for the elusive Higgs Boson particle, and her husband who designs tracks inside the Hadron Collider along which putative particles collide. They look as if Dr Seuss designed them. Exotically intelligent and gracious, they invite us to visit them at Cern.

I read in bed about Russian novelists who fretted that literature was irremediably vain, useless and immoral. I read further. Foucault made the point that the institution of authorship is largely dependent on the author’s liability to state punishment. Stalin handwrote the death sentences of Russia’s great writers, continuing in the vein of the Tsar who was Pushkin’s personal censor. There is nowhere in the world that literature has been taken more seriously than in Russia.

I lie awake wishing I had spent more time memorising the periodic table.

We wake early for an expedition into the Skeleton Coast National park. Gert drives us over the slope and slipface of the garnet sands. Pied crows, flagrant carrion feeders and opportunists, circle our tracks. We follow the footprints of a strand wolf. Flowering stones drink the morning fog, dune parsley sprawls with spicy leaves and ivory flowers, toktokkies bask on sand strewn with crystals, bleeding fingers come up after the rain.

Gert guides us away from sinking sand. We explore the derelict Sarusas amethyst mine. Workers lived here in abject igloos, now secured with Yale locks wrapped in plastic. Gert tells us that the South African owner was murdered.

“Hier,” says Gert, “kan enigiets gebeur.”

At last we come to the Atlantic. Cormorants fly slip above the jade surf. A whale spine lies unfleshed and supine on a shipwrecked caul.

“Southern rights”, says Gert, “Right because they were easy to kill. They swam slow and did not sink.” The coast repeats itself: driftwood, buoys, whale bones, diamonds. At Cape Frio jackals trot towards us, their curious faces wet with seal blood.

We swim in the cold rough surf. Gert makes coffee with Amarula cream. We sit on driftwood, drink “sterk koffie” and imagine Brazil across the sea. Gert holds a humble grip on a wealth of knowledge. He tells of wrecks and survivors and diamond thieves. The pilot promises to send Gert the story of Ernest Shackleton’s privations.

Our pilot remembers his grandmother’s hundredth birthday. Looking down on us from heaven, he toasts her: “Here’s to us. And those like us. Damn few. And they are all dead.”

The next morning we leave the Skeleton Coast before sunrise. We chase donkeys off the runway. Gert tells the pilot he landed on the district road. No matter. MOO is surrounded in the early morning by dragonflies. Vagrant emperors. Like us.

We leave Puros for Botswana. Angola is close enough to touch. We fly across the Caprivi where three counties meet in the way that governments like them to. Fences and border posts and straight lines.

We fly over the fecund swamps towards Jack’s camp in the Makgadigadi. These enormous saltpans are so flat and luminous, they bend the atmosphere and delusion sets in. Stone age tools are so plentiful that they are left in the veld as beautiful debris.

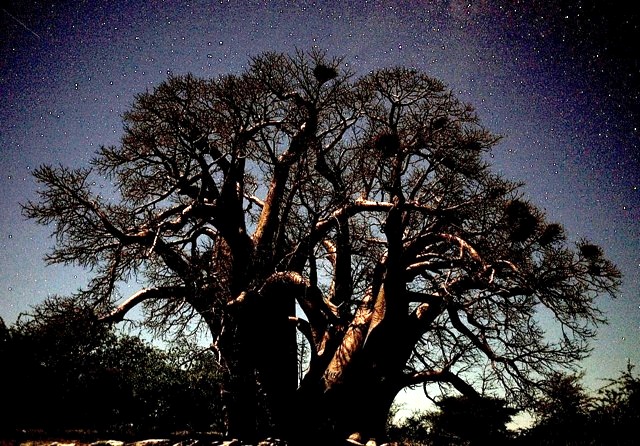

Jack’s son Ralph takes us to Thomas Pakenham’s favourite tree in Africa. Adansonia digitata. A baobab thought to be more than five thousand years old. It germinated when the Egyptians were building the pyramids. It was old when Jesus walked along the Via Dolorosa. It is a holy tree. A full moon rises.

In camp we look at photos of Ralph’s Ethiopian travels. The prison mountain of Gondar where the King banished all his sons; the carved stairs that fell away and left the building stranded as an eyrie; the walled city of Harrar, where hyenas are lured in at night through holes in the fortified walls to scavenge on rubbish.

We add chilli gin to our soup and listen to an American tourist tell her story of almost being eaten by a pride of eleven lions. Ralph says the fear in her eye is the truth. That story is real. We don’t stray from our rooms that night.

In the morning Ralph takes us to a clan of habituated meerkat. Sentries and matriarchs commune in a gurgling idiolect of panic and industry. Ralph says not to be fooled by this Sylvan scene – there is an intruder down in the den. He has mated with a female.

We wait. We christen the elusive cuckcolder Fred. Ralph predicts the exact order of events. Suddenly mayhem erupts. Fred makes a run for it and he is pursued by the entire pack. They eviscerate him, but leave him alive. It’s horrible.

“It is biological. Don’t betray the integrity of the family structure. There will be consequences,” Ralph continues. “Fred knew the risk he was taking.”

So what of my friend’s gnomic predictions about growth and disaster? Perhaps the recipe for growth is understanding that little in the having retains the charm it held in pursuit.

And disaster? Ask Fred.

Work Cited

2010. Elif Batuman. The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People who Read Them. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Dom! An insanely evocative piece of writing! Good enough to eat…

Well done. Give us more!

This is beautiful Dom. Really lovely. More, more …

Oh please write some more, this is beautiful. Tell us the rest…

I found this riveting. Take it through to Mocambique. And am wondering, was Fred a Russian novelist.

Dom, This so beautiful. Articulating what the rest of us simply cannot.