Launch of Call and Response by Cedric Nunn, 12 June 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

WAMUWI MBAO

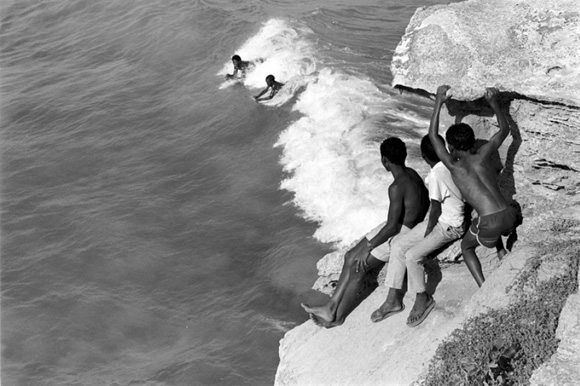

The idea that we must pay particular attention to the ordinary – an ostinato captured aphoristically by Njabulo Ndebele two decades ago, has an enduring currency. The photography of Cedric Nunn attends to the task of making visible the ordinary in all its intricacy and richness. For the last three decades, Nunn, who began working professionally in the heavily charged atmosphere of 1980s South Africa, has been immersed in the process of documenting the warp and woof of daily life for those who live in South Africa. Nunn’s often haunting work has always sought to capture the resonances and textures of daily life for the downtrodden and the destitute. His work carries a political dimension, to be sure, but that dimension is woven through the fabric of social life in ways that displace the strident and the pessimistic in favour of the quietly hopeful.

Nunn is launching his new collection, Call and Response. This publication takes the shape of a mid-career retrospective, shaping the trajectory of his work from its early beginnings to the present day. It was for this purpose that he was found on Tuesday 12 June at the Book Lounge. He was in conversation with Patricia Hayes, who is a Professor of History at the University of the Western Cape. Hayes introduced Nunn as a photographer who has been to the quiet places, the places we don’t often go to. She spoke of the way in which his pictures “reconnect with the wholeness that people still have” in the face of adversity. Hayes underscores the magnitude of Nunn’s effort in putting together Call and Response, pointing to the intense symbolism Nunn brings to each perspective his camera captures.

Hayes is an able interlocutor, and her conversation with Nunn takes the form, mirabile dictu, of a call and response. She begins by singling out the introduction to the work as “extremely personal”, an intense meditation on “the ways families became unstitched, as groups of people were forcibly torn apart during Apartheid". Recalling that Nunn was born and grew up in Natal, Hayes elucidates on the way “families that were designated as Coloured were moved to make way for the homeland of Kwazulu". She tells us that she sees the first part of the book as “a meditation on certain kinds of loss” referencing Nunn’s repeated use of captions that emphasise how no traces were left after the forced clearings. Hayes remarks on the difficulty of connecting the private and public, the personal and the political, with Nunn’s images of his extended family moving between the two poles, connecting them and redefining them in new ways. She speaks of how Nunn’s images highlight a sense of connection that remains in the midst of the breaking down of physical structures and the physical dispossessions that were underway.

Nunn’s response is that for himself and the photographers he has worked with throughout the years, there is a sense of the personal and the political being intertwined or linked in what he calls “a feedback loop”. Nunn notes that he had an intuitive sense of the link between the personal and the political, but that these early images represent a process of honing, a “working towards” representation. He describes the personal dimension of his work as arising out of “necessity in the face of limited resources”. Photography was in those days “a crazy calling” for Nunn,

a desire to respond through images to the situation at hand, to go out and be part of a field where there was little hope of any pecuniary reward or income. Nunn situates himself in the generation of photographers who came after Dennis Goldblatt, and he gives praise to the famous Omar Badsha who sits in front of me and takes multiple pictures of the conversationalists. These photographers, Nunn avers, looked at the personal and made interventions that reflected on a much larger scale.

Images travel through space and time along different lanes of circulation, and here Hayes remarks that “photography is a double-edged art”. She recalls how images by photographers like Cedric were distributed in the eighties on a global scale, often with the captions removed. “There’s a kind of genericisation,” she says, “which I think speaks to the label of the struggle photographer . . . and in that way it remains a rather superficial exercise because those images get read in particular ways and according to certain lines of expectation.”

The book in question, which Hayes holds up for our approval, is of the wide and glassy-sheened sort that best show off the arresting images contained within. Hayes speaks of how these photos capture a certain introspectiveness, and asks Nunn whether introspection is the natural gift of the photographer. It’s a question Nunn has some trouble answering and I get the sense that, like all magicians, he has trouble revealing the tricks of his trade. “Photographers are always saying that they don’t have words, but that’s nonsense,” Hayes quips. “I don’t think a lot of photographers get the introspection thing,” Nunn offers, citing the enormous pressures professional photographers are under to make each deadline. “It’s very difficult for photographers who’re working in a newsroom to be introspective about anything other than how to get the next angle," he continues. He finishes by proposing that “if you’re true to the nature of the medium . . . a medium that is by its nature arrested, it allows you to return to it, to meditate on it, to reflect on it, to be moved by it, to be transformed by it”. Nunn speaks of the ability, always tenuous, of the photograph to induce thoughtfulness in its viewer, a sort of possession that “doesn’t always happen".

Nunn’s words bring forth the experience of the uncanny one bears witness to in his shots. He talks of how revisiting his works for the retrospective has been a similarly unsettling experience of introspection for him, one that has allowed him to reflect on his current work in new ways. In this regard, it is a looking forward to the future as much as it is a look backwards towards the past. “If we are to learn from things, we have to revisit them and restudy it...we are in danger, constantly in danger of history repeating itself”, he ends. His tone in responding to Hayes suggests a self-reflexive thinking-through that belies the all-surface visage of his medium.

Hayes reflects on how the way in which Nunn’s work reverberates with his family history allows us to perceive a much longer trajectory than we otherwise would if we simply look at Nunn as a “Struggle Photographer”. His work, as Patricia avers, scripts a family history that stretches back into the 19th century. Hayes puts it to Nunn that the history his work shows, a history of building and being pulled apart, of destruction and regeneration, displaces the sort of optic that views South Africa only within terms of the ruptures it has undergone in the last thirty years. “We need to take a much longer view of things”, Hayes asserts.

Nunn speaks of the limitations of being a Struggle photographer, referencing the difficulty he and other photographers experienced in evolving or transforming under the changing times. “I realised that if we wanted to transform the way we represented ourselves . . . then we needed to birth a whole new generation of people who would be involved in that process.” Rather than taking up the cudgel of career-driven and market-related commercial photography, Nunn chose to share his knowledge with the young and the aspirant, fielding a series of workshops and training academies.

Hayes' final point – an hour is barely enough time for this conversation to occur – is that she is struck very forcibly by what she sees in Nunn’s book as “a tremendous sensitivity . . .to not only try to document what is happening in people’s lives but to also bring out the really unique spaces which people have inhabited even when they were very poor”. She references an earlier interview with Nunn where he mentioned that he grew up in a world without art, a visually starved world. In Nunn’s work, she sees attentiveness to the visual cultures people enact in these spaces of attrition and poverty. Nunn describes his family as having “an organic sense of the visual”, and suggests that “art is potentially everywhere and within most people”. He sees his work as a move away from the idea that art needs to take place in some rarefied realm, towards a more communal understanding of how art functions. “The world we live in,” he says, “now recognises that we give away our power when we ignore the political.”

The questions that follow are brief, and somewhat scattered. George Hallett, another of the photographers in the audience, racks Nunn for answers about the inspiration for one of his more famous pictures, and Nunn tries out several replies before ascribing it simply to “magic”. On that eccentric note, and with the usual nod to the people who keep these events in vino, the event was done.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project