Launch of The Cambridge History of South African Literature edited by David Attwell and Derek Attridge, 13 March 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town

WAMUWI MBAO

Go to bottom for an audio podcast of this event.

It’s a sun-filled day in Cape Town and the Book Lounge on Buitenkant street is overflowing with literary academics, readers at large and the various other clever people of higher literary criticism who meet to sip wine and discuss the literary. It’s an auspicious occasion, a prestigious book launch, and the event is given complimentary placing on the Book Lounge’s glossy upper level rather than languishing in the rather badger-esque basement. All have drawn near for the unveiling of the Cambridge History of South African Literature, a capacious collection of essays brought together under the editorial curatorship of David Attwell and Derek Attridge. Both these prominent professors of literature from York University are in attendance to give a few words, shake a few hands, and give over their well-nursed project to the world. As they take their places on the slightly raised dais, they are joined by Njabulo S. Ndebele. The assembled crowd is by this point spilling out of the doors, the murmur of flaccidly awkward social chit-chat a sort of academic white noise punctuated by the clink of wine glasses and the crunch of breaded hors d’oeuvres. Andre Brink is sitting quietly in front of me, waiting for the event to begin.

David Attwell

David Attwell speaks first. The venerable Attwell thanks Cambridge University Press for providing a home for the project. He gives a purposive précis of the individual contributors, drawing our attention to those, like Mbongiseni Buthelezi and Meg Samuelson, who happen to be in attendance. There’s a healthy attendance from the contributors, and Attwell hails the standard of the authors and their contributions. In particular, he singles out Chris Swanepoel, who solved the difficulty the editors had with finding a writer for the (dubiously broad in title) chapter, “Writing and publication in African languages since 1948”. Others named are Malvern Van Wyk Smith, Daniel Roux and Louise Viljoen.

In Attwell’s words, the book is a “massive undertaking”, an attempt “to provide as full and as generous an account of South Africa’s literary capital as possible.” He speaks about how he sees the work as a multivocal literary history, one which is “both outward-facing and inward-facing” in its reach. His talk is replete with these flippantly academic phrases, but the audience is sown with enough of the academically-involved, who absorb the quiddity of what is being said and greet every anecdote with the peculiar stifled guffaw-laugh often heard at these gatherings. He tells us that he thinks of the book as “a Hadron Collider”, to a titter of laughter from the audience. “What we’re trying to do,” Attwell continues, “is crash traditions into one another to see what Higgs boson or God particles disperse from the interaction. We don’t actually identify these God particles, but we hope that our readers, as they experience the contiguity of these languages and the traditions, will take our project further and flesh out the implications of this multilingual literary history.”

Attwell shows he has a well-tuned ear for the local, relating his and Attridge’s happiness at being able to convince Cambridge University Press to publish a soft-cover version of the tome, at a reduced price. This is no small consideration, since the average academic isn’t blessed with Trimalchian pockets. Suitably enriched with this information, our attention turns next to Derek Attridge, the next speaker.

Derek Attridge, Njabulo Ndebele and David Attwell

Attridge speaks about the genesis of the book at some length, citing April of 2006 as the start of conversations on the project between himself and Attwell. He too thanks Cambridge University Press for their assistance in bringing the idea to fruition, and recounts a workshop in 2008 where twenty-five of the collection’s contributors met and discussed how the anthology might be written; out of this creative melting pot came the project proper, which was then smelted over a number of months into the purple tome before us today.

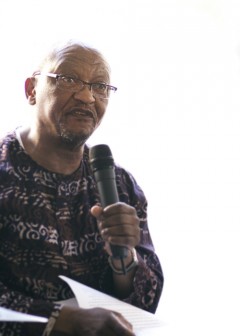

While Attridge is saying this, there are one or two members of the audience paging through the book, bounteous copies of which are piled near the speakers. Attridge’s main role is to introduce Njabulo Ndebele, and he does this after a while. Ndebele has assumed a quiet position as one of the pre-eminent elder statesmen of the literary scene. Always a writer of great consequence, he has gained a newer prominence of late as a cultural commentator and public intellectual. He kicks off his reflections on the state of South African literary culture with an anecdote about his enthusiasm for the Kindle as a device which has revolutionised his reading practices. However, the tome he held before him, he told the audience, reminded him of what he loved most about paper books. The book’s “fond heaviness”, he said, gives a sense of the human intellectual work that went into it, “the sheer weight of extraordinary human effort.”

From his years as vice-chancellor at UCT, Ndebele has gained the valuable skill of unravelling metres of delightful intellectual babble before adoring crowds, and he is one of the few sophisticated writers today who needs no sophisticated response from his audience. He has the ability to convert the dismaying impenetrability of the literary into speakable bon-bons that the scholarly and untutored among the audience respond to with equal pleasure. As he speaks, the audience takes on the tenor of a religious congregation, its rapt attention steadied by nodding heads and chortles of agreement every time Ndebele unwraps a belletristic point.

The meat of his talk is about how the politics of memory have played out in South Africa. Describing the historical contestation between parties as one marked by negotiations, Ndebele says that “the terrain of this book is about how the conquerors and the conquered have lived together over three centuries of fateful interaction”. He complicates the binary he has set up, reminding us that among the conquered themselves, there existed conquerors. He explains this idea as one of many “hidden fissures” that erupt from time to time across the structures of humanity in South Africa. The conquered, says Ndebele, “begin to construct archives of memory from which they record reason they have to keep resisting”, bringing to mind the struggle songs employed so powerfully by the liberation movements of South Africa.

Njabulo Ndebele

Ndebele’s portion of the launch brings delight because it follows the path established by the other two, but it opens up a greatly deeper conversance around the meaning of an anthology on South African literature, which is of course an anthology on South African identities. He discusses South Africa’s history as one of “things experienced differently, but nevertheless shared in some ways”. He further emphasises that the story of that sharing is one that itself has not been shared, and stresses his belief that it must be opened up, as this book does, if we are to develop a greater understanding of ourselves and our positioning in the world.

In the remaining twenty minutes, he touches on various topics including the need to rebuild our intellectual capital in the wake of divisive elements, the role of the public intellectual, and why we need to strongly contest the new and unwelcome definitions freedom is acquiring in this age of uncertainty. His words send bubbles of approval through the crowd, and provide a fitting welcome into the world for this collection of essays. Questions are deferred in favour of a more informal post-talk mingling, and the academic bread-and-circuses routine begins once more.

Cambridge History of SA Literature book launch by SLIPNET

Njabulo Ndebele and David Attwell

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project