Report on Satire and the limits of freedom of expression, with Sandile Memela (chair), Glenda Daniels, Diane Victor, Chris Wadman and Zapiro.

Session 5 of the Mail & Guardian Literary Festival, Saturday 1 September, Market Theatre.

KARL VAN WYK

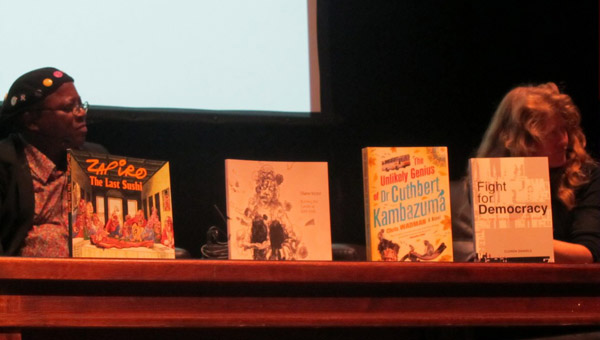

Sandile Memela and Diane Victor behind the fortifications of new books by the panelists

After coming out of a panel discussion on satire and freedom of expression in South Africa, I skulk away to a quiet couch amidst the hubbub of the Mail and Guardian Literary Festival at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre. Tsogofatso, a girl of about eight, keeps me company as I type away to the sound of her pencils scribbling on her colouring book, periodically sipping at her McDonald’s drink. While we serenely work in our shared cocoon, one of the event’s organisers, Darryl Accone, runs around making sure the twelve sessions that make up the festival run smoothly. A few hours ago, he began session five, on satire and the limits of expression, with an apology for the session’s fifteen-minute delay, after which he introduced the panel, chaired by Sandile Mamela and featuring an interesting mix of contributors: Jonathan “Zapiro” Shapiro, whose courageous cartoons have made him equal parts commentator and, to the dismay of the targets of his satire, political rabble-rouser; academic and journalist Glenda Daniels; renowned South African artist Diane Victor; and fledgling novelist Chris Wadman, author of The Unlikely Genius of Dr Cuthbert Kambazuma.

Chris Wadman, author of debut work The Unlikely Genius of Dr Cuthbert Kambazuma

Mamela begins the discussion by asking Daniels about whether or not freedom of expression is under threat in the country. He prefaces his question by referring to Daniels’s book, Fight for Democracy: The ANC and the Media in South Africa, in which she claims that South Africa is one of the freest societies in Africa. Daniels responds to the question emphatically in the affirmative, referencing the disputed Secrecy Bill. Seemingly building up to the media’s supposed insensitivities to government, Mamela then asks if the media should be held accountable for its actions, to which Daniels, moderately perturbed by the question, responds by saying that, in her experience, the media is “accountable and professional”.

Chairperson Sandile Mamela probes the panel on the press's accountability for its actions

Turning to perhaps the most well-known member of the panel, Zapiro, Mamela begins by asking him about Zuma’s R5-million case against the artist for his (in)famous depiction of the then-deputy president as a man with his pants undone, about to rape Lady Justice. Zapiro, with the majority of the audience clearly on his side, claims that the accusations made by Zuma against him are baseless, and that the ANC has a tendency to read metaphor as fact.

Mamela then moves on to what he calls Zapiro’s “Dick Cartoon”, in which he portrays Zuma as, well, a dick, and he asks Zapiro to comment on accusations that he is either a racist, or culturally insensitive, especially when the cartoonist references the president’s dozens of children (some of whom were born out of wedlock), his mistresses, and his wives. Zapiro claims that he is none of these things and explains that it is an artist’s duty to “push those buttons” when public leaders are acting in ways that can be considered homophobic, racist, sexist, and so forth. Further, as Zapiro says, given Zuma’s almost self-promoting sexual history, the president comes close to presenting himself as a “phallic figure”. Zapiro further suggests that his metaphorical depictions of Zuma largely speak the truth.

Zapiro doodles as Glenda Daniels counters Sandile Memela, insisting the media is generally accountable

Turning to the artist of the panel, Diane Victor, Mamela asks her about her method when approaching dire social problems. Victor considers her response. She comes across as intensely insular as she observes the chairperson through beady eyes, hidden behind a mane of blonde hair. Victor’s bold and often quite dark images suggest that her art speaks louder than she does, and her response to Mamela’s question brings some illumination to her work. “I make images … for myself,” Victor says, adding, in the same breath, that she is better able to articulate herself on pressing national issues through her art – she is primarily a visual commentator. Later in the discussion, responding to a question from the audience about whether or not media and artists have limits, Victor calmly thinks about this and says there should not be any external limiting of expression, and that limits should be self-imposed – artists should police themselves.

A somewhat inscrutable Diane Victor gently suggests that artists should police themselves

Mamela then turns his attention to the only novelist on the panel, Chris Wadman, characterising him as a truly Africanised white man – here Mamela is referring to Wadman’s journeys across the continent to areas like Zimbabwe, where the writer spent his formative years, Nigeria, Kenya, and elsewhere. Using this as the basis for his question, Mamela asks Wadman about the state of freedom of speech on the continent and whether or not South Africa is truly a free state. Wadman seems to confirm claims made by Mamela at the beginning of the session, in which Mamela hinted that South Africa was perhaps the most liberated African nation on the freedom of expression score. However, Wadman argues that such freedom must continuously be guarded – its loss will bring about undesired consequences.

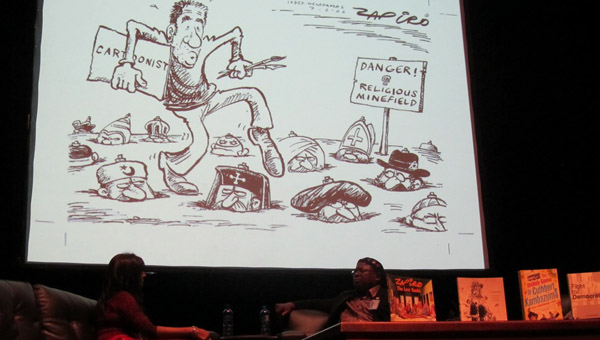

Panelist Glenda Daniels and chair Sandile Memela sit rapt as Zapiro talks the audience through his cartoons

Breaking away from the talking-heads format of the sessions, Zapiro then provides the audience with a presentation of some of his cartoons, illustrating his claim that he unapologetically pokes fun at racists, tyrants, homophobes, and hypocrites, both local and international. The audience responds well to this presentation, splitting their sides as Zapiro gave us samples of his sharp wit and fine sense of irony.

The most interesting question from the audience was the observation that irony and satire break down societal structures for the sake of progress. The panel largely agreed with this, with Daniels stating that it is the role of satire to “[build] democracy”, and that “it’s about development”.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project