Launch of Solace by Andrew Brown, 8 May 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

LUCY GRAHAM

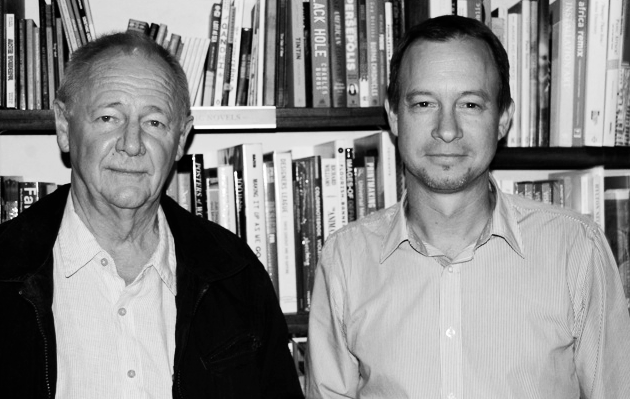

Andrew Brown (Photo by Liesl Jobson, Books LIVE)

By the time Andrew Brown is seated on the small podium, along with Michiel Heyns, who will interview Brown on his latest novel, Solace, The Book Lounge is full to overflowing. The buzz in the room, I notice, is peculiar to the launch of crime fiction novels. It was the same vibe at the launch of recent novels by Deon Meyer and Margie Orford. Say what you like about South African crime fiction as a genre, but there is no denying its burgeoning readership and the interest – even now among academics – that it is garnering.

One of the points made by Leon de Kock and I at a conference entitled “Crime and its fictions in Africa” at Yale University in April this year was that crime fiction may not be “the new political novel”, but it does attempt to operate as “a diagnostic machine” for the problems of contemporary South Africa. Also that, in a context where we may ask “what is left of the left?”, crime fiction harnesses the energy of the underworld, of the city’s underbelly, possibly replacing the role of the political novel, which was concerned with a political “underground”.

The conversation between Heyns and Brown begins with a discussion of writing. As Heyns points out, Brown is an advocate, the father of three children and a police reservist, so “when does he find the time to write?”, Heyns asks. Brown’s answer is surprisingly non-grandiose: he regards his writing as “a hobby”, as something he does in the midst of life, while the children are making a noise and the “bergie” is knocking on the door, and the dinner

Michiel Heyns and Andrew Brown (Photo by Liesl Jobson, Books LIVE)

table is being set. This is not only humility, however, he suggests, it is a useful strategy. Not taking himself so seriously enables him to face up to the empty page, to the anxiety that after writing one novel of 80 000 words he will not be able to produce another. Since this is now his third novel, one suspects that his strategy for writing works. In his conversation with Heyns, Brown also thanks his editor, Lynda Gylfillan, who is in the audience, for all the hard work she put down on the text.

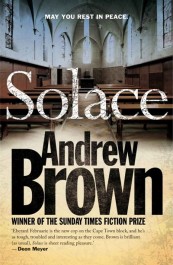

As Heyns suggests, the titles of Brown’s previous novels, Cold Sleep Lullaby and Refuge, like Solace, seem to offer something comforting – but the question is “from what?”, so there is a sinister undertone despite the offer of comfort. Even the heading above the title of Solace “May you rest in peace” has a chilling effect. And all three novels are in fact blacker than pitch in mood and subject, noir and “hard-boiled” enough to measure up to the

best. As evidence of this, Brown reads a passage from the novel describing police Inspector Eberard Februarie waking up with a deadening hangover on a bleak morning with rain or grit beating on grimy window panes.

His previous novel, Refuge, Brown claims, came out of his anger towards a middle-class that was seemingly indifferent to South Africa’s problems, to the plight of the less fortunate, and much of this novel focuses on middle class lives. But the Cape Town of Solace, as Heyns points out, is definitely not one of “leafy suburbs”. Rather, we are taken into the deep underworld of the city.

This is an intertextual underworld, however, one where the characters of other South African novelists are “fair game”. As a member of the audience points out in question time, the novel references characters in the novels of Meyer and Orford. Orford’s Riedwaan Faizel is mentioned as “the duty detective”, and Brown’s detective, Eberhard Februarie, refers disdainfully to Faizel’s relationship with “that Hart woman”. Meyer’s Captain Benny Griesel, is referenced by Februarie as “an example to him, to many of them, proof that a man could beat his demons” (Solace, 18).

The novel is also, importantly, an exploration of religion, of the three monotheisms of the city, and of the world at large, linking the local to the global. The crime scene is a synagogue in Sea Point, where the body of a young boy is found mutilated, in what appears to be a ritual murder.

As a self-proclaimed atheist, a converted Jew (who claims to have a deep respect for the cultural traditions of Judaism), and, in his own words, “an old ANC hack”, Brown is well-positioned to write a novel about religion and politics. He comes across as sensitive to the problems and complexities of religion and so-called religious tolerance. The word “tolerance”, he points out, is questionable as it always already evokes the image of intolerance, of someone with a stone in their hand, about to throw it, but restraining themselves. He mentions how France’s banning of the headscarf for Muslim women left him with deeply ambivalent feelings, despite his position as an atheist and his issues with Islamic fundamentalism.

In his novel, Brown has tried to remain sympathetic to religion, but as a Rabbi in his novel states, don’t come to religion for answers, for solutions to earthly problems.

Like other recent South African crime novels, Solace suggests that it is rather to the crime novel itself that we should turn for answers, for a diagnosis of society’s ills, even as these answers will be constrained by genre.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Great piece, Ms Lucy. Only wish this novel was available in hardback in the USA. I work consistently on nurturing a readership for contemporary South African crime fiction in my libraries for just the reasons you mention – commentary on current SA society – but this title seems to only be available in US on Kindle. That limits me. Hope I am wrong and the author’s works will be made available to the broader US market.