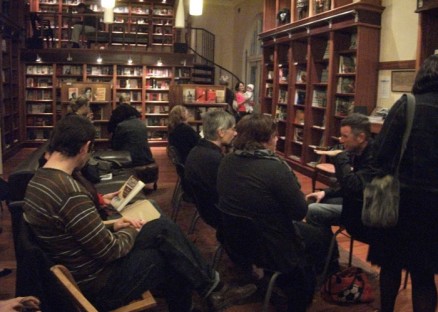

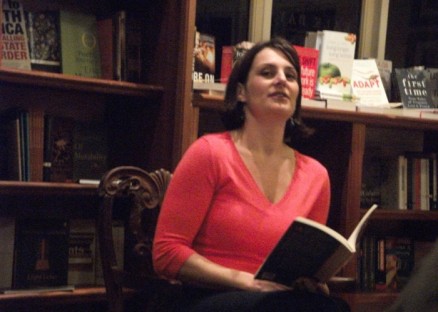

Launch of Diane Awerbuck’s short story collection, Cabin Fever, Friday 8 July, Kalk Bay Books, Cape Town.

LEILA BLOCH

“People read for lots of reasons," says Diane Awerbuck to her interviewer, Henrietta Rose-Innes. “It can be nourishing, in a non-threatening way.”

Awerbuck was talking at the launch of her new collection of stories, Cabin Fever.

- Waiting for Diane

Since the success of her first novel, Gardening at Night, there have been a few distractions: children, a “soundly rejected novel”, the complexity of writing itself; but all that has led up to a hybridised, accessible, highly skilful and arguably “unique” collection of short stories.

Awerbuck’s daughter rests on her mother’s lap for most of the interview, her interjections welcomed; it is an intimate, conversational evening. Positioned in a maelstrom of fierce, female, South African voices, the two women are simultaneously critical and affirming of one another’s work. Rose-Innes is supportive but unafraid to probe into what lies behind the creation of this collection – the art of finding inspiration, the craft of writing as well as understanding core literary debates.

- Henrietta Rose-Innes and Diane Awerbuck in conversation

“New South African writers are annoying,” says Awerbuck. She’s not concerned with arguments over who owns what narrative, for example: “Who owns the seminal township experience”, who is "authentic", or suffering the most. These concerns do not add anything new. There are ways, she reassures the audience, that one can say something old in a new manner without focusing on who has the right to tell each story. There’s a surplus of accessible narrative. “South Africa is rich in things that haven’t been mined,” she reflects. “It sounds a bit like shell: Let’s frack that, shall we?” Myths, for example, are “an easy way to twiddle old lives with new ideas”, and many of them inform her writing.

Rose-Innes does not shy away from describing Awerbuck’s stories, which play with the supernatural, myths and legends, as “magical”. Some are “completely terrifying and some of them are enchanting”. In response, Awerbuck mentions Mami Wata, an African goddess, half human and half fish, who features in her fiction. “The reason I’m interested in her is that she’s got the kind of revenge you wish you had, or at least I do,” she continues. Awerbuck illuminates how archetypal imagery can contain and transform experience: “Archetypes translate hopes and wishes into another dimension.”

What gives Awerbuck's work “energy”, says Rose-Innes, is the effect of hybridising. She asks Awerbuck how she goes about “blurring the division between fiction, history and actuality”. Many of her stories come from recent news, extracting dialogue from articles in direct speech. “We have so much input,” Awerbuck muses. Awerbuck undeniably has an unusual hybrid of influences, both real and fictional, and her borrowings are considered and skilfully crafted into her work.

- Awerbuck reads “Splodge gets Married”

The mythological and psychological in Awerbuck’s fiction are often challenging and heavy, and Rose-Innes wonders whether her PhD in Trauma fed into her fiction. Awerbuck is “interested in what people do when they are young and desperate, when they do things they can’t come back from, with no room for excuses”, because after committing a crime life goes on. Maybe that’s why people read, to find patterns, suggests Rose-Innes - it's a means of ordering one's experience.

Awerbuck feels that having a traumatic experience isn’t the defining thing, but moving into narrative may be, without discounting the importance of therapy. She does not see narrative as pure catharsis but stresses the importance of working through things, otherwise you remain stuck in the past.

Awerbuck is carving a path in fiction with a bold and empathetic voice that looks at content in a new way. The shelves of Kalk Bay Books are filled with female writers whose style contrats with hers. Sarah Lotz’s The Mall offers a racing postmodern adventure into the heart of consumerism, a form of "Pulp" literature. Finuala Dowling offers psychological realism in Homemaking for the Down at Heart in which she imbues the commonplace and domestic with character-driven narrative. Awerbuck refers to Rose-Innes’s collection of stories, Homing, as the “Great Gatsby for the 21st century”.

A unique voice is something writers desire, what new writers are in search of. In the light of V.S. Naipaul's recent stab at female writers, claiming they could never write as well as he does, there is certainly a wealth of women talent in South Africa, each with multidimensional perspectives. Awerbuck’s next novel is due out in 2012. Also from a woman’s perspective, the subject matter is a well-known South African fixation, Saartjie Baartman, and the novel focuses on the importance of finding “the voice for the voiceless”.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project