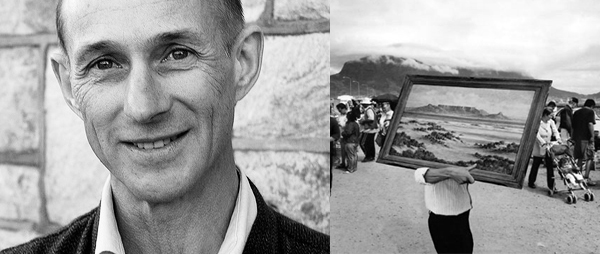

Few scholars or poets have done as much for English literature in South Africa as Stephen Watson. Commenting on Watson’s collection of poems, The Other City, J.M. Coetzee writes: “Whether writing about the loves of men and women or about walking under the African stars, Stephen Watson is a better poet than his time (the expiring end of the twentieth century) and his place (squalid, beautiful Cape Town) deserve.” Whether we deserved him or not, Watson’s writing emerges as a rare moment of clarity in this windy peninsula of Cape Town. Looking through the obituaries written after Watson’s death, one is struck by the frequency with which the word “generous” appears. And what should a poet be, if not generous? Is there such a thing as stingy poetry? Watson’s legacy to South African literature must be considered in light of the fact that he was, first and foremost, a poet – a lover of words. His development as a writer was shaped by what he referred to as a “ ... faith which is implicit in the act of creation itself.” And his writing attests to this, prose and poetry, which both resonate with that generosity that comes from years devoted to language and a faith in the written word’s ability to bring the human out of the human.

Watson’s career and legacy have come to exemplify this faith in and dedication to that other possibility of language, which gives life to the written word and makes new meanings available. In an interview with Susan Gardner in 1984 he said that:

real writing begins where ideology ends, in that silence on the far side of it, where, for whatever reason, the structures provided by an ideology prove no longer adequate to the nature of our experience ... Real writing does attest to the fact that we are not totally entwined in the tentacles of an ideology, as some theorists would have it. Implicitly, it provides us with one of the best arguments we have in support of the belief that, however constrained we might be, however monolithic the controls over our lives might appear to be, we nevertheless do possess a margin of freedom which is inalienable. Any real creativity attests to this. In my view, it is one of the chief tasks of writing to reveal the inadequacy of ideology, any ideology. The end of art, according to my view, is the defeat of ideology and ideological thinking.

Watson takes the jargon of ideology as the antithesis of poetry – a dead language, within which there is no space for new meanings. And in his essay “The Rhetoric of Violence in South African Poetry” he argues that the writers of the late apartheid era were “obsessed with the twin coordinates of politics and history, forgetting that whatever the legitimacy, even necessity, of our fascination with these, if we are oblivious to another dimension, another space, we are most likely to fail as poets – and as something more than poets.” For Watson, the space of poetry is a space in which language can breathe, shape itself. Our poetry can be seen as a barometer that measures the health of our language, which, in turn, tells us about our health as a society.

If this is the case, then the poetry emerging now, twenty years into a democratic South Africa, reveals some worrying symptoms, suggesting that there may be reason to question our “linguistic well-being.” A case in point is the 2011 “anthology” of “South African” poetry, We Are. While there is some good work in it, any visitor to South Africa, picking it up in Exclusive Books, would probably come away with the sense that we were a puerile nation, whose poetic fecundity stretched little further than a teenage aversion to proper punctuation. Aryan Kaganof offers us this poem, called “the rainbow homeless (reprise)”:

like a volcanic eruption

the word sperm spurted

out of my texticles

the muse lapped it up

out of my flowing cup

of overpoems

stones poet inna melville

waiting for subject matter

to sink the black in

offering

a sacrifice

to the gods of wordy

rappinghood

i’m not a homeboy

i’m a manotour

mina ngi ngu ngamla

what does it mean?

whitey

is it really what you see

or merely a projection

of my lack of melanin

multiplied by the angle

at which light waves

caress this skin

i’m breathing in

these light waves which are also particles

at the same time

just like a lover’s perfume

that is both heaven and the beginning again

of your dissolution

merely turning round isn’t a revolution

neither is a government

of black gnats on a golf course

while the indigent

remain the major residents

of the land lack

which was from them taken

but never given back

despite the voting

and other elaborate forms

of time wasting

Lines like these show a kind of opening, a poetic blind spot that sparks concern. This verbal blindness renders the logic of the poem meaningless, as the poem is overshadowed by a larger question: Does this language offer language any breathing space? I would argue that poems like this are adding to the clamour of history, rather than operating in the above-mentioned fashion of poetry. In “The Rhetoric of Violence in South African Poetry” Watson quotes Andrei Sinyavsky: “Words must not shout. Words must be silent.” And goes on to say that: “... so far from being history’s minion, poetry is actually its antagonist. Pre-eminently so; modally so. It is in this art’s capacity to call to question, even refute, the historical, existential, and linguistic orders that there is to be found the root of its spiritual power.” A poem like this only responds mimetically to the pressures of the time, from within the historical and linguistic orders, offering nothing of itself to the reader.

But the problem is not in the poetry; it is in the trend. Predictably, we are generally more concerned with histrionics and bombast in our popular English poetry than ever before. That which is locally classified as “South African” poetry seems to have as a prerequisite the failing of poetic language and a reversion to ideological terms. And, more worryingly, those poets who are attempting to write in that other mode of writing, which speaks of silence and nurtures some sanity in our language, are being written out of the tradition. If one is not willing to write poetry that is overtly political, one is at risk of being left out of the group called “South African poets.”

It must be clear by now that my concern is that Stephen Watson should not be written out of this group, but be seen as a leading figure. Watson most certainly stands within the small circle of South African English writers who breathed life into our language, a poet dedicated to silence, resonating above (or is it beneath?) the clamour of ideologies. He was, through a turbulent time in South African history, a writer who kept his finger on the pulse of South Africa’s English literature, poetry in particular. He gave us images that stand outside of the clamour of history that surrounded him. This is taken from “North-West Cape, 1985,” a poem published in his 1988 collection, In This City:

Even now what bitterness is in the bushes, dry as old tobacco;

what bitterness in the camps of stone; and how much more today

in that man tramping, sockless, wind rifling his trouser-leg,

in that man seen labouring along the road, near nightfall, no house in sight,

forty-five kilometres from Steinkopf, forty-five to Vioolsdrif.

This is an example of poetry doing the work of poetry, of a writer crafting words in such a way that they gesture beyond themselves, beyond the normal scope of language. This image moves us beyond the historical moment in which it takes place, while still critiquing it, calling it out in such a way that its desolation is seen and felt. And this was written early in his career. His ability only matures with time, giving birth to a poetry that is irreducible due to its alliance with silence.

The soul of any historical moment cannot be felt in its politics, but in its art and, above all, in its poetry. For it is in the poems that we can glimpse the human lives that took place there. Poets know how to love their time and place, because they resist reducing them to terms that they can understand. Perhaps this is why Coetzee says that “Stephen Watson is a better poet than his time ... and place ... deserve” – because he stayed true to a time and place that couldn’t give him anything in return, but a south-easter, blowing through a “palm, bearded / with dead branches, leaning as if dreaming.” For Watson, poetry was a language outside of history, whose spaces and silences could lead us to a vision of ourselves beyond the barbarity of ideology. He was an example of that metaphor he so clearly admired – “the music in the ice.”

Bibliography

Four South African Poets: Interviews with Robert Berold, Jeremy Cronin, Douglas Reid Skinner, Stephen Watson. Foreword. Gareth Cornwell. National English Literary Museum (NELM) Interviews Series Number One: 1986.

Molebatsi, Natalia. Ed. We Are . . . A Poetry Anthology. Rpt. 2008. Penguin: Johannesburg, 2011.

Watson, Stephen. In This City. Rpt. 1986. David Philip: Cape Town, 1988.

------- The Other City: Selected Poems 1977-1999. David Philip: Cape Town, 2000.

------- The Music in the Ice. On Writers, Writing & Other Things. Penguin: Johannesburg, 2010.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project