Vumani Oedipus being staged at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.

Samuel Ravengai, University of the Witwatersrand

The Western dramatic canon has been a source of irritation to some Afrocentrists, who see it as providing unfair criteria for judging new work in Africa. Some call for its total abandonment and pursue performance modes that are relevant to Africa. I argue for its appropriation and repurposing in order to address Africa’s cultural needs.

There are several models in which this process can be carried out.

The Black Orpheus model

The first model is generally called transposition. Some American scholars call it Black Orpheus. African playwrights create African equivalents of Western dramatic classics with a direct one-to-one correspondence.

Ola Rotimi’s The Gods are Not to Blame, based on Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, follows the same schema. In it Oedipus becomes Odewale, the setting changes from Thebes to Kutuje and all other names are changed to Yoruba equivalents. The Greek culture becomes a metaphor. A new text is formed which addresses African issues but with Greek structural underpinnings.

Welcome Msomi’s uMabatha which was first performed in 1971 at the University of Natal’s open-air theatre, did exactly the same thing. It was based on William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but changed the setting to 19th-century Zululand during the reign of Shaka and Dingane. Banquo became Bhangane, Lady Macbeth became Kamandonsela, Duncan became Dangane and the Thane of Cawdor became Khondo. It was performed entirely in Zulu.

Through this process, Msomi was able to re-programme the play’s reception as an African play dealing with African issues. Apartheid South Africa was preoccupied with the Afrikanerisation of theatre and the sidelining African culture and performances. Due to the activities of the Black Consciousness Movement, most radical theatre activities were banned during the time.

The performance of uMabatha was allowed under the pretext that Africans were complicit in their cultural colonisation. Yet the transposition of Macbeth decolonises Shakespeare through the insertion of Zulu dances, songs, drums, costume and praise poetry. The Zulu culture under threat from apartheid is revived and celebrated under the guise of Shakespeare. It was an incitement outside of the controls of censorship.

The Black Athena model

The second model of repurposing Western dramatic classics, especially of Greek origin, is “reclamation” – sometimes called “Black Athena” by diasporic Africans in the US. The creative impulse emanates from the historical fact that much of the material contained in Greek plays is of African origin. According to the Greek father of history, Herodotus, the Greeks received their myths, gods and culture from ancient Egyptians who were phenotypically a combination of yellow and black.

Dionysus was a version of the African Osiris god. The Egyptians created performative theatre which was stolen/copied/appropriated by the Greeks as dithyrambic singing and dancing. But they later developed this into the dramatic canon associated exclusively with the West. According to this paradigm, to select material stolen from Africa and reinserting it back into Africa is not cultural colonisation, but a corrective returning of the culture to its rightful owners.

While the occult dimension of Western theatre has dissipated since the rise of the western bourgeoisie rule, it is still a part of the African theatre. My play Vumani Oedipus celebrates the power of the metaphysical world over humans.

Re-historicising

The third model can be achieved through conceptual casting and re-historicising the old classics. In this model the origin of Greek culture is of little importance. The Greek play is taken as it is and performed in a new context to speak to a different set of history.

In 2004, I staged Jean Anouilh’ Antigone (an adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone) at the University of Zimbabwe’s Beit Hall Theatre. Zimbabwe was five years into an economic and political crisis. I used an all-black cast and invited the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) to record the play. It happily accepted.

In the play, Antigone calls for civil disobedience over the dictatorship and heartlessness of Creon. Without changing a single word and through re-historicising and conceptual casting, the play had a different meaning to that of the original and was perceived as anti-Mugabe. ZBC refused to air it.

Similar results were achieved through the South African Antigone in 1971, which was performed by students involved in Theatre Council of Natal. The apartheid government gave the students blessings to perform the play, but the students used it to critique the government.

The play opened with a black man being hanged. They used projections of the slums of South Africa to draw similarities between the dictatorship and injustices of Creon and those meted on blacks in apartheid South Africa. In both cases the injustices of Creon were interpreted to mean the injustices of the local context.

Vumani Oedipus being staged at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.

Wits Theatre

Vumani Oedipus was recently staged at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg. The work is inspired by the classical playwright Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

I did not faithfully follow Sophocles’ play. Rather, I directorially reinterpreted and reworked it through, among other things:

- adding new material from other texts;

- collapsing other characters, such as priest and senator into one (Ndunankulu);

- simplifying language and cutting dialogue; and

- re-historicising the play and reprogramming the reception of the story, theme and character.

I also did not resort to the extreme method of adaptation which virtually destroys any link between the source text and the resultant performance text. I wanted to capture the spirit of the old story in a new South African context: Nguniland of the 21st century. The new setting is fictional, but interestingly familiar to South African audiences.

Is there value in reviving Western classics in post-colonial (South) Africa? Is this not perpetuating Western cultural imperialism?

While I respect the view that Western classical canon when used unwisely can perpetuate cultural domination, I put forward views that can be considered when deciding to adapt these classics to enrich African culture. In this globalised world, negative identity is inappropriate. The whole Western modernist tradition is anchored on ideas stolen from Africa and Asia, and Africa can do the same as I have suggested above.

![]()

Samuel Ravengai, Senior Lecturer in Directing and Performance Studies, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

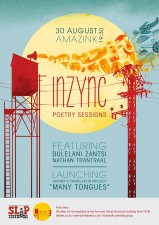

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project