by Lia Snijman

Firsts

“Miesie Muis is ’n klein, liewe, grys muis wat baie van koek en boeke hou.”

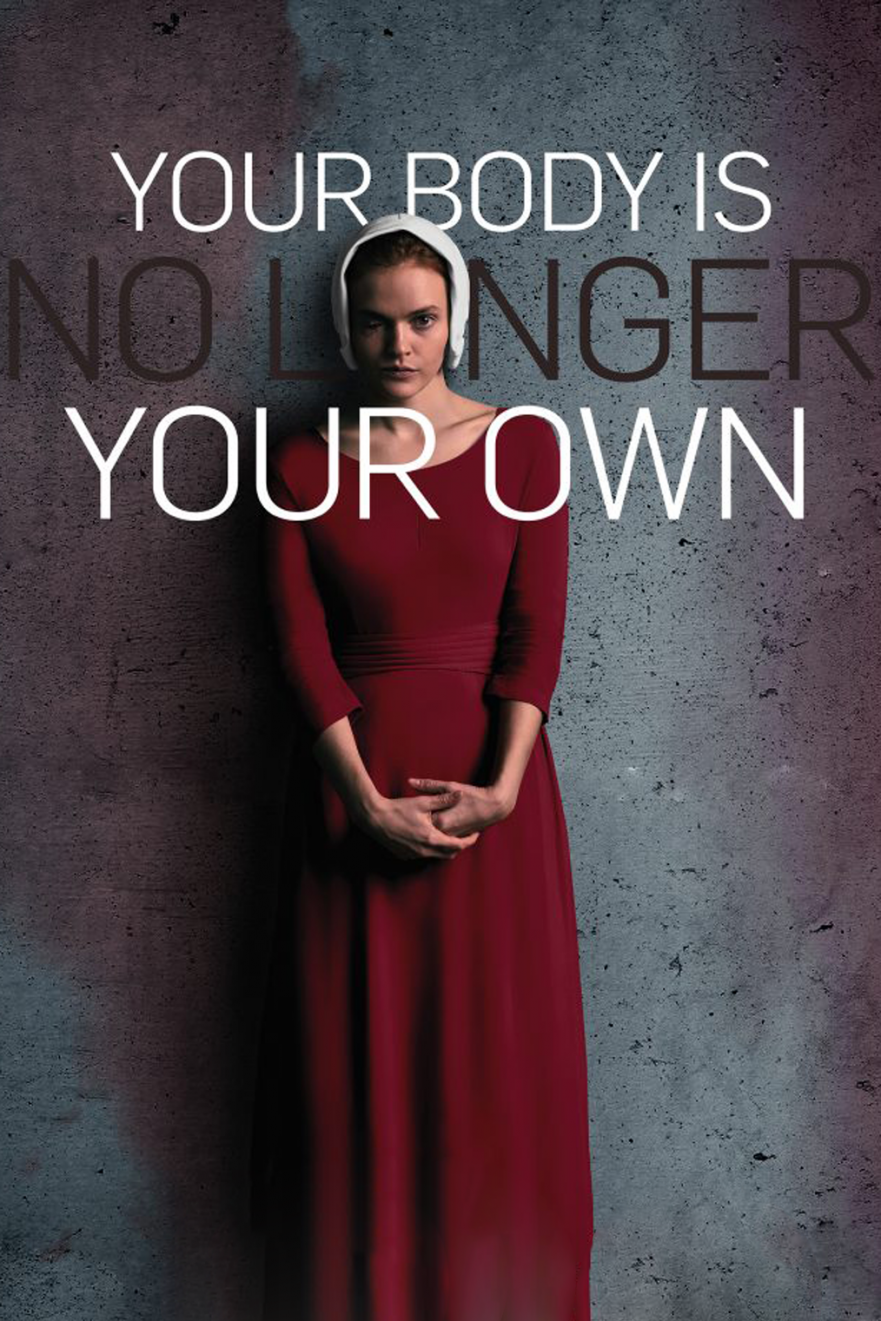

The first significant library in history, we’re told, was the Library of Alexandria, built and opened in the third century BCE. The earliest libraries were archives of transactions and correspondences. These were mostly run of the mill things: who bought what at the market; messages between government officials; legal texts. A quotidian record. Later on things got more interesting with myths and religious texts also being written down. Stories and ideas became much more concrete and easier to share. It was no longer just facts that were deemed worthy of sharing, but inherent beliefs and stories that shaped people’s lived cultures. And so we have records of texts such as the Book of the Dead, an Egyptian funerary text with spells to help the dead through the underworld and on their way to the afterlife, equipping them with anything from knowledge to protection.

My first significant encounter with a library was rather more recent in the larger scheme, and yet feels like ages ago, maybe because I got my membership to the Stellenbosch public library at the age of two, in 1999. My mother considered this quite late, and was annoyed that The System would not let her get the card any earlier. I mean, why wait? She was itching to show me all the lovely children’s books. But at the relatively late age of two, my journey began, and my mother claims that when she woke up in the mornings, she would find me sitting next to my pile of borrowed books, paging through, reading quietly and contently. I wonder if I remember this, or if it’s my mother’s record that forms the archive of my memory.

Now, I look through my childhood books, archives of what little Lia liked: flowers and kittens, in books like the Secret Kitten series and my compendium about flower fairies. My favourite fairies were the ones who coloured their outfits a bright yellow by rolling around in pollen. Later on things got more interesting, with pirate princesses and magical books - Portia the Pirate Princess and the Harry Potter series both still hold dear, if very different, places in my heart. Portia was a princess who became a pirate because her dad had chosen a drippy husband for her. She thus opted to rather sail the seas and bravely save her cousin from a similar fate. And then people wonder why I grew up a feminist. As for Harry Potter, well, everybody knows about him. The mixture of funny lines, clever word usage and incredible fantasy world building and character development stretched over seven books, and this laid the foundation for my love of fantasy.

Catalogues

“We like lists because we don’t want to die.” – Umberto Eco

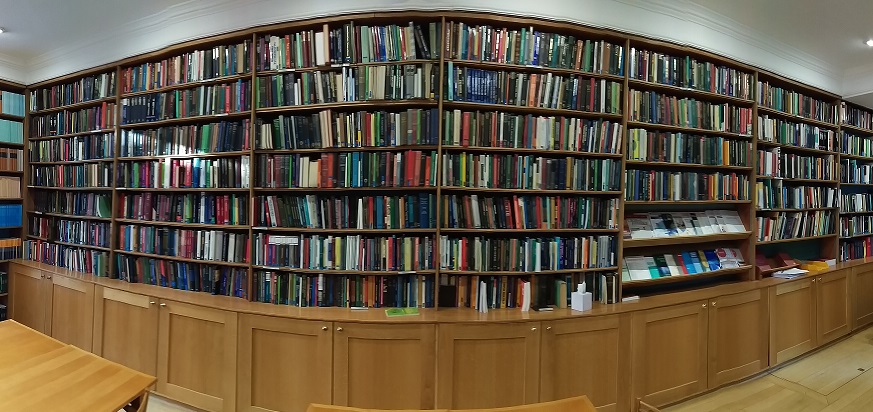

The philosopher Laozi was the guardian of books in China’s earliest library and we know of his, and other librarians’, presence thanks to catalogues. Catalogues are fantastic for organising and remembering things. What is the point of having all these amazing texts and all this information if you can’t find the right things? Or, even worse, if it’s not documented properly. I too have catalogued my reading experience, leaving my Excel sheet behind for future generations to philosophise about how I made the jump from Reënboogrant maats (think 7de Laan, or any TV soapie really, but for kids) to Language Wars: A History of Proper English (a book that is somehow simultaneously more and less pompous than it sounds). There’s something very appealing about the order and accessibility of catalogues. They promise us we’re in charge not only of the present, but of how the future will access us and our information.

Bibliophile

“If you have enough book space, I don’t want to talk to you.”- Terry Pratchett

The one thing that did stay consistent during that transition from kids’ books to serious books, was books. Books and more books. More accurately, my love for books.

I’ve discovered that I am a ‘bibliophile’, a lover of books, a term which entered the English language in 1824. Being a bibliophile is not all sipping hot chocolate and reading in rainy weather mind you – either you have to shell out hundreds for your paperback babies (and if you’re spoiling yourself, hardcover keepers who break your back), or you commit to some form of e-book only to be reprimanded for killing off books, reading and culture in general. Buying new books is a costly exercise (and the increased VAT is not helping) which unfortunately makes it quite elitist and much less accessible than it needs to be. Conditions like this can give book lovers a bad name, and make bibliophilia sound like a communicable disease.

Back in 1812, Lord Spencer and the Marquess of Blandford were well known for being bibliophiles – I suppose their stations in life offered them the necessary affordance - and they famously competed over a first-edition of Boccaccio’s The Decameron, the book that tells of some Italian gentlewomen and gentlemen who share stories in a secluded castle to keep out of mischief while they wait for the Black Death to pass. A frivolous luxury, some may sneer, but as a book lover I can imagine worse ways to spend my limited lifetime.

And think: can’t you just imagine the auction of this rare edition of The Decameron? Everyone excited about seeing what they could snatch up from the Duke of Roxburghe’s library, ready to try and outbid their friends. Spencer and Blandford’s bidding and counter-bidding raised the price of this rare book to a previously unheard-of sum: £2 260. The figure seems astronomical and it would be far beyond my book lover’s pocket. But luckily, in the long run, they must have boosted the growing second-hand book trade, because thanks to them (I like to think) I was able to purchase Boccaccio’s The Decameron for R2 at a book sale on the Neelsie’s deck, at Stellenbosch University. Not a first edition, granted. It’s only an Everyman Paperback that contained an old moth who is now encased among knowledge because of its ignorance. But I have still had the rare pleasure of spending almost an hour rifling through old books and junk to find this gem, mine for the taking because I happened upon it and realised its worth. Which surely is more than two rand?

So I’m hooked on books, and have been since I was a child. In school, finishing with my work quickly in class was great because it meant I could read. I remember feeling personally offended when one silly primary school teacher told us that if we were done with our work we had to draw. Draw? I was stunned. What had happened to reading as an option? I think I settled for drawing a picture of me reading, hoping the teacher would catch my not so subtle hint. I love reading, and I think it might be because I’m somebody who likes observing more than participating. I can disappear into a book, paradoxically finding out more about myself by delving into the lives of others. Perhaps I love books because of the interesting ways that they can offer knowledge and insight. Yes, yes, we have Google, I know. But it’s not just about the information, it’s about how the knowledge is presented to you – in a story where it is much more memorable and pops up without having used cookies to track whether or not you’ll like it. From when I was a child, every Christmas I would ask for a book, and I would be given the newest book in the series I was reading or a dependably engaging Terry Pratchett novel. Even now, each Christmas, books are high on my list of desirables. For this Christmas, though, I don’t want new books that I haven’t read yet; I still have too many waiting for me. However, I am planning on expanding my personal library by asking for

George Orwell’s classics Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, books that I have already read but would very much like to hoard in my room all the same.

The Language of Taste

Bitterbessie dagbreek

bitterbessie son

’n spieël het gebreek

tussen my en hom. – Ingrid Jonker

A shift that I have noticed in my reading habits is the move away from Afrikaans books. Being a mother-tongue speaker of Afrikaans, practically all of my first books were in Afrikaans. I learned to read with Miesie Muis’s pictures and Otto’s lift-the-flap books. “Waar is Otto?” asked the text, alongside clear and colourful pictures of the playful puppy busy with his adventures. “Hier is ek!” Otto would bark from under the flap of a table, a basket or a window. Otto showed me around in the world of early language, allowing me to explore. But my mother exposed me to English books from a young age as well, and I was sent to a bilingual preschool, so from as early as I can remember there was always the pleasure of both languages, and the opportunity for choices. Roald Dahl or Pippie Langkous, Secret Seven or Maasdorp. I could choose if I wanted to go sleuthing and have tea or if I wanted to be in a boarding school and get up to kattekwaad. Sometimes worlds collided when we read the excellent Afrikaans translations of Roald Dahl’s books, making these wonderful stories easier to read for us and helping us believe that we too could pay R5 for a chocolate bar and win a life-changing trip to a chocolate factory net soos Charlie.

However, as I became a teenager the Afrikaans books started to fall by the wayside. I felt that most of them were either babying me (trying to push their patronising agendas down my throat), or otherwise they were way too grownup and grandiloquent, too esoteric. It’s hard as a teen to become excited about an Afrikaans girl called Iris, who learns to be happy about staying at home because that’s where she flourishes. (Kwart-voor-sewe lelie. It was our prescribed book in matric, I swear). And the comparison doesn’t gain when you juxtapose this kind of fiction with Harry Potter, The Hunger Games and novels by John Green such as The Fault in Our Stars or Paper Towns, literary hits which have subsequently been turned into movies. Oh, and before some among you accuse me of being a verraaier or hensopper, let me say that my interest in Afrikaans books has recently picked up again, now that I’m studying the literature and the language at university and am mature enough to make sense of the writers of the Sixties, Sestigers such as André P. Brink, Ingrid Jonker and Adam Small, and their cultural-political legacy in major Afrikaans authors like Eben Venter, Antjie Krog and Wilma Stockenström. I can finally grapple with the devastating historical truths of apartheid, Aids and slavery at the Cape, while also experiencing the described joys of womanhood, child-like wonder and intellectual as well as passionate love. Still, it’s a difficult business, for Afrikaans writers. Their novels must compete for attention – mine and that of a wider public – with a plethora of classics and recent fiction in a worldwide English. Shame. But somehow they seem to pull through, and there’s a market for Afrikaans fiction even beyond South Africa’s borders, in countries like the Netherlands, and Belgium. Increasingly, too, award-winning Afrikaans fiction by major writers such as Marlene van Niekerk and Ingrid Winterbach is being translated into English, and other languages, reaching the world audience these authors deserve.

Books and Looking to the Future

“Fiction is the great liar that tells the truth about how the world really lives.” – Dorothy Allison

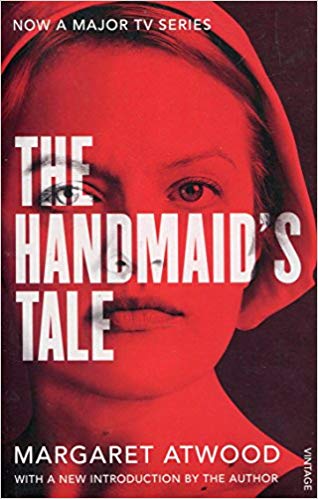

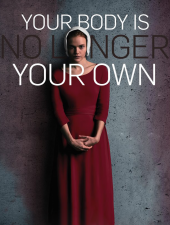

Recently I started thinking about the future of our world in general, but also specifically about the future of reading, thanks to Margaret Atwood’s brilliant The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) and the Hulu TV series based on the novel. Both show us a dystopian USA where women’s rights are a thing of the past because the theocracy believes that the only way to deal with the alarming drop in fertility is to force the women who are fertile to be handmaids to powerful men. The job of the handmaid is to be impregnated by a commander in a ritualistic rape, the situation excused by the perverted twisting of a Bible verse. What specifically made me think of reading is that the handmaids are forbidden to read, or to write. This implies that the government recognises the power, the authority, that can be gained from authoring something to be read, an empowerment which is potentially spread further via the process of reading and the thought and identification so often prompted by reading.

Given, the focus is not just on books, but also articles and other non-fiction. Offred, the protagonist and a handmaid, is frustrated that she cannot go and check the facts, or the lines of scripture given to them, she can merely passively accept. Some newspapers are censored, and the rest are shut down. Even shops’ names are removed to avoid having women read. Offred becomes excited when she finds a pillow with “FAITH” embroidered on it in her room. The fact that she is so delighted by illicit games of Scrabble, calling this a freedom and a luxury, shows that the act of reading is also about the pleasure of words and the expressive agency of making meaning in language. The pleasure of women, in all its forms, should not be underestimated; we see some rare moments of pleasure carry Offred through her otherwise abusive and dreary life. She constantly keeps herself amused by thinking of things that she had once read, transgressive thoughts such as how flowers are the genital organs of plants. Another thing that keeps her going is reading the quotation which has been carved on the floor inside the cupboard by a previous handmaid: “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum”. As she discovers – after asking the Commander to translate the phrase, during one of their tense, secret Scrabble games – this is more-or-less joke Latin and means “don't let the bastards grind you down”. The expression may be crude pig Latin, schoolboy rather than scholarly, but for Offred it is a radically rebellious text and it becomes her feisty mantra.

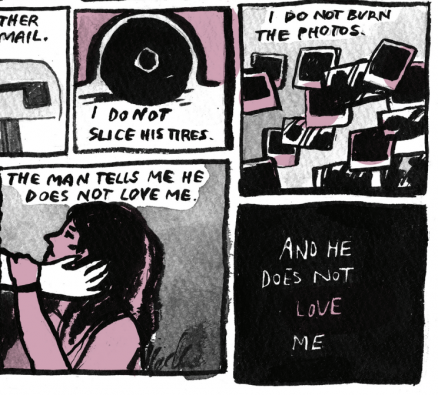

Surprisingly the feminist movement that takes place before the theocratic government takes over was known for burning books, or more specifically, pornographic magazines. Offred knows this because her mother participated in these burnings. So we are coaxed to think about books and their content; to consider who has the right to judge what is and is not permissible, when it comes to subject matters and forms of knowledge. Radical feminists? Religious fanatics? We ponder the challenging question of what should and shouldn’t be allowed to be published, and read, and known. Anything goes? Are constraints an unjust limit? Where freedom of speech is guaranteed, does it take into account attacks on the rights of others?

Atwood, having published The Handmaid’s Tale in 1986, could not have foreseen how relevant this would be in an age where everybody can publish their thoughts and feelings online. One need only look at the current American president, an overt misogynist (not to mention racist and homophobe) who seems to tweet, unfiltered, whatever he ‘thinks’ or hears third-hand on the television, to see the problems associated with giving everyone free reign. Yet third wave feminism has been all about choice and allowing women the freedom to follow paths that society doesn’t necessarily condone, such as using porn, or being a porn star, or becoming famous by writing a memoir about your years in the sex industry, servicing Hollywood’s celebrity men.

Reading and Meaning

“Better never means better for everyone... It always means worse, for some.” – The Commander in The Handmaid’s Tale

I have always valued the use of wit and words to shut down sexism, whether it’s a strong argument or a witty retort, and reading helps us understand words and their power. It also allows us to develop the tools to analyse texts that come our way. In The Handmaid’s Tale we see that many verses from the Bible are used to justify the atrocities committed against women and other marginalised groups in society: black people are called The Children of Ham and moved to separate areas; Genesis 3:16 - “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception: in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children” - is expediently invoked to justify the lack of anaesthetic when women are giving birth. Offred also mentions that the wives of the household are allowed to hit their handmaids because there’s scriptural precedent, and every ritualistic rape through which handmaids are potentially impregnated is preceded by a blessed (in my reading, sanctimonious) intoning of a verse from the Bible.

It’s fiction, I know; just a story from a book, and I should not be so affected. Of course life isn’t really like this. But it’s not like this is completely preposterous in the real world, or near future, either. It doesn’t take much to imagine elements of The Handmaid’s Tale happening, Atwood has after all famously mentioned that she based all events in the novel on real events all over the world. My ex-roommate kept on getting messages from her highly influential church to help ban abortion. They spoke of how abortion means killing an unborn baby which is a sin. These intrusive texts not only sought to police her consciousness, and conscience, implying that she was morally obligated, as a member of the church, to support their zeal. The texts also sought to extend wider social power over women’s bodies, in effect policing women’s bodies, based on the indisputably-claimed authority of religious values extracted from isolated pieces of text.

Reading: our own Stories

“All the reading she had done had given her a view of life they had never seen.” – Roald Dahl

Offred speaks of how she is telling her own story and constructing it. She mentions how it  helps to think of what is happening to her as “just a story”, making it more bearable. I think of how, when I’m arguing with people about the prevalence of rape and rape culture, they always want facts. But I don’t have handy statistics most of the time (and these anyway usually get dismissed as being out of context). I only have stories. The story of my friend who got raped by her abusive boyfriend. The story of how Hannah used to be in my French classes but now she’s dead, raped and killed by random men. The story of how a girl was raped by someone she knew right outside the residence we both live in. The story of the friend of a friend who was sexually abused by her uncle. Yet most of these women can’t share their stories with the public because the person is close to them, because it happened so long ago and they’ve only been able to talk about it recently. And many women and girls cannot speak about their rape because they’re dead. #MeToo unfortunately only gives us a partial glimpse into what happens when the patriarchy naturalises male power, and educates men into violent forms of masculinity. Surely there are other, better stories for the kinds of lives we’d like to live, as human beings?

helps to think of what is happening to her as “just a story”, making it more bearable. I think of how, when I’m arguing with people about the prevalence of rape and rape culture, they always want facts. But I don’t have handy statistics most of the time (and these anyway usually get dismissed as being out of context). I only have stories. The story of my friend who got raped by her abusive boyfriend. The story of how Hannah used to be in my French classes but now she’s dead, raped and killed by random men. The story of how a girl was raped by someone she knew right outside the residence we both live in. The story of the friend of a friend who was sexually abused by her uncle. Yet most of these women can’t share their stories with the public because the person is close to them, because it happened so long ago and they’ve only been able to talk about it recently. And many women and girls cannot speak about their rape because they’re dead. #MeToo unfortunately only gives us a partial glimpse into what happens when the patriarchy naturalises male power, and educates men into violent forms of masculinity. Surely there are other, better stories for the kinds of lives we’d like to live, as human beings?

Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale not only emphasises the importance of stories being told, but also the importance of perspective. Fred, the commander to whom Offred belongs (hence the name “Of Fred”), is surprised when he finds out some of the conditions under which the handmaids live, making her angry at his ignorance, especially because he is on the side of the governing patriarchy that is implementing the bans on reading, writing and almost any control over her own body, and the torture that will come if she resists these proscriptions. Recently, across many popular media contexts, people have been realising how important it is that cultural forms and processes embody the world’s diversity, rather than repeatedly reflecting only the views and experiences of powerful coteries, and historically dominant groups such as white people, in particular straight white men. Audiences have realised that perspective is important if we wish to understand important issues. We have Hollywood calling out…well, Hollywood for not having enough female directors and not giving enough credit to black actors at prestigious events such as the Academy Awards. And within this influential cultural powerhouse, too, we have different factions which challenge the authority of potentially exploitative directors and producers over young actors. In Atwood’s text nobody can risk such open criticism, but we do see Offred hungering for the perspectives of others, wondering about what they’re thinking and what they’re going through. We also see the mistrust created among people because they have no idea what to expect from one another.

So when Offred tells us that the women can’t write and that they can’t read, we need to realise what this means: the women are stuck with only their own, insular perspectives drawn from the brutal constraints of their horrendous experiences, and even these they are not permitted to share. Stay in your lane. Do not look to others for help or comfort. It’s just you who is experiencing this. And it’s your fault. The handmaids are rendered isolated and vulnerable, which is what keeps them subservient, rather than being able to radicalise into a powerful collective with the capacity to effect change. If you think this isn’t relevant for now or the future – take a look at Malala Yousafzai fighting for girls to be allowed to be educated – take a look at how it took 60 women accusing Bill Cosby of sexual assault to take him down – take a look at how Christian women are less likely to report domestic abuse – take a look at all of this and then tell me how women’s voices and opportunities do not need to be amplified in the future. And just remember that, as Offred says, “Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it”.

So if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to do something that is equal parts revolutionary and entertaining, traditional and relevant, fictional and truthful – I’m going to read.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Again, this raises the question: who is your ‘truth’ true for?

Again, this raises the question: who is your ‘truth’ true for? proven useful; their Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives has helped me clear my mind a little about the ethics of responsibility and life writing. But in a sense it has also muddied the waters even more. So right now, I’d prefer to move on to discuss Indian-Dutch writer, Ernest van der Kwast, who writes his autobiographical novel, Mama Tandoori (2010) about his mother who moved from India to the Netherlands, where she married his Dutch father and raised their three sons. While he beautifully portrays the proverbial baggage she brought with her from India, growing up in war and poverty, along with the continual struggle and pain of raising her mentally handicapped eldest son amid the hints of a strained marriage, Van der Kwast uses his imagination and creative freedom to exaggerate and amplify events and family members’ distinctive characteristics to comically recount his childhood and young adult memories. For example, a recurring anecdote threading its way through the novel is his mother’s habit of negotiating discounts on everything she buys: from houses to linen to train tickets to chicken. It seems unlikely his mother was able to bargain her way down to paying only 20% of the original price on a piece of furniture, but this exaggeration of one of her determining characteristics paints a very specific picture of this character, according to the likes and wishes of the author.

proven useful; their Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives has helped me clear my mind a little about the ethics of responsibility and life writing. But in a sense it has also muddied the waters even more. So right now, I’d prefer to move on to discuss Indian-Dutch writer, Ernest van der Kwast, who writes his autobiographical novel, Mama Tandoori (2010) about his mother who moved from India to the Netherlands, where she married his Dutch father and raised their three sons. While he beautifully portrays the proverbial baggage she brought with her from India, growing up in war and poverty, along with the continual struggle and pain of raising her mentally handicapped eldest son amid the hints of a strained marriage, Van der Kwast uses his imagination and creative freedom to exaggerate and amplify events and family members’ distinctive characteristics to comically recount his childhood and young adult memories. For example, a recurring anecdote threading its way through the novel is his mother’s habit of negotiating discounts on everything she buys: from houses to linen to train tickets to chicken. It seems unlikely his mother was able to bargain her way down to paying only 20% of the original price on a piece of furniture, but this exaggeration of one of her determining characteristics paints a very specific picture of this character, according to the likes and wishes of the author.

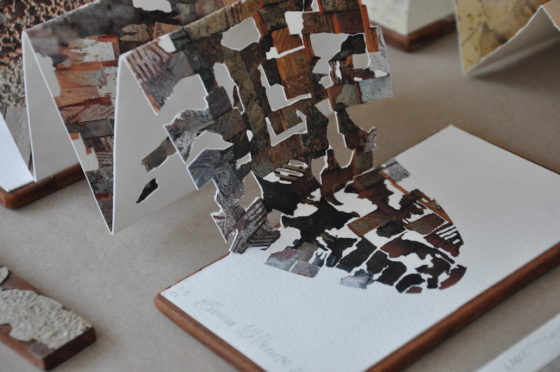

What makes an archive? This one certainly contains many small pieces and uneasily-aligned ensembles that portray loss while simultaneously also serving as a vulnerable storage space for memories and facts, and even the intangible, salvaged ruins of emotion. So Willemse’s archive will always be an incomplete repository, undermined not only from without, but also from within. (I overhear an exhibition guide explaining to a group of visitors that the artist comes into the space every day, and re-arranges the objects on the table. An intriguing gesture, I think: can she take agency over the archive as incomplete? Is this a fragile attempt to control, or to acknowledge the impossibility of emotional completion on the subject of home and displacement?)

What makes an archive? This one certainly contains many small pieces and uneasily-aligned ensembles that portray loss while simultaneously also serving as a vulnerable storage space for memories and facts, and even the intangible, salvaged ruins of emotion. So Willemse’s archive will always be an incomplete repository, undermined not only from without, but also from within. (I overhear an exhibition guide explaining to a group of visitors that the artist comes into the space every day, and re-arranges the objects on the table. An intriguing gesture, I think: can she take agency over the archive as incomplete? Is this a fragile attempt to control, or to acknowledge the impossibility of emotional completion on the subject of home and displacement?)