by Aaliyah Davids

I watch as she steps onto the stage and speaks into the mic, glancing down to read from her pink-clad iPhone: “Alternate Universe in Which I Am Unfazed by the Men Who Do Not Love Me”. The title strikes against my heart, hollow and resonant. And so I start the video again – just in case I misheard. A poet creating another world, speaking the words I cannot.

In her spoken word video of a reading at Button Poetry Live, in just a few beautiful moments, Olivia Gatwood makes simple what so many of us struggle with.

When the businessman shoulder-

checks me at the airport,

I do not apologize.

Instead, I write him an elegy on the

back of a receipt

and tuck it in his hand as I pass

through the first class cabin.

Like a bee, he will die after stinging

me.

Unlike the traditional page poet folded into an anthology, Gatwood embodies her words, stepping out into the gaze of the uncomfortable (Crescenzo, 2018:np). Her spoken word performance allows for an interaction with her audience, during which she shares a glimpse into unrequited love, and the emotions this brings. She is approachable. Emotionally articulate. I feel so easily connected to this poet and relish the retort she has written and now delivers, in person, to her audience: a sardonic elegy, casually drafted on the back of a till slip and delivered in passing to the self-important man, now an indifferent man reduced to ephemera.

***

I stand in the doorway of what is to be my third casting – for some drink I’ve never heard of, called Power Horse. Nervous, the butterflies in my stomach have become bats in a cave, flipping and flicking blindly against my cavernous insides. I take a step through the door, only to be shoulder-checked by a tall man who does not look back to apologize.

Excuse me?

Did he not feel his bone hit mine?

I say sorry under my breath,

yet still await an explanation of some sort.

It does not come.

I walk up three flights of stairs, collect my number and sit down, leaving two seats in between the next person and myself. I avoid eye contact and pretend that modesty is the reason I do this. A white man in a brown leather jacket walks past me, looking for the right door. He makes his way to the next floor, pausing on the staircase long enough for me to look up and for him to gesture with a simple nod: I should join him.

Later still, this white man in a brown leather jacket would be part of the group that I cast with. We will act out the scripted scene: “Youthful and Passionate Entrepreneurs Pitching a New Idea”. Consumed with awkwardness, I drop the ball. He quickly picks it up, maintaining cool composure throughout his performance.

The pudgy director with socks pulled up to his knees, steps in. Tells us to become more intimate; we are colleagues and friends after all. Tells me not to be so shy. The white man in a brown leather jacket, with glasses on the tip of his nose, wearing the glasses as if he didn’t actually need them, puts his arm around my shoulder, for a reason not apparent to me. I continue to follow his lead, improvising my way through the director’s outlined routine.

A few months later, this man and I would be sitting on the beach. He would put his arm around my shoulder in a different performance, wearing a different jacket and a pair of sunglasses that hid his gaze. And I would follow his lead again, this time improvising my way through his own outlined routine.

***

I am 24 and have never cried.

Once a boy told me he ‘doesn’t believe in labels’

so I embroidered the word

‘chauvinist’

on the back of his favourite coat.

I listen. Watch Olivia Gatwood closely. She does not stutter, or falter. She does not seem to be nervous at all, as she confidently brings to life the intense and personal challenges that come with growing up female (Weinstein and West, 2012: 288). Despite her being worlds away, her power becomes my very own. Through the re-ordering of cultural customs and conventions that spoken word poetry involves, she invents a universe where things are otherwise, where the lines between what is and what is possible become blurred (Weinstein and West, 2012: 289). Gatwood paints a world where women no longer cower at the side of the patriarch or the sexist or the chauvinist, but rather embrace the power we’ve always had. She gives us strength not only to say no to the assumptions of gender and cultural chauvinism, but to tear up this script and throw it back.

Her poetic space becomes a “noetic space,” the “zone of the collective imagination that is teeming with alternatives to the actual” (Weinstein and West, 2012: 289). Her spoken word poetry offers inventive ways of knowing, that express her grounded, insightful intelligence. She offers me an alternative reality filled with possibilities that so many young female lives tentatively open up to, but never fully realize. Olivia Gatwood is refreshingly and beautifully outspoken.

***

We sat on the beach and he explained how she had broken his heart, and thus I was made to understand why he did not believe in labels. Or pretend to understand why he did not believe in labels. A label would create expectations that he was not ready for, and despite my wondering what would change if we were to name our relationship, call it what is so clearly was, I did not say anything. I didn’t think myself very demanding. I could not make demands. I reminded myself to be laidback, nonchalant, mysterious even.

He put his hand around mine

and told me how wonderful it was

to be with someone who understands.

“You understand me so well.”

I didn’t answer.

I looked away to the sea

and thought

about how difficult it would be

to embroider something onto the back of a coat.

Did Olivia Gatwood struggle with her stitching? Or was it easy for her to embroider the word ‘chauvinist’ in a painstaking labour of love refused? ‘Chauvinist’ is just one word. Now Gatwood speaks multiple words, online, on stage and in coffee shops, performing her spoken word work. Her words stimulate the concept of the noetical space that “makes possible the imagination of multiple connections, outcomes, and explanations,” and so I see myself pushing the needle through his heavy brown jacket, with ease (Brenneis, 2008: 159). Through Olivia Gatwood’s words, I am capable of anything and everything. Even this strenuous emotional labour of stitching is not beyond me.

***

While the boy isn’t calling, I learn

carpentry.

Build a desk.

Write a book at the desk.

He did not call and he did not message so I did not say anything. I did not do anything. Time passed by quickly yet I remained in the same sad state. Any advice offered fell on deaf ears. Any advice would not, did not, still my aching heart. My heart still ached. I thought of the stories I had heard about people dying of broken hearts. I thought back to each moment spent with him and wondered why he remained so determinedly untouched, when my own poor heart had touched him.

Why?

Why was I so upset?

Why was he not?

Why was I not learning carpentry, building a desk and writing a book, at the desk?

Why not?

In Olivia Gatwood’s alternate universe, I perform differently. I build a desk, a shelf, a chair, another desk. I. Am. Busy. Making. Sense. My time will not be taken up waiting for him to acknowledge me, my feelings and what happened. I need not worry myself over being ready for a call that may never come. Instead, Olivia and I take up the responsibility of handing out hours to the women who have lost their watches, clocks and ability to check for the time on their phones, rather than for his name.

***

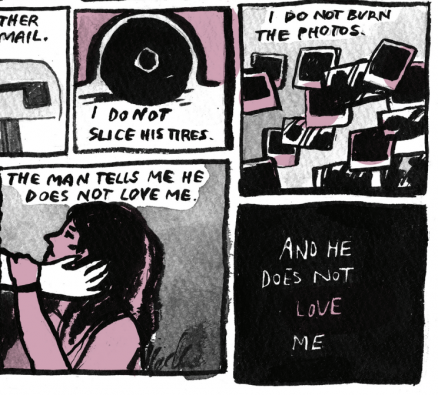

I do not slice his tires

I do not burn the photos

I do not write the letter

I do not beg

I do not ask for forgiveness.

Olivia Gatwood’s female speaker does not do these things. Though I notice how the phrasing leads in through “I do” and so I wonder if, at first, at least in thought, she did. At this point, the poem is a long line of agency withheld by a matching sequence of “nots” and their coupled verbs, so roughly paired: “slice”, “burn”, “write”, “beg”, “ask”. The verbs are finite; firm monosyllables. And yet they tumble over one another, in suppressed, unfinished anger.

In the face of all my own stifled rage and regret, I had to act. After sitting idle, I did what I thought was necessary to forget him. And then I did what I thought was necessary to perhaps win him back. I could not decide between the two. I could not consolidate what I knew was best for me and what my heart so desperately yearned for.

I did delete the photos.

I did write the letter.

I did write another letter

And while I did pretend to be unfazed

during the day,

night time meant the moon moaning with me.

I did ask for forgiveness,

despite having done nothing

worth forgiving.

He was online

but he did not reply.

***

The final act sees us sitting on a battered couch. A blanket has been thrown over it in an attempt to hide the holes where the stuffing peeps out and where the cat has clawed too deeply. Empty blue and red cigarette boxes lie on the stained coffee table, as they always do. Everything in the room speaks (screams) of all-male occupancy. The empty glasses forgotten on the window sill; the dirt on the floor that sticks to your socks; the strangely-placed vase in the corner of the room, and the lingering smell of too much cologne.

I do not make eye contact as he sits next to me, placing my legs over him and handing me a cup of Earl Grey tea, in what he deems an act of intimacy. It is never quite sweet enough. I wait for perhaps a different response, for this time, he knew that what he did was wrong – or rather, this time he chose to acknowledge it and take responsibility.

I do not say anything despite having rehearsed this confusing confrontation in my head at least twenty times. I do not say anything despite the one hundred and twenty voices telling me to yell out something obscene and leave. He pulls me closer. I prepare to improvise through yet another one of his outlined routines. I wonder how many others have performed this scene with him before.

Had a different girl sat on this couch before me? Probably. She was probably tall and thin; long dark hair and fiery eyes that could face his. She was probably the one who broke his heart. Clearly, she had been able to make a decision. I wonder what decision I will make.

He tells me he’s sorry.

“Do you believe me, baby?”

Baby

I’ve always hated being called that.

I look up

from underneath dripping eyelashes,

looking for some sort of sign,

any sign,

that I should

believe him.

Olivia Gatwood’s “Alternate Universe in Which I Am Unfazed by the Men Who Do Not Love Me” loops and echoes in my mind. I remember an interviewer asking her what she would like readers with similar struggles to take away from her writing:

For readers who have read my book and see themselves, I hope they feel, in some way, held by the understanding that they’re not alone, that the process of life and sex and love is not an even or simple trajectory, that shame is not an organic emotion but is instead handed to us by the outside world, and that their memories, regardless of how mundane they seem, are deeply valuable and worthy of being shared. (Crescenzo, 2018:np)

And I do. I do feel held by the understanding that I am not alone in my experience.

This thing called unrequited love.

Such an old-fashioned term,

and yet it pierces me.

And I do. I do believe that he is sorry for what he has done. I can forgive because there is no reason for me to hold onto anger. It does not matter whether he is genuinely sorry or not. He is not worth my anger. He is not worth any more wasted hours. Olivia Gatwood’s enthralling spoken word poetry fills me with a power that does not need this man.

So I take my legs back. I get up. I face him. I look into his brown eyes; allow him five more minutes. He becomes nervous under my gaze but continues to ramble on. For the first time, he holds no power. He is just a man.

The man tells me he doesn’t love me

and he does not love me.

The man tells me who he is

and I listen.

I have so much beautiful time.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project