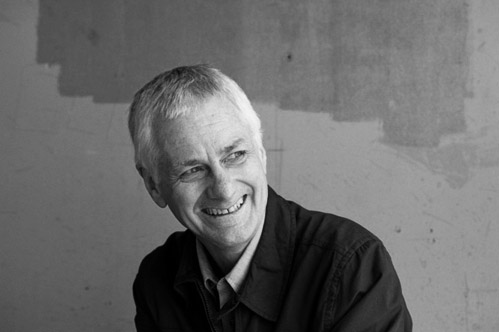

Mike Nicol is, by any measure, a prolific author. Not only is he at the forefront of the South African literary scene, with his latest thriller, Of Cops and Robbers (Umuzi) generating much interest , but he is also a journalist and writer of non-fiction narratives that span an astonishingly wide range of subjects. We badgered Mike with a number of questions, and he responded to them:

WM: You’re probably sick of people asking you about crime fiction, so we’ll start at the beginning, as it were. How did you get into writing?

MN: A story from my school days: The teacher asked the class to learn Wordsworth’s ‘The daffodils’ poem, and as a 11 year old I found it dreadfully boring. So to compensate I wrote a poem about pirates which I read out to the class the next day. They loved it. The teacher called me aside and suggested I not do that again. Well, once I’m told not to do something, I am going to carry on doing it, aren’t I? That was some decades ago now. The poetry carried on through my teens and up to the publication of Among the Souvenirs in 1978. After that I switched to prose as it had long been my intention to write a novel. Some ten years later The Powers That Be was published. Since then, in between the fictions I’ve been lucky enough to write a clutch of non-fiction books. I’d started my journalistic career in 1974, so getting to write longer non-fiction books has been wonderful.

WM: It’s often said that there’s a split in this country’s writing consciousness, with Joburg writers on the one hand, and Cape writers on the other. You live in the Cape, but do you see yourself as a “Cape Writer”?

MN: No, not a Cape writer. At one stage I just tried to think of myself as a writer, in other words, not even as a South African writer or an African writer. But then my subject matter has always been South Africa so these days I see no problem in being labelled a South African writer. Okay, the crime novels are set in Cape Town – there are brief forays to Joburg in a couple of the books – but the Cape Town setting is because of my fascination with this city. It’s also where I live, in fact where I’ve spent most of my life. That said, my awareness of South Africa as subject matter, stems from a fifteen year period I spent in Johannesburg from the mid-1960s to 1980. There I first started writing poems that grew out of Johannesburg. Those poems – some made it into literary magazines but no further – turned my attention to our country. I was also working there as a journalist so the issues that played out in that city and in the politics of those years were the stock in trade of my daily life. If I were to move to Joburg or Durban or wherever in SA I would set books in that place. Simple as that really.

WM: What was your first job?

MN: I worked as a journalist, a job which opened up the country for me. I got to see and experience things which friends working as teachers or accountants or in banks did not come across.

WM: Your novels always display a consciousness of the social and political scenes – they go beyond a merely topical interest in things like the Arms deal, or violence in South Africa in general. How much influence would you say local events have on your writing?

MN: Probably because of the journalist in me local events seep down into the fiction. That said these events may influence the sorts of stories I choose to tell but I try and work from the real event into an event that is true to the fiction, true to the story. Real events can curtail fiction, they impose limitations and it is difficult to be true to what happened in a work of fiction. The type of truth you are hoping for in fiction is of a different order. It is not the truth of detail, but the truth of emotion. When I think of it, in one way or another, some event from either the history of the past or the history of the present finds its way into my novels. At random: This Day and Age was founded on the massacre at Bulhoek and the bombing of the Bondelswarts in the 1920s; while Of Cops & Robbers has the government hit squads of the 1980s let alone current political shenanigans as its cornerstones.

WM: The krimi genre is one that seems to impose certain conventions on those who write in it – a certain style to the characters, a certain way of presenting information. What draws you to this particular type of novel?

MN: The fun of it. Seriously. Look, I was a poet before all else and cut my teeth on stanzas and end-rhyme and sonnets and villanelles and ballads – in other words, on poetic conventions. Form and content were issues. Challenges, if you like. So when I moved to the krimi what did I find but conventions, rules that both needed to be observed and broken. You have to buy into this and after a lot of reading I could see no reason to not go along for the ride. I realised that to break those rules meant you risked alienating a possible readership (people buy krimis because they know the end) but if you are not a blockbuster thriller writer – which I certainly am not – then you have more leeway with those rules. You can, for instance, end a novel with a certain amount of ambivalence. Nevertheless it is writing within the conventions that appeals to me. How do you observe the conventions but still make the characters interesting? Where can you break out and experiment? There is all this to it. But over all there is the parody of the genre and the fun you can have with characters having outrageous conversations after or during the most appalling situations. Appeals to my sense of humour. Crime fiction is satire too. Well, it can be satirical in certain hands.

WM: Your latest novel, Of Cops & Robbers, is fascinatingly topical in its subject matter. How long did it take you to write (roughly), and what were the thought processes that generated it?

MN: That book took much longer than either Killer Country or Black Heart, which were each 12-month books . Of Cops & Robbers took about two years which any crime writer will tell you is a long time. It was a book that started with the hit squad idea and then grew from there. Some of the elements, the urban racing, for instance, came along quite late in the day.

WM: There has been, and continues to be a good deal of controversy over the professionalization of the artistic path. Creative writing is no longer the preserve of the artist lounging in a flat smoking, or roaming the streets in search of ideas, but some people question the idea that writing is a skill that can be taught. As someone who teaches creative writing, what’s your take?

MN: I think there are things that can be taught. The first among them is the discipline of sitting still each day in front of the screen – or blank sheet of paper – and putting down some words. Most people who sign up for creative writing courses lack this ability. After that there are practical issues, for example, how to use description for characterisation, how to use dialogue for characterisation, how to be aware of point of view, how to vary pace, how to create conflict situations – all of these elements can be taught. But while this knowledge can be gained, if there is no writer’s voice – that deeply mysterious thing – then there will be no fiction, at least no fiction that displays energy and vitality. And I believe that in this sense writers are born not nurtured into prose. However, some writers only find their ‘voice’ late in life.

WM: So would you then say that for aspiring writers, writing in an institutionalized way with constant feedback is important?

MN: For some aspiring writers constant feedback is important. I went through a patch like that in my late teens early twenties when I needed feedback on a poem the moment I had finished writing it. But that changes and one becomes less dependent on feedback through the writing of the first draft. These days I don’t want anyone to say anything about what I’m writing until I’ve finished the first draft. But I do see aspiring writers who want some acknowledgement of what they are doing throughout that first draft, and it seems to be useful to them. As there are writers who have come through what you’ve called the “institutionalised way” – Lauren Beukes and Sarah Lotz among them – it does seem to work for some, although I suspect that both of them would have made it anyhow.

WM: Let’s backtrack a little. What is your favourite part of doing what you do?

MN: The writing or the teaching? The writing has two legs: fiction and non-fiction. I enjoy the fiction because it is fun and I’m doing my own thing, creating stuff, imagining stuff. When I write non-fiction I enjoy that because of the discipline of working with the facts and shaping them into a story and the relationship between this story and the truth of what happened. There is always this tension in non-fiction because the soon as you start writing you move away from the truth of what happened. That to me is fascinating. How do we use this marvellous tool we have created – language – to make sense of our world?

The teaching: watching the progress that some students make through a course. They might not ever publish but you can see a marked improvement in their writing – in their understanding of how to present a scene, for instance – and this is always rewarding.

WM: What are your writing habits? Do you have a routine?

MN: My writing routine is simple: I start at 6 a.m. and the first couple of hours of the day are mine. I then go swimming with the sharks off Fish Hoek beach (in summer only) and return to do the stuff that earns the bucks: editing, rewriting (whatever I’m lucky enough to be commissioned for) and the online teaching.

WM: Where to from here?

MN: More of the same.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project