Nadia

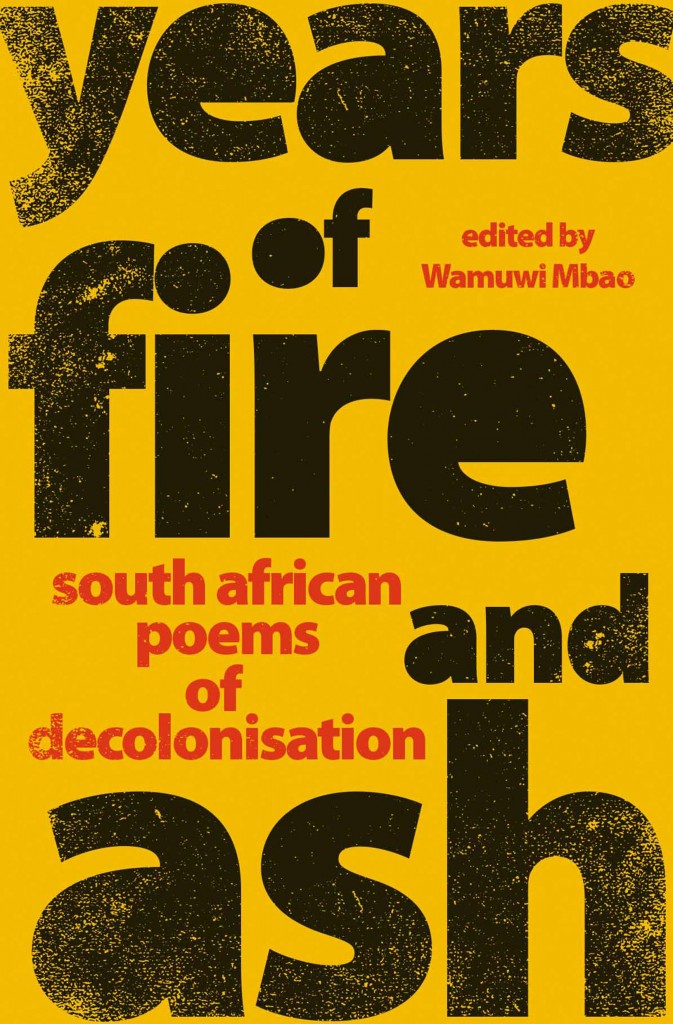

Perhaps a good place to start would be the title. It's a very powerful title, Years of Fire and Ash: South African poems of decolonisation. It brings to the fore ideas of burning with all sorts of historical political connotations, and then after reading your introduction to the collection, there seems to be this disappointing sense of returning to ash. Why this title? Where does it emerge from?

Wamuwi

Well, it is actually from a poem by

Oupa Thando Mthumkulu, called “Nineteen-Seventy Six.” But I think it came out

of this idea that when we were putting the collection together, you know, we

were trying to think about what are the lines of commonality between this stuff

that we tend to consider as struggle poetry. And the current era of political

poetry that comes out of movements like Fees Must Fall and the struggles for

free education and things like that. And I think as we worked on it, it began

to resonate more and more, because, you know, they were all of these points of

commonality that came up especially around ideas of fire and burning. I mean,

remember when artworks were being torched at UCT, and how that was one of those

kind of galvanizing images and moments. And I thought, well, you know, it's an

interesting image to come back to: what happens after the fire? What happens

after these moments? Because, of course I think that this was also one of the

kind of undergirding ideas with this collection, you know. We don't want these

significant poetic moments to disappear when the fire has gone out, as soon as

things have kind of calmed down a bit. So I think that's really as much as it

says, as we thought about it.

Nadia

You speak in the 'we'. You speak as a

collective, represent a collective. And one question I want to ask you -

because I've been thinking about this idea of how there's a long history to

this in academia - around writing as an individual, and being the sole holder

and producer of knowledge, and then writing as a collective or a community, and

how the latter means of producing knowledge is often subjugated and seen as

secondary to being a sole creator of knowledge. Why was producing knowledge in

this collective way important to you?

Wamuwi

I'm always wary of being in a

curative role: when you're the curator, you get the banner head name on the

collection. Now, that's a little bit misleading, because it doesn't really show

all of the meetings and the consultation and the collaborative work that's gone

into this and especially because when I started on this project, I had a

meeting at Jonathan Ball, and the idea

came together collaboratively from there. And while I was placed in a sort of

curative role, when it came to working with a lot of the more contemporary

poets, especially, I immediately began to see that this isn't going to work, if

it's just me harvesting things and putting my own spin on it, you know, so I

began to engage with the poets and say, "Okay, but what kind of collection

do you think we need to be putting out into the world? Who should we be

including, who should we be looking for?" And it really then began to take

shape as a collaborative process in that way. I feel that this is something

which really gave it it's strength; the fact that, even if it is my name on the

front, the kind of work that went into it and the conversations that went on,

means it was it was a group project, and that gave it a chance, because it took

it to places that I hadn't considered. I think I have a fairly good reach where

poetry circles are concerned, but there are a lot of people I haven't come

across and I would have my own biases in those terms. And getting beyond that

was really quite important. You're always self-conscious as an academic of not

projecting your own very narrow reading on things. So being able to speak to,

and work with, people who could then say, "Hey, look at this person",

or "Why didn't you talk to them?" really helped in that regard.

Nadia

And obviously, one cannot choose every

single poem that speaks about, or to, decolonisation over this time period – 20th

century to the second decade of the 21st century. And you do speak

about that in the introduction to the collection. You carefully lay out that

certain editorial decisions had to be made around what goes in and what you

have to leave out. But of course, we know that there's a lot more work that someone

else has to take up at a different time in a different collection. And the

choices are magnificent. I like the way that you've conceptualised

decolonization as this necessarily incomplete, shifting, uncomfortable,

unsettling movement and process. So it's always moving rather than something

concrete. And of course that is central to, I think, how the poems are read.

One needs to move from the position that decolonisation is not this one moment

that will eventually come to an end; this is a moving moment. And what struck

me very deeply is this idea of anxiety that is produced through what you've

called "structural disorder". You talk about how poetry, in general,

is useful in terms of thinking through and conversing with this idea of anxiety,

this South African emotional mood of anxiety. So, I want you to talk a little

bit more about that - this connection between what you call the present sense

of anxiety and the decolonial poetry in the book.

Wamuwi

Yeah, I think that as I was going

through the terms and finding the poems and talking to a lot of the poets about

what kind of mind space they were in when they were writing and putting it

together, something which came to me again and again was always this idea that

there is no way to close off a period and say, you know, "okay,

decolonization is from this time to this time, and it began here and it stops

here." And, of course, you're always running after this sense of thinking

that this could be a 1000 poem collection, if you really wanted to try and harvest

everything, and you still wouldn't have gotten anything more than a small

sample of whatever else. And so very early on I realised that we needed to

think about it in terms of how poetry itself works, which isn't about closed

boxes and things that come to an end; it's something which is ongoing, and it's

not about the easy solutions. And so in terms of this process of - especially

writing through anxiety - what I realised is that after you reach this period

of time, especially with the poetry of the 2000s, if you want to call it that,

where, in addition to these centralised topics, what is actually energising

them, and giving them the sense of activity is this undergirding mood of, “well,

we have achieved democracy, but things are not quite as we want them to be,”

and there are a lot of other feelings that begin to take place. So if you think

about the early poems often being cauterised by the major mood of apartheid,

after 1994, you see this shift of people trying to talk about what might have

been termed minor feelings, things that we didn't really have a vocabulary for;

we didn't really know how to speak about this being important to us, you know.

I think that poetry, in some way, helps people to get at those more minor

feelings, because it allows you to learn, as we often very rarely talk about

how the personal and the political can be deeply affecting; it allows you, as a

reader, to take your own particular kernel of meaning from it, and in very

interesting ways. And I think that the more we went on, and the more poets I

engaged with, what came up again and again for a lot of them, was that anxiety

was kind of their dominant framework for relating to the present; this idea

that so many of the aspects of society that matter to us, occur through this framework

of worry. You worry if you have enough money for your tuition; you worry about

violence of various kinds in the world, whether it be particular to you or

happening in close proximity to you and things like that. And reading this

anxiety, I started thinking that this isn't something that is only about the

present, it actually goes back. Like when you read, say, "Always a

Suspect" by Oswald Mtshali, you've got that sense of anxiety coming

through as well. That's a poem that is traditionally only ever read in that

kind of Soweto poetry framework. But actually, there's a lot more going on

there in terms of what the psychic effect is on you as a person, of living in a

society that treats you this way, that relates to you in a particular way. And

so that's, I think, the thing that really began to take hold as the collection

grew and took on a particular structure. It was about how these different and

very diverse kind of mood generate the same kind of affect in the people who

experienced them, the people who write about them. There's so much more to be

to be said about that. As I was writing the introduction, I was thinking that

there's so much scope for a slightly larger kind of academic volume, but at the

same time, I don't always necessarily know if that's the best output for these

things. So I think that what we put together here gets at the atmosphere of the

present in a way which has maybe wider currency for a lot of people.

Nadia

This engagement with anxiety is an

interesting one. You speak about the psychic effects of living in a particular

society; how those effects have and haven't changed, and the similarities and

divergences in what you call the "same poetics of resistance across a

collection of poems". I am thinking about how the multiple temporal

realities brought about through the combining of decolonial poetry, from the

mid 20th century to now, offers us a trajectory of sorts of poetic

resistance of structures, systems that continue to perpetuate injustice and

injury. The kind of bite-sizedness of poetic narrative makes it quite easy to

read. For me, it's often a mood, and the feeling that it elicits, rather than

trying to analyse it line by line, because that is not, I think, what the

purpose of poetry is. So I want to ask you a question about what you think

these poetry narratives do? What do they do within this process of

decolonization?

Wamuwi

I think that's one of the things that I often

struggle with - and I think a lot of people tend to as well: if you went to school, and you learned about

poetry in a particular kind of way, then I think it either is something that

you click with in a particular way, or it generates a block that stays with you

forever. And I think I fell into the latter category, where, as soon as I see

stanzas of neat writing lines and things, I go, "Oh, it's a poem!" I

don't know what this is meant to mean, and that anxiety immediately sits with

me. And I think I began to think about ways of getting beyond my own block with

this collection. That was part of the reason why I took on the task, you know,

because I was someone who came to poetry with that kind of hangover of like,

"Ohhhh, poetry". And thinking then about what it is that that poetry

does. What is the active kind of work of this kind of lyric output, because

poetry can be so many kinds of thing; in this particular format, it becomes a

printed thing. That's just one output or one form that poetry can take. And so

it meant engaging with the idea of what is it that poetry has historically done

in society. Why is it that certain kinds of poem stay with us in a particular

way? And especially when you think about some of the earlier kinds of poem that

fall into this collection, and some of which are not in this collection, by

people like Serote, or if you think about a poem like "Africa, my

Africa", things which people who would never, ever consider themselves

particularly interested in, throw off a line here or there, because it somehow

embeds itself in the consciousness in a particular way. I think that's something which I began to be

very interested in tracing because there is something in the way that a particular

kind or genre of poem is delivered or in the way that it expresses a particular

source of truth, that sits with you in a particular way and that way might be

entirely personal and subjective. But then trying to trace what is in that

experience of poetry; what is it about? What happens in that moment that we

carry away with us, began to be something of high interest to me. One of the

things that I actually enjoyed about this collection was that, even though the

publisher was quite insistent - and we had quite a strong back and forth about

whether to have things in chronological or non-chronological order, and they

won out eventually – I did intend it to be something that you could kind of get

into at any point because that also then changes the way the poems work in

conversation with one another. So rather than reading it from front to back -

you can do that - if you jump outside of that kind of ideological timeline,

then it creates interesting storylines, like what is it about this or that

older poem that we hear echoing in a poem from forty years later? And it always

comes down to, for me, because people have such different understandings of

what poetry constitutes, "What is poetry to you?", you get ten

different answers to that question. Poetry is not something that has a

particular and exact form. But it definitely has a particular kind of affect.

You know it is poetry because you experience it in a particular way. And that's

the thing, that elusive thing, which you are trying to get a handle on or

looking to, when you put a collection like this together.

Nadia

Yes, what does any writing do? We

know what it does, because we, we feel a response, I think, whether it's

poetry, or more kind of academic forms of writing. I don't know if it is,

should it be? Should we call it completely creative? I don't know. What we know

for sure is that it's political.

Wamuwi

On the one hand, you're dealing with

a lot of poetry, especially with some of the earlier poems that we were putting

together here, which was created with a very strong purpose of mind, poetry

that meant to energise people in a

particular way. For instance, a lot of the poetry is meant to be performed. But

then, I'm taking it and saying ‘but outside of that immediate context, what

else does it do?’ I think nowadays we

tend to be very uncomfortable with the idea of forcing art to have a particular

purpose. That's always the thing that you kick against. Like, beyond its kind

of prescriptive role, what else does it do? And the 'else' is actually the

interesting thing, because beyond that, how do you read, for instance, Serote,

in our context? What is he saying that we might derive any kind of meaning

from? And it's a very vexing question, which doesn't have any kind of easy

solutions.

Nadia

When you wrote your

introduction, who were you writing for?

Did you have an intended audience?

Wamuwi

I think that I had to keep in mind that it was for a collection. And of course, it was helpful that, from the get go, as you said, we don't necessarily think about an intended audience in a very strictly defined way. But, of course, the publisher does because they need to sell books, and so the question of what sort of direction you want to take becomes important. And I think when I was writing the introduction, I had in mind Makhosazana Xaba, who said at a conference once that she thinks about making work legible for her mother or her grandmother, or someone who is not necessarily in the academy, but who is not an idiot. The reader that you have in mind is someone who might not necessarily work within those very kind of specialised frameworks of knowledge that we occupy, but who might be very interested in understanding what these concepts are. So for me, it was about taking a term like decolonisation and moving it out of the academic space, because we all remember when this term began to be bounced around in a local context, and there are all of those news clips, with people ridiculing students for talking about science and maths needing to be decolonised. I think of a moment like that and you see that the ridicule is coming out of people not understanding what this term means, or how it might have application beyond a very localised set of languages. So then when you write an introduction for something like this, you think that you’re not just talking to academics, and in that regard, it was also helpful that because the poems came from so many diverse voices - some of the poets are academics, and some of the poets are performance poets, people who go on stage and recite their poetry and do things in very different kinds of contexts. And all of them have very different, but overlapping audiences, people who are interested in poetry and the workings of it. And I think that's how you then start shaping an idea of your audience; you start thinking that this is a text which should be something that someone can pick up in a bookstore, someone who might be interested in the book, they might like the cover and go, "Oh, what's that?" and then not feel alienated by it. And then similarly, a text which might have application in spaces like the university. One always thinks that you have to keep an eye towards whether this is something that could potentially be prescribed or, taught in a course: those are always your practical considerations. But you try not to let them over inform how you put this together, because of course, then you end up writing a textbook. And there's a broader world out there.

Wamuwi Mbao is a writer and essayist. He reviews fiction for the Johannesburg Review of Books. He lectures at the University of Stellenbosch, where he is based in the English Department. His short fiction has been published in various anthologies.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project