He says he’s a whistle-blower, exposing the corruption and cynicism at the heart of the Kenyan political establishment, all the way into the prime minister’s office. Others describe him as a disgruntled and bitter, a sacked employee with ambition and axes to grind. All SIMON ALLISON knows for sure is that Miguna Miguna has kicked up a whole lot of dirt – and that it probably won’t change anything.

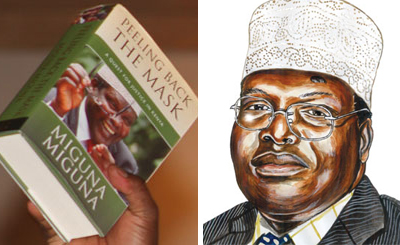

Miguna Miguna, “the man with two names” is at the centre of the political controversy that has taken Kenya by storm, is a larger than life character. He’s loud, prone to exaggerated hand gestures and always dressed in flowing robes and some form of headgear – a sartorial habit that has attracted plenty of criticism of its own, with commentators gleefully pointing out a passing resemblance to Zairean dictator Mobuto Sese Seko. “I dress African. I am a pan-Africanist at heart,” he told one interviewer. “If was able, I would sleep in African pyjamas.”

African pyjamas or not, Miguna probably isn’t sleeping all that soundly at the moment. For the last couple of weeks, the only thing Kenyan politicians and journalists have been able to talk about is his new tell-all book, which claims to lay bare the inner workings of Kenya’s fragile coalition government and attacks the record of prime minister Raila Odinga. “Kenyans have never seen anything like it. The media feeding frenzy was like none other in their history up to this point in time,” wrote Joe Adama in the Nairobi Star.

Much of the talk has been vitriol – and most of it directed at Miguna himself. Things got so bad that one group of villagers burnt an effigy of Miguna in a mock-funeral, complete with mourning dirges and cleansing rituals. Miguna, meanwhile, has taken himself and his family to Canada, on what he says is a pre-planned holiday; critics suggest he’s fleeing into exile to escape the heat, and the anticipated slew of libel lawsuits.

Miguna’s book, Peeling Back the Mask: A Quest for Justice in Kenya, was the fulfilment of a threat. Miguna worked as an aide to Odinga from after the botched 2007 elections until late 2011, when he was sacked by the prime minister for not toeing the party line. Miguna, less than pleased by this decision, threatened to “undress” the prime minister. His book is an attempt to make good on that promise.

In it, Miguna paints a picture of a prime minister’s office stuffed with corrupt and thieving politicians. The politicians are portrayed as venal and self-serving, looking out for their own interests rather than their constituency’s, while the grand coalition government, which has been in charge Kenya since the post-election violence of 2008, is cast as lumbering and ineffective, and always at the mercy of the power struggle between Odinga and President Mwai Kibaki.

Odinga himself comes in for some withering criticism. “I know Raila very well,” writes Miguna. “I know that he is a very weak leader. I also know that he doesn’t believe in, is not committed to, and doesn’t represent the new dispensation … He isn’t dedicated to the fight against corruption. He has no loyalty but to himself and his immediate circle … Through the numerous preferential treatment of his family and relatives, it’s obvious that Raila is a nepotist.”

In addition to the juicy anecdotes, Miguna makes a few stunning allegations. He offers some specifics on local corruption cases, especially to do with a maize importation scam; he insinuates that the results of the 2007 elections were fixed, and that Odinga’s party – apparent victims of the fixing – may have knowingly turned a blind eye; and, most damagingly, he claims that Odinga’s party deliberately stoked up ethnic tensions in the run-up to those elections. It was these tensions that resulted in the post-election violence which killed hundreds, displaced thousands and destroyed Kenya’s hard-won reputation for peace and stability.

Miguna claims he’s got even more dirt that he left out of the book. “Every single leader here, I can take to The Hague [where the International Criminal Court is based]. I have it right here. And I am saying come baby come …” he told his audience, a clear threat to his critics. He says he went easy on Odinga and his party: “When I decide in a 500-page book not to say what the Orange Democratic Movement did in the PEV [post-election violence], they should take me, kneel before me and kiss my feet.”

Kissing his feet is the very last thing the prime minister, or any of the other names implicated in the book, is doing. Although Odinga himself is remaining relatively quiet, the fight back has begun – and it’s taking the form of a smear campaign against the Miguna the “bloviating ignoramus”, as one partisan commentator described him. Odinga’s main defender has been his communications consultant, journalist Sarah Elderkin, who wrote a lengthy three-part rebuttal of some of Miguna’s claims in the Daily Nation newspaper, focusing particularly on the claims of his own self-importance. She wrote that the book was typical of the Miguna she had come to know, describing him as “a person with deeply worrying issues and insufficient personal morality to restrain him from selling his friends down the road, let alone to prevent his embarking on a campaign of all-consuming personal vengeance filled with hatred.” Several lawsuits are also in the pipeline, from figures tarnished in the book, and the director of public prosecutions is looking into whether Miguna should be charged for withholding evidence relating to the post-election violence.

But Miguna himself is not the real issue, for Odinga and his team are working towards a rather grander prize. The real question is whether Miguna’s allegations – regardless of their basis in fact – are strong enough to jeopardise Odinga’s tilt at the presidency in 2013, for which he is favourite by some distance.

Chances are that he will weather the storm. The tone of the coverage of this drama has very much been coloured by political affiliation, with more time spent dwelling on the relative merits of the main players than on the substance of the allegations involved; this suggests that the controversy is merely hardening divisions rather than encouraging anyone to switch their support to someone else. And the reality may well be that Odinga, for all this flaws, is the best of a bad bunch; after all, two of his main competitors, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, are being tried for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.

If there is a lesson for politicians in this somewhere, it’s that people like Miguna are better kept inside the tent pissing out, than outside pissing in. It’s a lesson the likes of Jacob Zuma know well, one suspects, explaining the lengths the presidency has taken to protect such controversial figures as Richard Mdlulu and Bheki Cele.

The lesson for the rest of us is that four years after the post-election violence, and in the run-up to another election, the ethnic and political fault-lines which exploded so disastrously last time round are still very near the surface.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project