In one of its better-written statements the United Nations Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights stated that the importance of a good education is not just the practical skills it gives to young people, but lies in that “a well-educated, enlightened and active mind, able to wander freely and widely, is one of the joys and rewards of human existence.”

(This is an edited extract of a speech given at St Mary’s DSG 2013 annual prizegiving)

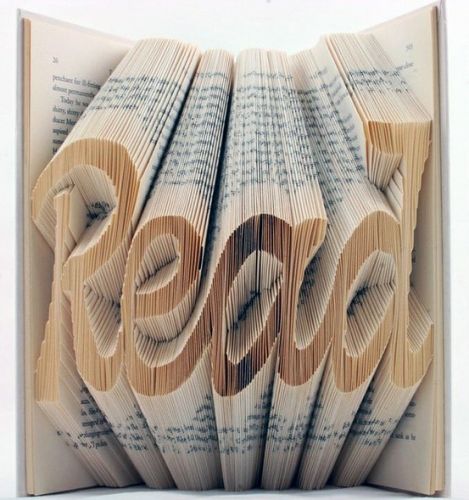

These sage and almost poetic words point to an argument I want to persuade you on tonight: which is the importance for young people of reading and enjoying writing. In particular I want to persuade you of the value of dipping in the treasure of the world’s great literature and thereby finding leads to what will help you to discover and understand the humanity you share with billions of other beings on this planet.

I am an activist. Among other things I am an advocate for the human right to a “basic education” (these are the words used in the Constitution, but they mean a basic quality education). In our campaigns for “basic education” most of the focus is usually on what must be provided by the state in a public school environment. There must be teachers, and libraries, and sports fields, research paper service and toilets, and safety, and textbooks … and, and, and.

All these things are essential. But they are not enough. There must also be a culture of learning. A young person must also want to immerse herself in education. You must feel a desire to invest your effort and stimulate your imagination in what I might call the ethic of learning.

Privileged children in a privileged school have books aplenty, a library, comfortable classrooms and the notion that toilets are a privilege has probably not entered your heads. This relative luxury and comfort is not something I want to berate them for, but it is additional cause to try to inspire them about the importance of reading, writing descriptive essay topics and how it may help them to be better humans.

When you study the histories of great men and women, you discover that often they say books influenced the course of their lives. Nelson Mandela and Chris Hani relate how they were drawn to the books at Fort Hare, one of the few educational centres where young black people had access to extensive libraries. My MA dissertation was a study of reading at Lovedale College in Alice in the Eastern Cape. It took its title from a 19th century black scholar who wrote emphatically in a student magazine that “books made the white man’s success … and they shall make ours.”

But what is so important about books? There are many types of books! But the books I am talking about are books that are containers for literature, which is itself a container of all that is human and all that has ever been perceived by humans. The passion for writing and reading books is a timeless and universal phenomenon. It stretches across the whole of history.

It shouldn’t stop with this generation.

But to me the importance of reading is not just as a way to trace history. It is also about appreciating how reading and writing influence people’s thoughts and commitment – and thereby change the course of history. Reading is a way to witness and understand what makes people human; their loves, their tribulations, the manner they struggle with internal or external adversities. By understanding ourselves we come to understand others and that becomes the basis for lives lived in solidarity with other humans, rather than selfish individuality.

Every language has its literature and South Africa has a fine tradition of its own. But as a schoolboy and university student much of the writing I was introduced to came from the vast tradition of English literature. My middle class life changed after finding the humour, pathos and tragedy in George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. By the time I finished reading it I identified with Orwell’s assertion that “I shall never again think that all tramps are drunken scoundrels, nor expect a beggar to be grateful when I give him a penny, nor be surprised if men out of work lack energy…” When I eventually came across Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot and the immortal speech by the tramp Vladimir “Was I sleeping while the others suffered?” which ends with him lamenting “At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, he is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on. I can’t go on!” I knew that I too couldn’t just “go on”. That I too had to question and confront.

I am making these points partly because, as the father of two 21st century children, I fear the social consequences of the end of young people reading and writing. I witness a lot of inward looking in my children, but it is looking inward into gadgets and computer games – not an introspection of the soul of the type that reading causes! That concerns me.

So, in defence of the habit of reading, let me try and persuade you why reading is more exciting than computer games.

Reading literature is your entry point to the entire world. Writing is a first-hand account that gives you eyes and direct access to any part of the world, any country, any time, any person. By reading you can literally place yourself on the frontline of the world’s battles; read Vassily Grossman’s great recreation of the siege of Stalingrad, Life and Fate! You can grapple with the most profound and tortured expressions of love; read Keats’ painful poems to Fanny Brawne! You can discover people you would never otherwise meet, often long dead, through their biographies and autobiographies. You can be witness to the permanent evolution of thought in science and philosophy.

In the opening lines of Shakespeare’s play, Henry V, a character called Chorus asks “for a muse of fire” that would allow his audience “to ascend the brightest heavens of invention”. The muse is given to him and he succeeds in dramatising some of the personalities, the humors and the tragedies of a battle that took place between the French and English armies in 1415 – a battle that would otherwise have been reduced to nothing more than a date. As Chorus’ success in summoning up the lives of Henry and Falstaff and others confirms, writing is a way to summon the imagination. Reading the play gives you the same results in 2013 as when it was written in 1599. That fact alone is cause for wonder and amazement.

My argument is that reading creates all-rounded beings. However, many might question whether reading is really needed in the 21st century. After all, today you can watch almost anything on TV or you can just Google it.

My answer is that writing gives you a three-dimensional understanding of life that you will not find in television or on the Internet. You have to do work to read – rather than just be led by fast and flickering images – and the effort forces your brain to imagine and to create. The concentration required in reading, the focus and isolation, the play of words, enables your mind to wander and to start its own processes of thought and creation. Joining the dots of history through your imagination helps you to draw conclusions about the lives you live.

My message is that that world is simultaneously beautiful and bad. You have choices. You can selfishly embrace the good, take it for yourself and your family, but you can’t escape the bad. That being the case, you might as well seek to shape the good, and limit the bad. If you accept my argument, reading and writing will instill in you a sense of others’ humanity and hopefully from that will come a belief in justice and other people’s rights to dignity. That will make for a better world.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project