This blog was first published by www.tangerineandcinnamon.com on 6 January 2014

This blog was first published by www.tangerineandcinnamon.com on 6 January 2014

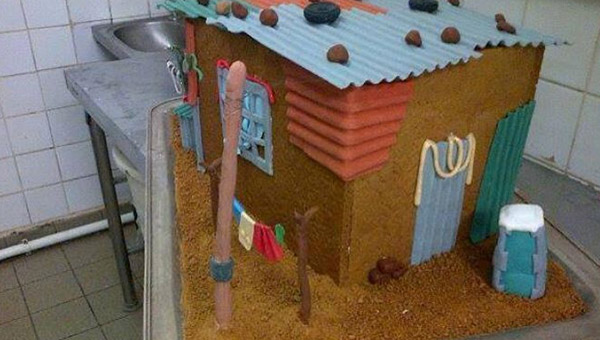

Just before Christmas last year, the Mount Nelson – Cape Town’s grandest hotel – caused a minor kerfuffle on social media after posting a photograph of its latest confection: a corrugated iron shack made out of gingerbread. When several people pointed out that this was, at best, a stunningly insensitive gesture, the hotel’s representative replied that its purpose was partly “educational”: that it was to “raise awareness” among hotel guests, most of whom are foreign, of the Mount Nelson’s “township projects”. As the uproar grew, the hotel deleted the photograph, then denied deleting the photograph (arguing that it was trying to “control” the outcry), and finally apologised – blaming the gingerbread house on a “staff initiative”.

This is not the first – and will certainly not be the last – example of crass, thoughtless behaviour in the food world. A couple of years ago I attended part of a conference-cum-festival in the Cape Town City Hall where an installation attempted, through the medium of cake decorations, to impress on punters how many South Africans are illiterate, use latrines, are HIV positive, and are unemployed. (The same event included a talk on Nelson Mandela’s life understood through food, during which members of the audience were served versions of the meals that he ate at key moments…supplied by posh supermarket Woolworths.)

Earlier this year, a group of Hackney hipsters were forced to defend their decision to open an advice centre-themed café on the former site of the Asian Women’s Advisory Service. The Advisory – as it is called – seemed to many to crystallise all the worst aspects of the gentrification of one of London’s poorest boroughs.

The Advisory and that Cape Town food conference are the products of an industry dominated by the privileged. The Mount Nelson’s defence of its gingerbread house could only, I imagine, be made by someone who had never had to think too deeply about the circumstances which force people to live in informal settlements.

So far, so obvious. But I think it’s worth paying attention to the Mount Nelson debacle, in particular, because it draws our attention to the problematic ways in which the food industry – or the collective writers, broadcasters, restaurateurs and others involved in the food world – deals with race.

Recently, and most noticeably since Time’s disgraceful male-only list of the world’s top chefs, there has been a lot of excellent discussion about why women’s contribution to the food industry goes unnoticed. But we have to ask another question just as urgently: why is it that the majority of people usually listed as “top chefs” (whatever we may mean by that) are white? Why is it that someone like David Chang is a notable exception in a long parade of white men?

It certainly isn’t the case that kitchens don’t employ black people. The report Fast Food, Poverty Wages: The Public Cost of Low Wage Jobs in the Fast Food Industry (2013), demonstrates not only that Americans employed in fast food jobs are more likely to live in poverty, but also that “[m]ore than two out of five front-line fast-food workers are African American (23 per cent) or Latino (20 per cent)”. More generally, the majority of people employed in low-paid, but essential, jobs over the extent of the food chain – from agricultural and abattoir work, to shelf packing and restaurant serving – and in the US and elsewhere, are people of colour.

The invisibility of this workforce in most food writing is indicative, I think, of the, often problematic, ways in which food writers deal with race. Food writing is one of the few genres where it’s still possible to describe Middle Eastern or south Asian food in terms that would keep the average eighteenth- or nineteenth-century orientalist happy. This post on how to write about African food – inspired by Binyavanga Wainaina’s essay “How to Write about Africa” – nails this:

It is best practice to include the word ‘Africa; plus a positive descriptor in your headline. If you must be more specific, whole regions like West Africa, Southern Africa, East Africa, West Africa or Central Africa will do. Always keep the headline of your article broad, even when writing about the food of a specific country.

…

Remind the reader that Africa is not a country, but still do not offer specifics.

…

Introduce the owner of the restaurant. If male, he moved to the country 10 years ago and learned to cook by working in the restaurant of a hotel. Another option is that he had no idea how to cook upon arrival and taught himself everything he knew after a bout of severe homesickness. His name is Chuck.

If female, she is a motherly figure who walks round greeting customers as if they were family. Think Mother Africa. She has a twinkle in her eye. She is plump. Everyone calls her Mama O.

Ask Chuck or Mama O why they chose to open a restaurant. Ask about the name of the restaurant and what it means.

Discuss the menu and gloss over the regular dishes… Focus on the most exotic-sounding foods.

Point out that Mama O brought out a knife and fork for you, but you endeavored to go ahead and eat with your hands. Mention that you cleared your plate. Don’t offer criticism.

My point is that the kind of bad food writing this post parodies, is indicative of a set of deeply concerning attitudes towards race: that Africans (or Asians, or South Americans…) conform to a set of exotic stereotypes that render them less fully human than the white, western writers who encounter them. One of the effects of this writing – which has a tendency to describe all non-western food as “ethnic”, as if whiteness absolves one of ethnicity – is to draw attention away from the material circumstances in which Ethiopians, Iranians, and Mexicans, for example, actually go about producing food, either for themselves, or as immigrants in other societies.

Put another way, this food orientalism serves to depoliticise writing on food, and to distract from the inequalities and exploitation that occurs along the length of the food chain.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project