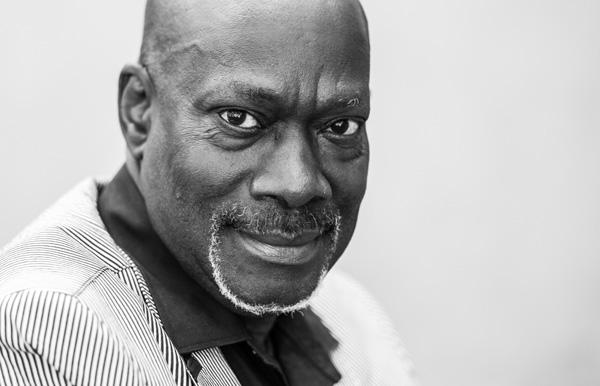

Photo by Retha Ferguson

Dancing in Other Words, 10-11 May 2013, Spier, Stellenbosch.

Writers of the so-called “postcolonial” nations have not typically enjoyed the same insulation from politics and geopolitic anxiety as their counterparts in the metropolitan bourgeoisie of Europe and America. The presence of the political – explicit in hunger and infrastructural failure – exerts a pressure, whether real or spectral, on the imagination of its artists. Nigerian author and public intellectual Kole Omotoso speaks of the Dancing in Other Words festival as comprising a “dual experience”: the creativity of performance, the organising discourses of panel discussions. In that sequence alone, already the contour of the usual complement of questions present themselves: where does poetry interpose itself between the fictional and the social; what, in other words, is the position of poetry to the world? It is a topic which he chairs later at “The World as Decayed Metaphor” seminar, but this morning I have a pre-emptive opportunity to ask him these questions in the colonial Manor House of the sprawling Spier Wine Estate; in the distance, the tribal percussion and rhythm comes off in jagged waves from Moyo restaurant, that tribal confection of tourist exoticism.

“Even as a participant,” Omotoso begins, “it is difficult to apprehend the totality of the experience [the festival].” He speaks of the “unpoetic” nature of the discussions, which deal with “life out there” (ethics, translation, reality), and their juxtaposition with the “magic of performance”, “the magic of that communication that says that all that matters is creativity… it affirms us; it restores us from the amnesia of the quotidian. It makes it possible for us to stand up and simply contemplate […] Poetry makes it possible to dig deep into yourself, and hopefully to bring out that humane possibility that makes life worth living.” This belief in a restorative or spiritually-replenishing power of the poetic is one shared by many participants at the festival.

Omotoso goes on to speak of the impacts of reality on poetic production. He has felt its intensity first-hand, having lived in Nigeria where access to electricity is capricious and “the roads are illiterate”. He says that “when you live in a place like London, New York or Paris, the infrastructure makes you forget the necessities of simply being functional: the fact that you switch on the light and it comes on. If you live in Nigeria, unless you have a generator, or two or three, you cannot depend on having power.” He says that when simple things – like charging phones or accessing the Internet – become a luxury, there is a discernable impact on “achievable levels of creativity” and an issue of “underperformance”. He continues, saying that, “it doesn’t matter how much you may say that poetry or novels have nothing to do with politics; politics has a lot to do with you and therefore you cannot be indifferent to it.” To Omotoso, “more than anywhere else in the world today, the so-called third world has been forced to respond to its imposed limitations, but in the aspiration to the next level, we have to take on our situation as well as the rest of the world. No one is willing to accept that now, but they will have to accept it, because there’s no other way.”

If the remarks above engage the impact of the environment upon creativity, they only allude to the manner in which literature and poetry provide creative adaptations of that environment. With regard to poetry and practice, Omotoso speaks of the “escapism” by which poetry helps the writer to “create a space in which to reinvigorate. At the same time, you create spaces to go out there and be part of what exists. For me, what is tenuous and impossible to reach an affirmative conclusion [on], is whether my writing does anything, and therefore my writing – and what happens outside there – can exist within me.” By this he means to mark the polymorphous figure of the human subject, who can act variously in capacities such as the citizen, with a desire for justice, as a poet, “to bring hope to the hopeless. Poverty cannot be defined outside of hunger. If you can take hunger out of poverty, you have defeated poverty. It is nothing like alleviating poverty – it is about eliminating poverty. As they say, the stomach is a rapacious goddess who demands sacrifice all the time.”

From here, the conversation zigzags through the issue of multilingualism and translation, among two of the most repressed phenomena in post-Apartheid South Africa. Omotoso speaks of the importance of translation and cross-cultural communication and affirms the need for a “language industry”. Finally, he marks the need for poets to counter the “degradations of language”, to refine language which has become careless and inane.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project