I look out over Bloemfontein from the top of the hill at Oliewenhuis. I came to see the city from a vantage point which would put my own thoughts into perspective, relativising my small crises against the sprawling mass of humans and machines in this placed called Mangaung - place of the lion. Wild olive trees partially obstruct my view as I try to imagine a time when lions, giraffes, springbuck and various other big mammals roamed these plains before the big Bainsvlei hunt of 1860 decimated the wildlife in the region.

I start wandering down the path to the regal Manor House. Oliewenhuis used to be the home of the governor general and housed several NP presidents from the 60s onwards. Today it’s one of the foremost art museums in the country. I decide to check whether there are any interesting exhibitions currently running and sneak in through the back door.

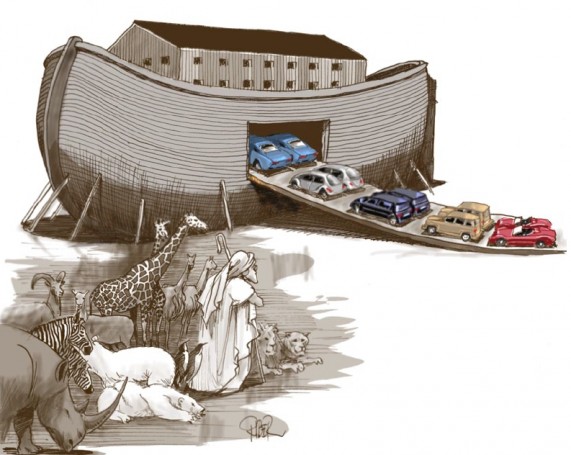

The title board contextualises things for me: Facing the Climate – 5 Swedish and 5 South African cartoonists take a sharp and disturbing look at the climate. The first cartoon I see is simply entitled Ark by Riber Hansson. It playfully, yet scathingly, reworks the Noah story: this time around Noah and the animals are left to fend for themselves and the ark is used to keep motorcars, those icons of gas emissions, safe from the approaching catastrophe. This simple and elegant use of visual language draws me in and I start strolling through the space.

Ark. Riber Hansson. Digital Print. 40cm x 30cm.

Cartoons have long played a vital role in exposing the inconsistencies, contradictions, abuses and exploitations in society, usually employing satire, caricature or humour to bring a point home. The focus is on the visual, imbuing cartoons with immediacy and a directness accessible to everyone. It is the ultimate democratic medium, addressing issues that affect everyone in a way that is easily understandable. Cartoons speak the in-your-face truth with a directness that can be searing, often evoking laughter as a way of masking the dread of recognising the truth of what is being said. It is precisely this visual potency of cartoons that I experienced anew while walking through the exhibition at Oliewenhuis.

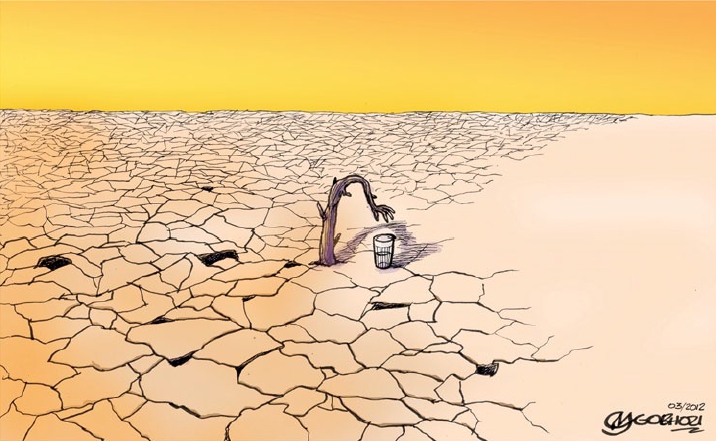

The works vary in style and approach, and the tones range from the elegiac (like Magnus Bard’s drawing of a museum installation commemorating the disappearance of snow) to the accusatorial (Riber Hansson’s amalgamated landscape where the St. Peter’s Basilika and Russian oil plants stand side by side). Furthermore, it is also interesting to note the regional differences when comparing the Swedish and South African cartoons. The artists from the North repeatedly use the disappearance of ice or snow to mark the effects of global warming, whereas Southern artists often invoke arid landscapes stripped of plants. These differences help to accentuate the varied effects of climate change around the world.

Water Please. Wilson Mgobhozi. Digital print. 40cm x 30cm.

The hypocrisy and self-centeredness of governments and supranational corporations is a recurring motif throughout the exhibition, including the senseless to-and-fro bickering that has become the hallmark of international conferences that try to address climate issues. The title of Karin Sunvisson’s print All those lies unlocks the meaning of the horde of flies covering a businessman’s mouth by referencing the well-known metaphor of “talking shit”. The image also plays on the title of the exhibition, literally showcasing a “face” of the climate, representing the kind of people that are employed to deal with climate-related issues in business and government.

All those lies. Karin Sunvisson. Digital print. 40cm x 30cm.

But Zapiro’s ability to summarise complex power-relations and their stalling effects on reaching sustainable solutions to climate change is unsurpassed in this exhibition. In Untitled (The scream), Zapiro references Edvard Munch’s iconic expressionist painting. Munch’s expression of existential angst is aptly adapted to portray the urgency of reaching a global consensus on combating climate change. The cartoon also literally puts the fighting between developed and developing nations into perspective. Their arguments are shown to be misguided and irrelevant to the actual crisis at hand.

Untitled (The Scream). Zapiro. Digital print. 40cm x 30cm.

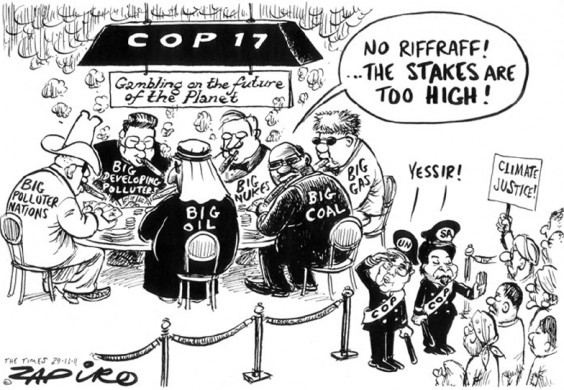

Untitled (COP 17). Zapiro. Digital print. 40cm x 30cm.

The second Zapiro cartoon that caught my attention, is Untitled (COP 17). A group of representatives from all the big fossil fuel nations are huddled around a poker table, “gambling on the future of the planet”. They are only interested in the economic effects of changing our interaction with fossil fuels, responding to a global crisis by playing a game of chance. South Africa and the UN are also exposed for their impotence – they are mere lapdogs in the greater scheme of power and obediently refuse access to the crowd. On the fringe of both the COP 17 talks and the cartoon stand the disempowered crowd, the people who will experience the incumbent effects of climate change most severely. The call for “Climate Justice!” almost seems pitiful in this context where all the power is concentrated among the few while the many are left excluded from talks that will directly affect their and their progeny’s livelihoods.

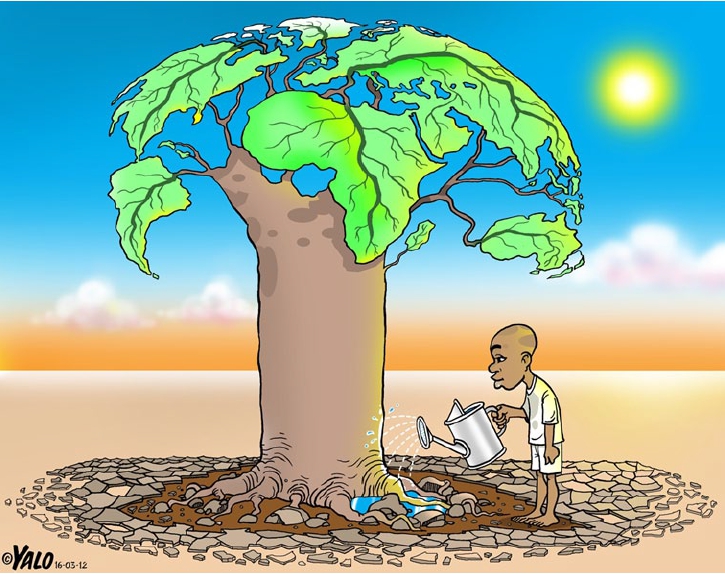

Furthermore, there are also works in this exhibition that have a distinct aesthetic quality – they are, simply put, beautiful. Sifiso Yalo’s Tree of Life and Ree Treeweek’s Migration are two cases in point. Both these cartoons are more subdued than the others, inviting a plurality of ideas in the mind of the viewer without the hit-you-in-the-stomach-directness of most of the other cartoons. Yalo’s cartoon is a visual metaphor of the world as a network of baobab leaves. This not only underscores our interconnectedness with all living things but also points to the fragility of our global ecosystem and how easily it can be shriveled up by the sun. The surrounding landscape is deserted and a lone figure is watering the tree. This simple gesture captures the potential connectedness we feel towards nature and the role individuals can play, despite uncontrollable global changes, by caring for living beings.

Tree of life. Sifiso Yalo. Digital Print. 40cm x 30cm.

Viewing cartoons in an exclusive venue like the Oliewenhuis Art Museum does seem a bit odd, given the usual public visibility and accessibility of this artform. One might ask whether an art gallery is too restrictive a space for this kind exhibition, especially since one of the explicit aims of the Facing the climate project is to “encourag[e] discussion about [a] sustainable society and [to] heighten awareness of current environmental problems,” according to the exhibition catalogue. Admittedly, the exhibition has traveled to various global cities and has purportedly been seen by over 150 000 people, according to the Swedish Institute’s website. But one still wonders whether the cartoons aren’t confined by the walls of the gallery, whether they wouldn’t have a greater impact if they were published, say, online. If the strength of cartoons lies in their visibility, why not increase their strength through a concerted social media campaign, which could turn at least some of these cartoons into viral internet memes?

Despite this reservation about the space in which the exhibition took place, I am still grateful that I managed to stumble upon these cartoons. They reaffirmed the relevance of visual art in an era where we are saturated with images. They reminded me of the contributions artists can make to the global discourse on one of the most pressing issue of our times.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project