Billy Monk’s emergence on the South African photographic scene is curiously occluded: stopped up, absorbed, retained. Across a span of over 30 years, it is the relative absence from general view of his photographs which I find particularly disturbing and suggestive. While deemed a Cape Town “legend”, Monk’s visibility is oddly momentary. Rather like Walter Benjamin’s actors, Monk’s images “enter, fleeing”. Sean O’Toole describes Monk’s photographs as “paper-thin slivers”, evoking the ephemerality of the image, but also their initial traffic as scalped mementoes of illicit intimacy.

The body of work for which he is primarily known was shot between 1967 and 1969 and, we are told, the pictures were sold to the sugar girls, seamen, and other paying customers who frequented Les Catacombs and The Spurs, bars-cum-escort agencies in Cape Town’s Red Light District located in the dock area. Their initial presence, therefore, cannot be removed from the age-old reality of Cape Town as a port city, way-station, or liminal zone, between East and West. Frequented by mariners from across the world as well as by local landlubbers in search of a world outside the oppressive optic of Apartheid, Les Catacombs and The Spurs emerge as ciphers for an untold story, or, a story which could not be publicly told. It is this pervasive silence, this presencing of a world that could not be figured, which explains the deferred, peripatetic, and momentary presence of Monk’s photographs.

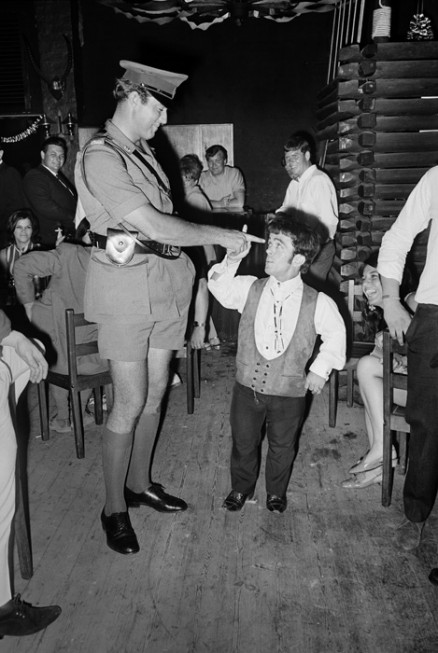

Outide the Catacombs, 21 December 1968 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

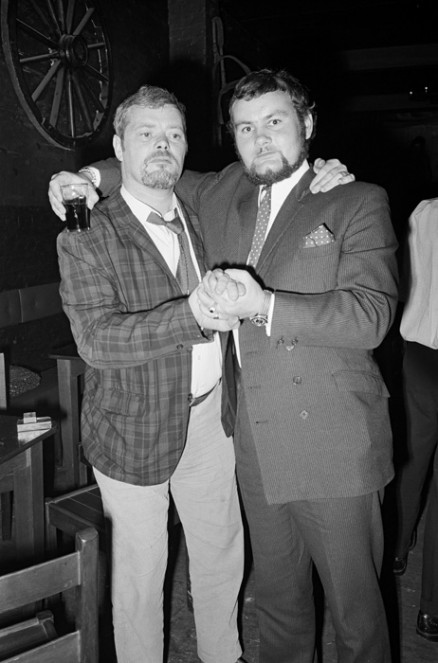

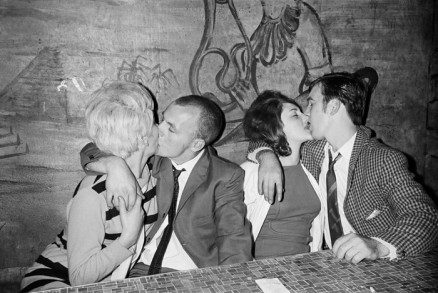

The Catacombs, 27 October 1967 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

The initial reason for their existence is clandestine: the photographs surface, I imagine, in the breast-pockets of mariners; amid the private emporia of sugar girls; or in the case of other local inhabitants, as secreted trophies of some private resistance. Thereafter the images are filed, as negatives, where they languish in Monk’s vacated studio for 10 years before being discovered and reprinted by Jac de Villiers and Andrew Meintjies. An exhibition of 42 of the images of that period follows in 1982 in Johannesburg. We are told the images were unanimously fêted, the entire collection bought by the South African National Gallery.

It is then, in 1982, twelve years after the images were filed away, that they become the subject of Lin Sampson’s moving essay, “Now You’ve Gone and Killed Me”. These are the dying words attributed to Monk, although it is difficult to determine whether this attribution is fictive or true – in Monk’s case the inability to distinguish the two forms is a leitmotif.

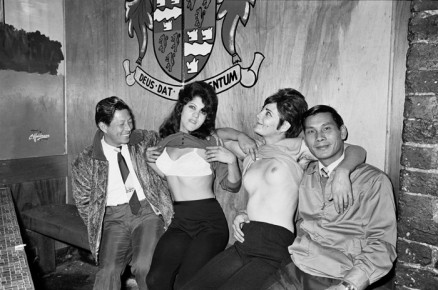

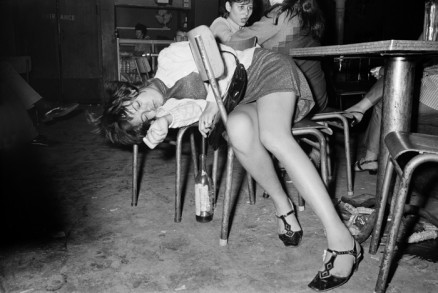

The Spurs, 29 December 1967 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

One thing is certain: they cannot be a reference to the first exhibition of his works, since he failed to attend it, given that he was dead. (Rumour has it that he was shot to death while defending a friend in a brawl regarding the rights to articles of furniture.) Nevertheless, the phrase does invoke yet another occlusion, because a further 11 years would pass before Pam Warne, curator of the SANG, would return Monk’s photographs to the public in her exhibition titled “Jol”. According to O’Toole, Monk was to prove Warne’s “star act”, and as a visitor to the exhibition, I must concur, for it was then that I discovered Monk’s work for the first time.

Barring Lin Sampson’s critical intervention in 1982, little is written about the work. Once again a lull follows, the images receding from view, and, while celebrated, barely critically recorded. Then, in 2010 and 2011, Monk emerges at major Expos in Brighton and at the Michael Stevenson Galleries in Johannesburg and Cape Town. What are we to make of this repeated appearance and disappearance of Billy Monk’s photographs? They seem to flicker in the mind’s-eye, incite pleasure and interest before vanishing again. How do we explain this curious occlusion?

Perhaps history plays its part; perhaps, because their first professional recovery in the ’80s, while inciting interest, proved too risqué? After all, this was the time of Apartheid and the Immorality Act, a time in which images of cross-racial fraternisation were taboo. But then, what of the post-apartheid moment when the images resurface, only to be stopped up once again? For Monk’s images feature neither as figures of resistance art, nor as images of a prescient post-resistance moment in the very jaws of psychic oppression. It seems that it is only now, in a moment neither reactive nor post-reactive, a moment after Arthur C. Danto – when history buckles and disintegrates and the lie of provenance and value eviscerates – that Monk’s images have assumed a certain cultural credibility. Why this belatedness? Why, for more than three decades, have Monk’s images existed under erasure: as cultural phenomena manifest yet cancelled?

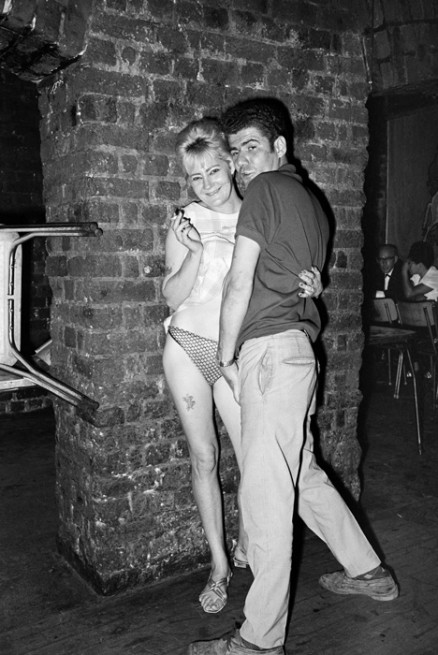

The Spurs, 27 February 1968 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

The Catacombs, 12 March 1969 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

What compels me is neither intrigue nor scandal but the inevitability of Monk’s occluded fate. If Monk’s images failed to be canonised as ciphers of resistance or post-resistance, it is because they by-passed or were suppressed by the cultural cognoscenti operational in these particular times of struggle and putative liberation. But then surely this makes no sense, given South Africa’s new constitution and, amont other radical instances, the emergence in the early ’90s of cultural phenomena such as the Mother City Queer project.

Were the images either prescient or belated? Did they tumble into some black hole; or were they merely some dark matter, the gravity of which could be discerned, but whose luminescence was not apparent? Then again, perhaps it is a matter that the guardian of these images, their comptroller, was reticent to divulge their value. The suspect in me errs in this direction. Nevertheless, without further hesitation, let me enter upon what I think has been going on. After Buffalo Springfield: “there’s something happening here / what it is ain’t exactly clear / there’s a man with a gun over there / telling me I’ve got to beware”; in other words a system of policing has been in place for some time, regarding Monk’s fate, a system endemic not only to apartheid but its aftermath, post-apartheid, and what, today, I term South Africa’s phantom democracy.

But let’s return to the late ’80s, 1987 to be precise, when J.M. Coetzee publishes his “Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech”, a speech putatively on behalf of freedom, a freedom which Coetzee conceives as improbable, unfounded, absurd, given that the very freedom courted is chimerical. For Coetzee, the root of the problem is “a failure of love”. “To be blunt”, he adds, the love of the hereditary masters of South Africa “has not been enough since they arrived on the continent; furthermore, their talk, their excessive talk, about how they love South Africa has consistently been directed toward the land … toward what is least likely to respond to love: mountains and deserts, birds and animals and flowers.”

What is patently absent here is that which is central to this gathering, the human: “The Ethics and Poetics of Photographic Depictions of People.” What is it that makes it so difficult in South Africa to depict people? More specifically, why is it that in the depiction of people – and here I’m speaking of a hybrid racial and cultural configuration – have South African photographers chosen an equivalent abstraction affixed to representations of land, birds, or animals? Why, in the vaunted attempt to capture the singularity of personhood, have the images of people devolved into the symbolic, iconic, distanced; or the ruses of otherness or sameness?

The Catacombs, 3 March 1968 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

For Coetzee the answer lies in a failure of love: the intrinsic lovelessness of South Africa’s optic. Coetzee damagingly goes on to explain the sleight of hand of the reform movement, whose call for fraternity bypasses the criticality of liberty and equality. For Coetzee, this is because “the vain and essentially sentimental yearning that expresses itself in the reform movement … is a yearning to have fraternity without paying for it”. That Coetzee has been proven correct on this matter is not my point. Rather, my point concerns what Coetzee terms the “pathological attachments” which have shaped systems of oppression and resistance. It is “the crudity of life in South Africa”, he declares, “the naked force of its appeals, not only at the physical level but at the moral level too, its callousness and its brutalities, its hungers and its rages, its greed and its lies, [that] make it as irresistible as it is unlovable”.

The Catacombs, 1967 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

What I wish to draw your attention to is the perceptual register – intrinsically negative, pathologically optical – which has informed, and continues to inform, the way in which South Africa’s stories, and its image repertoire, has been recorded and received. A perversely mutinous denial of love, a pathological fascination with lovelessness, has informed the making and consumption of South Africa’s photographic archive, and I say this in the full knowledge of claims to the contrary.

Therefore, to state that South African photography remains over-determined by the legacies of colonialism and apartheid is, frankly, an understatement. Such has been the punitive hold which these interlinked systems have maintained over the South African imaginary, it is impossible not to acknowledge the degree to which these systems, and their current variants, have scarred, infected, and critically shaped the photography unleashed because of, or in spite of, these systems. Reactive in affect, moral and/or polemical in content, South African photography serves as an archive for the very illness which informs and drives it.

Distinguished by the pathological, South African photography has never truly embraced a world that exists outside of this toxic mainframe. This failure, which Coetzee notes in South African literature and not its photography, which is my concern here, harbours a longing “to quit a world of pathological attachments and abstract forces, of anger and violence”, a longing to “take up residence in a world where a living play of feelings and ideas is possible, a world where we truly have an occupation”.

Here lies the key to this debate: What does it mean to speak of a true occupation? Can one speak these days of truth? Given the currency of the simulacral, it hardly seems likely. Yet Coetzee’s goad remains critical: what is South Africa’s photographic occupation? My goad is that there is no occupation outside of the lovelessness which has informed, arranged, and sold South Africa as pathology.

I should note here that Coetzee recognises his complicity in this failure; that despite his recognition of lovelessness as key to the writing and imaging of South Africa’s story, an aporia or annulus exists: a failure, in other words, to capture the wellness of being human. And yet, Coetzee recognises, we long for such a moment of insight, access, indeed, sublimity. Frantz Fanon termed this moment “a zone of occult instability”, while Homi Bhabha describes it as a moment beyond “the sententious or the exegetical … the hybrid moment outside the sentence – not quite experience, not yet concept; part dream, part analysis; neither signifier nor signified.”

In achieving this fleeting yet critical moment we arrive at what Coetzee deems the true occupation of the arts. Other than Billy Monk only one other South African photographer immediately comes to mind, and that is Santu Mofokeng. I am not of course asserting that these are the only photographers who, according to Coetzee and Bhabha’s schema, achieve this. Rather, I’m proffering a goad; asking that we think about how and to what ends the ethics and the poetics of the human figure is captured. That Monk and Mofokeng are utterly different in their concerns and focus is another matter; yet what strikes me is that both succeed in their attempts to restore a “true” occupation to the matter of photography.

It is here that I return to the core of my rumination: That South African art, art that stems from South Africa - be it its literature, its plastic arts, or broadly, its image repertoire – persists, rather like the housekeeper in Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (the black and white Lutheran half of that film) in scratching the putrescent sore in its palm; or, if not conscious of this miserable act, it exists as the art of sleepwalkers. In other words, South Africa’s art remains loveless, incapable of “a living play of feelings and ideas”, and as a consequence, exists as an art without a true occupation.

While vast, disputable and absurd, this claim must remain my point of engagement. However, my interest is not to rehash views which I've played out elsewhere. Rather, what compels me is why Billy Monk's photos bypass this gulag of fixations. That Monk depicts an illicit world in the very moment of apartheid is not the point. As Foucault, Blanchot, Deleuze and others have reminded us, the illicit has always proved the foil for the normative: the inside requires an outside if a system of regulation and policing can produce itself.

Of course Monk, like the patrons of Les Catacombs – a telling tag – were surely aware that the roles they occupied, primarily as punters and consumers of monetarily driven sexual exchange, or other forms of illicit pleasure, were as rigged as any other privative or racially over-determined system. The glaring binarity is evident in the image of a policeman engaging the attention of a dwarf at Les Catacombs. Then again, it is the comic absurdity of that image that serves as its tell: Monk was no Diane Arbus or Roger Ballen, riveted to and mortified by the freakish, odd, or strange. Rather, this seemingly odd image, with its weighted reminder that the abnormal and the normal, illicit and policed, were in fact on thoroughly familiar terms, surely compels us to reconsider what in fact Monk was doing.

There is, I feel, no disputing the beauty of the instant framed, the presencing of his subjects within the fragmented makeshift places in which they are caught. One looks not only at the people imaged - their expressions, couture and self-stylisation. Rather, one is as aware of the dishevelment of each of these aspects. The environment, like the figures captured, are caught in a moment of wear and tear that defies the iconic and its Apollonian pretensions, giving us, rather, a Dionysian dance with the distensions, fallibilities, tenderness, hunger, longing and exhaustion, that come from being driven and informed by what T.S. Eliot called the butt-ends of our days and ways. Excessive and supplementary, they are images caught in a moment Lin Sampson terms the “cutting edge”, a moment as easily excisable as it is containable. If they defy what Sampson terms flab, space, pretension, it is because they defy received systems of perception: how a subject should look, should be framed.

The Catacombs, 1968 (Copyright Estate of Billy Monk, courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg)

It is perhaps that moment, when the excessive meets the ordinary, which gives Monk’s images their potency. They manifest ordinariness irreducible to the chic dicta of the banal; an ordinariness of life caught in a binged dissipation, a release from the constraints of an overly conscious – indeed monstrous - self-possession. That said, it is not blind drunkenness and debauchery and, after Rimbaud, the wild derangement of the senses, that Monk captures. Rather, it is that moment, neither epic nor tragic – a moment Brecht sought to still, the better to reflect upon it, the better to graft upon it his particular political spin – which returns us again and again to the rollicking tenderness of the incidentality of Monk’s images.

There are no big pictures here, no portentous freezing of a moment, no narrative overdrive which could explain the artist’s oeuvre. As snap-shots Monk’s graphic depictions, like the series by Richard Billingham, titled Ray’s a Laugh, are not shut-up the better to secure a certain sanctified closure and ethical legitimacy. Of Billingham’s glaring disclosure of his parents lives Gordon Burn notes: “It is a brilliant [photographic] essay on the psychopathology of family life which is also brave enough to suggest that destitution – more: squalor and degradation – can produce images that are not only not ugly, but actually galvanising and beautiful.” If Monk’s photos, like Billingham’s, are not shut-up or closed off, the better to engender a critically consensual moral approval, it is because, in the instances of dissolution he captures, there is also something naked, celebratory, fulsome, positive: loving. It is this fullness of heart which makes Monk, after Baudelaire, the photographer of modern life.

For Baudelaire, the painter of modern life was Eugene Delacroix, who Baudelaire described as “a strange mixture of scepticism, courtesy, dandyism, fiery will, guile, despotism, and, withal, of a species of particular kindness and restrained tenderness that always accompanies genius”. These qualities, I feel, apply to Monk. In reading Lin Sampson’s texts on Monk one arrives at a comparably complex conclusion.

I am not asserting that Monk is Delacroix. Rather, in signalling a link in temperament, and a way of seeing and feeling such a temperament could generate, I’m asking that we consider Monk as an anomaly, disinvested yet connected, for good reason. Sampson notes of Monk’s photographs: “There was some sense of artistry beyond that of the average nightclub photographer – or was there?” The qualification is crucial, for Sampson is not interested in setting Monk apart. Rather, she locates him within the moment he captures, for given the complexity of his temperament, it is the recorded instant which the temperament reveals – in which that temperament discovers itself – that matters the more. For Sampson that temperament, emphatically, alerts us to worlds which exist beyond codes.

After Nietzsche, one could say that Monk’s photographs are untimely: subject to their time yet bizarrely outside of their time. That Monk’s photographs possess the appeal which they do today is in no way merely because they were anomalies then – they remain anomalies now. Irrepressibly present, immanent, Monk’s photos never objectify their subjects, never reduce them to emblems, symbols, or symptoms of some gnomic deep structure.

If his subjects are neither revealed nor hidden this is because they resist the sententious and exegetical. Archibald McCleish noted that a poem should be, not mean. I think it is the beingness of Monk’s photos which stays with one. They exist in and for themselves, and, so doing, make no claim to the fullness of a present or the nagging lack that is absence. Neither objective nor nostalgic, neither reflexive nor coolly matt, Monk’s photographs challenge not only the limits of the technology which produced them but the codes to which criticality might reduce them.

If Monk’s photos are gaining a wider appeal today I would hope that this is not because of their technical finish, framing, retro culture and style; their disturbingly cool perpetual presence; or their scandalous subversion of the oppressiveness of South Africa’s policed culture at the time. Rather, I would hope that what a viewer is compelled by is their radical immediacy, honesty, and effortless disregard for the very scopophilic drive which infects all acts of seeing and all acts undergone in order to be seen. The phenomenological is a register and optic I’d apply to Monk’s photos: they see without wishing to probe; record without the cool distance one associates with the document and the documentary. Which raises the question: what is it that makes Billy Monk distinctive and staggeringly rare?

Others have reflected upon this question before me, notably Lin Sampson, Michael Godby, and Sean O’Toole. Others, still, will emerge to refine what remains a piecemeal critical perspective. For what is immediately apparent is the paucity of critical response: not enough has been written and thought about Billy Monk. The Michael Stevenson Gallery is preparing a monograph as I write, which I hope will open up the debate and explain the scandalous riddle of Monk’s absent presence in the South African cultural imaginary.

My wager is that Monk continues to function as a lacuna in the symbolic order that over-determines South African aesthetics; that unlike most he escapes this over-determined system because he captures the wellness of being human in a time – then and now – which photography has largely failed to capture. Further, he does so because his photos are never shaped in a manner that wholly encodes them: Monk is no Mannerist. Caught in a mortal coil his figures are never raced; sexed, yes, but raced – not quite. Contra the broad spectrum of South African photography over the last 30 years, Monk’s images return us to a living play of feelings and ideas which for far too long has been suppressed in the instant of their acknowledgement – only to be deferred.

References

Baudelaire, Charles. The Painter of Modern Life. Trans. P.E. Charvet. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London & New York: Routledge, 1994.

Burn, Gordon. “Richard Billingham,” in Sex & Violence, Death & Silence. London: Faber & Faber, 2009.

Coetzee J.M. “Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech,” in Doubling the Point. Ed.David Attwell. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Garb, Tamar. Figures & Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography. London: V&A Publishing, 2011.

Sampson, Lin. “Now You’ve Gone ‘n Killed me,” in Mahala 2. Ed and published by Andy Davis, 2011.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

I am so pleased to see Billy’s work online, Billy was a special person, I met him in early 69. He was a lovely, sensitive and caring man. Thank you for showing his wonderful work.

Dr. Jamal’s receptive and caring engagement with Billy Monk’s photographs exceeds the usual limits with which many commentators attempt to define, say, the Japanese Bara (1960s) or, say, Jim “Flash” Metiff’s photographs of American bikers from that same decade. Monk, too, exceeds the load of the documentary and gives us pause to reconsider academia’s nostalgia for subversive; Monk’s genius, then, in Jamal’s relocation of his work, is indeed the incidental so sparingly revealed on film in the photograp of the dwarf and the Officer.

Great stuff, Ashraf! This signals only the beginning of a project on all fronts, including literature, to recover work that was wholly neglected by the “gulag of fixations”, a gulag buttressed by various forms of exclusion and manipulation of critical “acclaim”. Who will start this bigger project? Who will have the courage?