Videos

Latest Translations

by Bongo Khwelo Flepu

by Chantelle Gray van Heerden

Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Nobel Prize for Literature: Read Tina Steiner in ‘The Conversation’

Posted in Blogs

Leave a comment

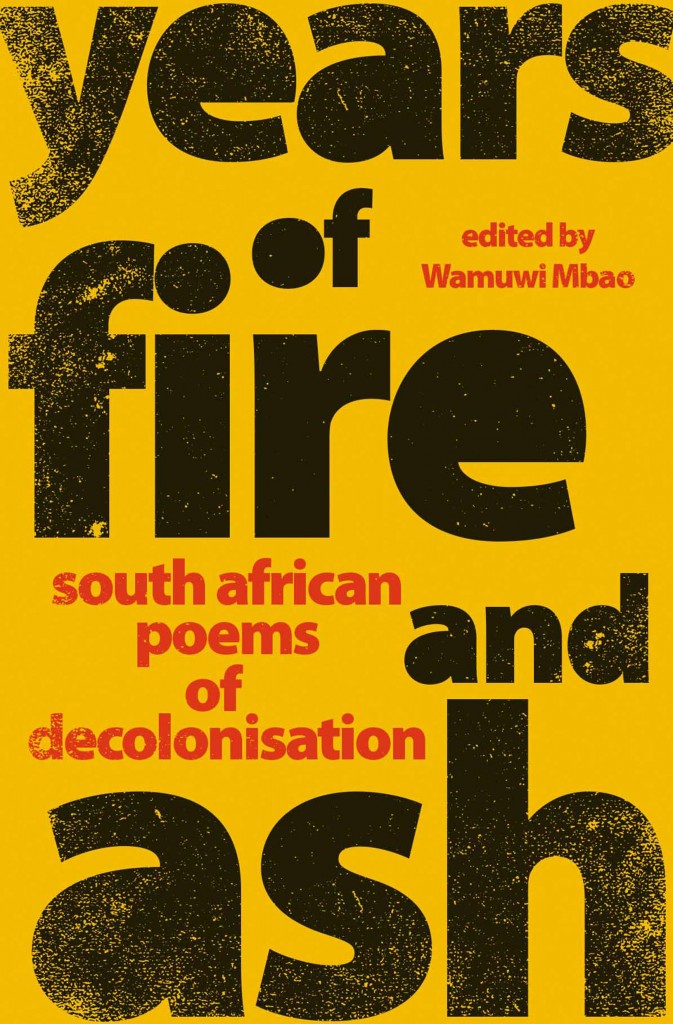

“What happens after the fire?” Years of Fire and Ash: an interview with Wamuwi Mbao

Nadia

Perhaps a good place to start would be the title. It's a very powerful title, Years of Fire and Ash: South African poems of decolonisation. It brings to the fore ideas of burning with all sorts of historical political connotations, and then after reading your introduction to the collection, there seems to be this disappointing sense of returning to ash. Why this title? Where does it emerge from?

Wamuwi

Well, it is actually from a poem by Oupa Thando Mthumkulu, called “Nineteen-Seventy Six.” But I think it came out of this idea that when we were putting the collection together, you know, we were trying to think about what are the lines of commonality between this stuff that we tend to consider as struggle poetry. And the current era of political poetry that comes out of movements like Fees Must Fall and the struggles for free education and things like that. And I think as we worked on it, it began to resonate more and more, because, you know, they were all of these points of commonality that came up especially around ideas of fire and burning. I mean, remember when artworks were being torched at UCT, and how that was one of those kind of galvanizing images and moments. And I thought, well, you know, it's an interesting image to come back to: what happens after the fire? What happens after these moments? Because, of course I think that this was also one of the kind of undergirding ideas with this collection, you know. We don't want these significant poetic moments to disappear when the fire has gone out, as soon as things have kind of calmed down a bit. So I think that's really as much as it says, as we thought about it.

Nadia

You speak in the 'we'. You speak as a collective, represent a collective. And one question I want to ask you - because I've been thinking about this idea of how there's a long history to this in academia - around writing as an individual, and being the sole holder and producer of knowledge, and then writing as a collective or a community, and how the latter means of producing knowledge is often subjugated and seen as secondary to being a sole creator of knowledge. Why was producing knowledge in this collective way important to you?

Wamuwi

I'm always wary of being in a curative role: when you're the curator, you get the banner head name on the collection. Now, that's a little bit misleading, because it doesn't really show all of the meetings and the consultation and the collaborative work that's gone into this and especially because when I started on this project, I had a meeting at Jonathan Ball, and the idea came together collaboratively from there. And while I was placed in a sort of curative role, when it came to working with a lot of the more contemporary poets, especially, I immediately began to see that this isn't going to work, if it's just me harvesting things and putting my own spin on it, you know, so I began to engage with the poets and say, "Okay, but what kind of collection do you think we need to be putting out into the world? Who should we be including, who should we be looking for?" And it really then began to take shape as a collaborative process in that way. I feel that this is something which really gave it it's strength; the fact that, even if it is my name on the front, the kind of work that went into it and the conversations that went on, means it was it was a group project, and that gave it a chance, because it took it to places that I hadn't considered. I think I have a fairly good reach where poetry circles are concerned, but there are a lot of people I haven't come across and I would have my own biases in those terms. And getting beyond that was really quite important. You're always self-conscious as an academic of not projecting your own very narrow reading on things. So being able to speak to, and work with, people who could then say, "Hey, look at this person", or "Why didn't you talk to them?" really helped in that regard.

Nadia

And obviously, one cannot choose every single poem that speaks about, or to, decolonisation over this time period – 20th century to the second decade of the 21st century. And you do speak about that in the introduction to the collection. You carefully lay out that certain editorial decisions had to be made around what goes in and what you have to leave out. But of course, we know that there's a lot more work that someone else has to take up at a different time in a different collection. And the choices are magnificent. I like the way that you've conceptualised decolonization as this necessarily incomplete, shifting, uncomfortable, unsettling movement and process. So it's always moving rather than something concrete. And of course that is central to, I think, how the poems are read. One needs to move from the position that decolonisation is not this one moment that will eventually come to an end; this is a moving moment. And what struck me very deeply is this idea of anxiety that is produced through what you've called "structural disorder". You talk about how poetry, in general, is useful in terms of thinking through and conversing with this idea of anxiety, this South African emotional mood of anxiety. So, I want you to talk a little bit more about that - this connection between what you call the present sense of anxiety and the decolonial poetry in the book.

Wamuwi

Yeah, I think that as I was going through the terms and finding the poems and talking to a lot of the poets about what kind of mind space they were in when they were writing and putting it together, something which came to me again and again was always this idea that there is no way to close off a period and say, you know, "okay, decolonization is from this time to this time, and it began here and it stops here." And, of course, you're always running after this sense of thinking that this could be a 1000 poem collection, if you really wanted to try and harvest everything, and you still wouldn't have gotten anything more than a small sample of whatever else. And so very early on I realised that we needed to think about it in terms of how poetry itself works, which isn't about closed boxes and things that come to an end; it's something which is ongoing, and it's not about the easy solutions. And so in terms of this process of - especially writing through anxiety - what I realised is that after you reach this period of time, especially with the poetry of the 2000s, if you want to call it that, where, in addition to these centralised topics, what is actually energising them, and giving them the sense of activity is this undergirding mood of, “well, we have achieved democracy, but things are not quite as we want them to be,” and there are a lot of other feelings that begin to take place. So if you think about the early poems often being cauterised by the major mood of apartheid, after 1994, you see this shift of people trying to talk about what might have been termed minor feelings, things that we didn't really have a vocabulary for; we didn't really know how to speak about this being important to us, you know. I think that poetry, in some way, helps people to get at those more minor feelings, because it allows you to learn, as we often very rarely talk about how the personal and the political can be deeply affecting; it allows you, as a reader, to take your own particular kernel of meaning from it, and in very interesting ways. And I think that the more we went on, and the more poets I engaged with, what came up again and again for a lot of them, was that anxiety was kind of their dominant framework for relating to the present; this idea that so many of the aspects of society that matter to us, occur through this framework of worry. You worry if you have enough money for your tuition; you worry about violence of various kinds in the world, whether it be particular to you or happening in close proximity to you and things like that. And reading this anxiety, I started thinking that this isn't something that is only about the present, it actually goes back. Like when you read, say, "Always a Suspect" by Oswald Mtshali, you've got that sense of anxiety coming through as well. That's a poem that is traditionally only ever read in that kind of Soweto poetry framework. But actually, there's a lot more going on there in terms of what the psychic effect is on you as a person, of living in a society that treats you this way, that relates to you in a particular way. And so that's, I think, the thing that really began to take hold as the collection grew and took on a particular structure. It was about how these different and very diverse kind of mood generate the same kind of affect in the people who experienced them, the people who write about them. There's so much more to be to be said about that. As I was writing the introduction, I was thinking that there's so much scope for a slightly larger kind of academic volume, but at the same time, I don't always necessarily know if that's the best output for these things. So I think that what we put together here gets at the atmosphere of the present in a way which has maybe wider currency for a lot of people.

Nadia

This engagement with anxiety is an interesting one. You speak about the psychic effects of living in a particular society; how those effects have and haven't changed, and the similarities and divergences in what you call the "same poetics of resistance across a collection of poems". I am thinking about how the multiple temporal realities brought about through the combining of decolonial poetry, from the mid 20th century to now, offers us a trajectory of sorts of poetic resistance of structures, systems that continue to perpetuate injustice and injury. The kind of bite-sizedness of poetic narrative makes it quite easy to read. For me, it's often a mood, and the feeling that it elicits, rather than trying to analyse it line by line, because that is not, I think, what the purpose of poetry is. So I want to ask you a question about what you think these poetry narratives do? What do they do within this process of decolonization?

Wamuwi

I think that's one of the things that I often struggle with - and I think a lot of people tend to as well: if you went to school, and you learned about poetry in a particular kind of way, then I think it either is something that you click with in a particular way, or it generates a block that stays with you forever. And I think I fell into the latter category, where, as soon as I see stanzas of neat writing lines and things, I go, "Oh, it's a poem!" I don't know what this is meant to mean, and that anxiety immediately sits with me. And I think I began to think about ways of getting beyond my own block with this collection. That was part of the reason why I took on the task, you know, because I was someone who came to poetry with that kind of hangover of like, "Ohhhh, poetry". And thinking then about what it is that that poetry does. What is the active kind of work of this kind of lyric output, because poetry can be so many kinds of thing; in this particular format, it becomes a printed thing. That's just one output or one form that poetry can take. And so it meant engaging with the idea of what is it that poetry has historically done in society. Why is it that certain kinds of poem stay with us in a particular way? And especially when you think about some of the earlier kinds of poem that fall into this collection, and some of which are not in this collection, by people like Serote, or if you think about a poem like "Africa, my Africa", things which people who would never, ever consider themselves particularly interested in, throw off a line here or there, because it somehow embeds itself in the consciousness in a particular way. I think that's something which I began to be very interested in tracing because there is something in the way that a particular kind or genre of poem is delivered or in the way that it expresses a particular source of truth, that sits with you in a particular way and that way might be entirely personal and subjective. But then trying to trace what is in that experience of poetry; what is it about? What happens in that moment that we carry away with us, began to be something of high interest to me. One of the things that I actually enjoyed about this collection was that, even though the publisher was quite insistent - and we had quite a strong back and forth about whether to have things in chronological or non-chronological order, and they won out eventually – I did intend it to be something that you could kind of get into at any point because that also then changes the way the poems work in conversation with one another. So rather than reading it from front to back - you can do that - if you jump outside of that kind of ideological timeline, then it creates interesting storylines, like what is it about this or that older poem that we hear echoing in a poem from forty years later? And it always comes down to, for me, because people have such different understandings of what poetry constitutes, "What is poetry to you?", you get ten different answers to that question. Poetry is not something that has a particular and exact form. But it definitely has a particular kind of affect. You know it is poetry because you experience it in a particular way. And that's the thing, that elusive thing, which you are trying to get a handle on or looking to, when you put a collection like this together.

Nadia

Yes, what does any writing do? We know what it does, because we, we feel a response, I think, whether it's poetry, or more kind of academic forms of writing. I don't know if it is, should it be? Should we call it completely creative? I don't know. What we know for sure is that it's political.

Wamuwi

On the one hand, you're dealing with a lot of poetry, especially with some of the earlier poems that we were putting together here, which was created with a very strong purpose of mind, poetry that meant to energise people in a particular way. For instance, a lot of the poetry is meant to be performed. But then, I'm taking it and saying ‘but outside of that immediate context, what else does it do?’ I think nowadays we tend to be very uncomfortable with the idea of forcing art to have a particular purpose. That's always the thing that you kick against. Like, beyond its kind of prescriptive role, what else does it do? And the 'else' is actually the interesting thing, because beyond that, how do you read, for instance, Serote, in our context? What is he saying that we might derive any kind of meaning from? And it's a very vexing question, which doesn't have any kind of easy solutions.

Nadia

When you wrote your introduction, who were you writing for? Did you have an intended audience?

Wamuwi

I think that I had to keep in mind that it was for a collection. And of course, it was helpful that, from the get go, as you said, we don't necessarily think about an intended audience in a very strictly defined way. But, of course, the publisher does because they need to sell books, and so the question of what sort of direction you want to take becomes important. And I think when I was writing the introduction, I had in mind Makhosazana Xaba, who said at a conference once that she thinks about making work legible for her mother or her grandmother, or someone who is not necessarily in the academy, but who is not an idiot. The reader that you have in mind is someone who might not necessarily work within those very kind of specialised frameworks of knowledge that we occupy, but who might be very interested in understanding what these concepts are. So for me, it was about taking a term like decolonisation and moving it out of the academic space, because we all remember when this term began to be bounced around in a local context, and there are all of those news clips, with people ridiculing students for talking about science and maths needing to be decolonised. I think of a moment like that and you see that the ridicule is coming out of people not understanding what this term means, or how it might have application beyond a very localised set of languages. So then when you write an introduction for something like this, you think that you’re not just talking to academics, and in that regard, it was also helpful that because the poems came from so many diverse voices - some of the poets are academics, and some of the poets are performance poets, people who go on stage and recite their poetry and do things in very different kinds of contexts. And all of them have very different, but overlapping audiences, people who are interested in poetry and the workings of it. And I think that's how you then start shaping an idea of your audience; you start thinking that this is a text which should be something that someone can pick up in a bookstore, someone who might be interested in the book, they might like the cover and go, "Oh, what's that?" and then not feel alienated by it. And then similarly, a text which might have application in spaces like the university. One always thinks that you have to keep an eye towards whether this is something that could potentially be prescribed or, taught in a course: those are always your practical considerations. But you try not to let them over inform how you put this together, because of course, then you end up writing a textbook. And there's a broader world out there.

Wamuwi Mbao is a writer and essayist. He reviews fiction for the Johannesburg Review of Books. He lectures at the University of Stellenbosch, where he is based in the English Department. His short fiction has been published in various anthologies.

The steel structure on the corner of Merriman and Bird street

Although this place was created for me and people like me, I was once scared of walking here alone. I was 17 when I first took a Taxi all by myself. I had done this once before, but I was about eight years old and my mother was with me. The day I took the Taxi alone, I was in my high school uniform, a so-called Model C school and I remember sitting in the Taxi with a few kids from the secondary school down the road from where I lived. It felt like I stood out and my confusion and shyness did not help me it just highlighted the fact that I was not familiar with Taxi-etiquette, but like the kids from the secondary school I also needed public transport.

Taxi-etiquette

So, let me tell you something about the Stellenbosch Taxi-etiquette, the Taxi driver can pick-up two to four more passengers than the amount that they can carry. In other words, ignore the big sign that says: “certified to carry up to 16 passengers”. Secondly if you’re petite or just skinnier than the rest of the people in the Taxi, you will be expected to sit in the most uncomfortable places or to stand in the passage, but you are more likely to be squeezed into a tight space. Thirdly, do not pay with a R50 or R100 early in the morning. The taxi gaatjie (guard) or sliding-door-operator, as they like to call themselves, will look annoyed and you might end up with 40 one rands for change. There is no room for shy, sturvy people in a taxi. You will be drawn into random people’s conversations and you will sit next to a drunk person who smells like cheap wine at least once a week. Lastly, we all notice the odd ones out and the passengers in the Taxi can have a coded conversation without the “odd one” noticing it. There are a few more favors that we as regular customers get to access, like being picked up at your doorstep, having a seat reserved for you and so on.

The Stellenbosch Taxi rank and the surrounding area.

I always had my phone in a little sling bag and when I got out of the Taxi I clinged onto my bag a little tighter, speed-walking and avoiding eye-contact with most people. Ignoring catcalls and getting away from that area in town was my only mission.

The Taxi rank is a crowded place, with up to 300 Taxis who can carry 16 passengers each (or even 20), so if all of them only drove twice a day there would be at least 9600 people passing through the Taxi rank per day. The Taxi rank became a prime economic center and thus we have so many informal brokers and even bigger franchises like King Pie, Romans and a variety of other businesses, who use the Taxi Rank to sell or advertise their products and services by handing out pamphlets and freebies. The area around the Taxi rank is also created for the taxi passenger, who is most likely a working class or middle-class citizen without private transport. The shops around the Taxi rank are low cost shops, starting on the opposite corner of Bird street and Merriman avenue there is a wholesaler, who sells things for quite cheap; a Chinese clothing store; a relatively cheap fast food restaurant; Choice clothing, a clothing store that sells the factory faults or reject clothing from other brands; there is a Pep, another cheap clothing store and then there is a Britos, a cheap meat shop. Then when you cross the road at the intersection by Crozier and Bird street you head to Jet an affordable clothing store and directly opposite jet you will find a bottle store, this explains why there is always drunk people at the Taxi rank.

The odd one out

When I was without my school uniform on, I blended in a bit more, because then I was just a colored girl and my privilege was not written all over my body. To explain this, I want to tell a story of two other girls in my school, Jade and Cara. Jade and Cara once took the Taxi with me, also in school uniform and because Cara was a white girl, when she got into the Taxi, no one really said something, but everyone just stopped and stared. This day I was not the odd one out anymore, nor was Jade, because Cara had more differences. The Taxi rank was created for everyone who need the Taxi services, but some people just stand out more than others.

Posted in Blogs

Leave a comment

The wanderings of a lonely sojourner in quiet suburbia

By Tendani Tshauambea

It’s just gone 4pm, with the maddening heat of the Highveld a little more tempered than earlier, I decide that it is as good a time as any to go for a walk around the neighbourhood. Having been cooped up inside the house since I arrived in Joburg three days ago.

As I leave the house through the kitchen door, I emerge onto the driveway, our cul-de-sac to my right (where Nandi from number 4 — opposite and two houses to the right — organised a street braai that one time) , I turn left onto Mount Boreas and immediately pass Mr Khumalo from number 8, diagonally across from our house. He is busy taking in his refuse trolley while speaking animatedly on the phone (no doubt closing a business deal). He nods his head in greeting and I raise my hand, uttering a feeble Unjani Baba as I trod along the street.

At the corner of Mount Boreas and Mount Shovano, I turn left and walk a short distance until reaching the junction between Mount Shovano and Mount Wakely. Turning left onto Mount Wakely at the end of Shovano, I make my way along a street that, in a few houses, characterises the neighbourhood. Sprawling driveways (accessorised with all manner of premium cars), well-manicured lawns, immaculate landscaping. The quiet scene is broken only by the constant chirping of birds in the background (the screaming kids being confined, thankfully, to the many parks dotted around the neighbourhood). The collection of flowers on some of these forecourts would rival any half-serious botanical garden. I turn left onto Mount Augusta Drive, the main road running through the neighbourhood.

On Mount Augusta Drive, I pass all manner of workers: house staff, butlers, horticulturalists, groundsmen (who keep the gardens along Mount Augusta Drive looking immaculate) as well as the army of the (mostly) men in navy blue who ensure that residents can ‘live, learn and play (safely)’, the motto of Midstream Estates, in a sort of ‘separate peace’. Each time before I pass one of these staff members, I agonise over whether or not to greet and whether I do it in IsiZulu, Setswana or Tshivenda sans my former model C school accent, of course. Oftentimes settling on busying myself on my phone. It’s only after noticing a few more people than usual on a stroll through the neighbourhood (and my continued agonising over greeting boUncle and boMama), do I realise it’s knock-off time.

This is confirmed by the hubbub of workers from the many houses walking, cycling and being driven to the gate by their employers or on the neighbourhood minibus (‘donated’ by one of the residents as their own personal form of corporate social investment). This flurry of activity breaking through the faint sound of chirping birds and cacophony of cars going to and fro.

As I walk along this road, I notice a sense of camaraderie, familiarity, perhaps even a sense of community amongst the staff walking past each other and in groups towards the gate. This Which comes across in the greetings, stops for a quick chat, the sharing of a joke or the day’s happenings. As I near the end of my walk by the gate (the end of Mount Augusta Drive) where many of the people I saw end one journey and begin another (the homeward journey by bus, taxi or bicycle, for those fit enough to do so), I realise something. This sense of community I witnessed eludes me. Not by virtue of not partaking but because I do not belong to that group of indispensable sojourners of this community. Instead, I am relegated to continue my wanderings as a lonely sojourner. The collection of flowers on some of these forecourts would rival any half-serious botanical garden. I turn left onto Mount Augusta Drive, the main road running through the neighbourhood.

On Mount Augusta Drive, I pass all manner of workers: house staff, butlers, horticulturalists, groundsmen (who keep the gardens along Mount Augusta Drive looking immaculate) as well as the army of the (mostly) men in navy blue who ensure that residents can ‘live, learn and play (safely)’, the motto of Midstream Estates, in a sort of ‘separate peace’. Each time before I pass one of these staff members, I agonise over whether or not to greet and whether I do it in IsiZulu, Setswana or Tshivenda sans my former model C school accent, of course. Oftentimes settling on busying myself on my phone. It’s only after noticing a few more people than usual on a stroll through the neighbourhood (and my continued agonising over greeting boUncle and boMama), do I realise it’s knock-off time.

This is confirmed by the hubbub of workers from the many houses walking, cycling and being driven to the gate by their employers or on the neighbourhood minibus (‘donated’ by one of the residents as their own personal form of corporate social investment). This flurry of activity breaking through the faint sound of chirping birds and cacophony of cars going to and fro.

As I walk along this road, I notice a sense of camaraderie, familiarity, perhaps even a sense of community amongst the staff walking past each other and in groups towards the gate. This Which comes across in the greetings, stops for a quick chat, the sharing of a joke or the day’s happenings. As I near the end of my walk by the gate (the end of Mount Augusta Drive) where many of the people I saw end one journey and begin another (the homeward journey by bus, taxi or bicycle, for those fit enough to do so), I realise something. This sense of community I witnessed eludes me. Not by virtue of not partaking but because I do not belong to that group of indispensable sojourners of this community. Instead, I am relegated to continue my wanderings as a lonely sojourner.

And Wrote My Story Anyway, Barbara Boswell

Book Launch Response, Dr. Mandisa Haarhoff

What is it to “forcefully create” oneself? To “foresee the future through writing”? To “create new worlds our of nothing?” What is it to be transgressive as a Black South African Woman”? To “write your story anyway”? Barbara Boswell’s And Wrote my Story Anyway ‘lays bare’ or ‘makes visible’ in the [Jamesonian sense] the works of black women whose literary production has been ignored by androcentric and racist critical traditions in South African literature.” She details in the span of six body chapters, her authors note, introduction, and conclusion the multiple ways in which black women writers, like Bessie Head, forcefully created themselves under the extreme conditions of being black and woman in South Africa. This creating takes the vast, intimate, often incommunicable experience of being a black woman and turns it into theoretical grammar. Drawing on Carole Boyce Davies’ notion of ‘migratory subjectivity,’ for Boswell, “black women’s writing signals personal agency, since the act of writing, for a black woman, consists of a series of boundary-crossings requiring an active agent to do such crossing” (4). In this book, Boswell maps these boundary-crossings, engaging the ways in which black women’s writing invites us to rethink the geographical, national, racial, patriarchal, and even aesthetic strictures.

Boswell is not concerned with considering black women’s writing within the scope of black male and white writing that is centered as South African literature, and rather traces the terrain of black women’s writing in their own aesthetic and theoretical terms. Boswell takes these women writers in their own words and articulates for us the literary topography their works make possible. Through this book, she carves a genealogy of black women’s writing, specifically in the form of the novel, and the aesthetic and theoretical grounds for feminist thinking that these texts provide.

Through pointed closed reading, Boswell describes how these Black women writers tend toward their blackness as generative grounds for imagining, revealing, speaking womanhood in Southern Africa. To tend to blackness in these texts, and through the theorizing analysis Boswell offers, is to consider the critical and feminist possibilities of subversion, borderlessness, incoherence, of spectacle, of refusal, of being elusive, fractured, abstracted, ambiguous, slipping through the bounds of reasonableness and respectability, without category, writing into the fissures, forced silences, and devised gaps, insisting on much more than mere survival in the nationalist, racist, and androcentric world which can only marginally include women. To determine their narrative in the literary landscape and women’s lives in literary imagining these writers forcefully engage their identities as marked, threatening, and incommensurable. They escape the critical markers of aesthetic acceptance by both Black male and white critics precisely for the reasons that defines their black womanhood. Their writing settles into otherness—privileged by neither race nor gender-- as queer feminist praxis, fractured existence as refusal of racist and patriarchal hierarchical taxonomy. They do not offer their characters attainable escape from the strictures which contextualize their lives and rather offer the world of these characters as grammar for worlding outside of nationalist, white and male centered human rights, and formulaic aesthetic codes. They offer no neat conclusions, progressivist pursuits, or even transcendence. To “write my story anyway” is to expose the racist, heteropatriarchal, nationalist, and androcentric ways of reading as pathogen, to bring the ghostly fleshiness of female bodies into sharp, unapologetic, and unreconstructed view.

To read black women’s writing, Boswell insists, is to bare the disruptions, consider the chaotic, lean toward the alternate, listen for the questions, be with the shadows, the wayward, attend to rupture, theorise both out of time and out of place. Boswell writes, “A black South African feminist literary theory, then, accounts for the ways in which not only colonization, but also the singularly destructive inhumanity of apartheid inflected and structured people’s lives and continues to shape collective and individual futures.”

Posted in Blogs

Leave a comment

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project