I never understood why Die Antwoord (and Jack Parow for that matter) became the poster boys for Afrikaans hip hop. Similarly, I could never grasp how the title of a group like Bittereinder could not be read for its connotations with the South African War, survival, and a culture in crisis. Most of all, I just didn’t get the subversion. The legacy of Afrikaans punk rockers Fokofpolisiekar, some might say, who opened up a different kind of questioning around the post-apartheid and how we constitute South Africa through music, are responsible. Others might say that Fokofpolisiekar are just telling the kids what they want to hear.

Listening to Doosdronk by Die Antwoord, which for the educated is a re-enactment of drunken farm violence, I found myself nauseated. Not for the reasons one might expect, or for the same reasons some are disgusted by DOOKOOM’s new work, but rather because Die Antwoord are not the subjects of the outrage that has targeted DOOKOOM. Die Antwoord’s vacuous self-parody spits in the face of a much richer, more articulate history of subversion through the Afrikaans language. What Die Antwoord do, is render farm workers as drunken cunts with violence innate to their psyche, an act more violent than DOOKOOM’s cursing of the land.

It’s not their fault. The curse has always been there. Perhaps what 1994 failed to do was to remind us, in the terms of Ashley Montagu, that ‘race is the witchcraft of our time’ and ‘the means by which we exorcise demons’.

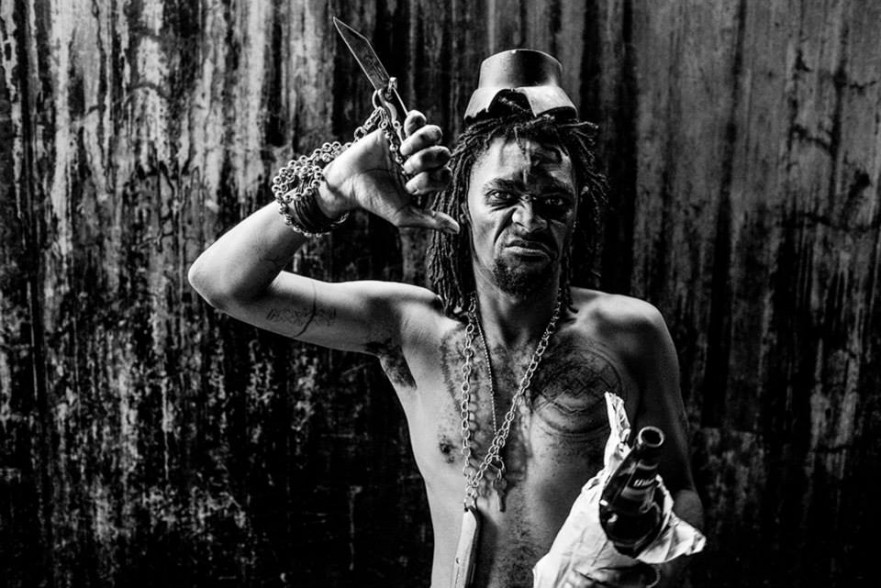

Perhaps the critiques of DOOKOOM’s work do the same, through the assertion that the video is an empty invocation, an incitement. Unrest. The language is familiar. It informs the machinery of Afriforum’s reasoning. DOOKOOM forces us to listen with a different ear, and in the video, subverts our gaze. In DOOKOOM’s line that precedes the controversial middelvinger that many (especially those who promote ‘good neighbourliness’) could not stomach, Isaac Mutant channels a history of subversion he knows and understands, a political sophistication that had at its core a need to expose, to live on the edge that is possibility.

Koes koes, daar hol hulle. A rhythm and phrase well known to those involved in marches against the apartheid state in the 1980s, DOOKOOM channels it to make powerful commentary on the complexity of the problem of farm violence. The history of subversion in South Africa is one that begs a careful listen, at full volume with your windows down and screaming ‘jou poes my lanie, jou poes my lanie, jy kan nie vir my vertel nie’. The Genuines, ghoema-punk from the 1980s, emerging alongside what has become the grand narrative of Afrikaans musical protest – Voëlvry – articulate subversion very differently on their 1986 album Goema through songs like ‘The Edge’ and ‘Struggle’, while hip hop in South Africa isat the outset Afrikaans through artists like Prophets of the City and BVK.

Perhaps the edge is the only place to be, as The Genuines put it. In the documentary film Sea Point Days, by Francois Verster, there is a moment where young so-called coloured children van ‘n klein dorpie op die platteland do an ‘item’, a musical piece, for elderly folk at a retirement home. This scene with shots of the aged enjoying the performance becomes interspersed with archive footage of people performing in what is assumed to be the well-known instances of slaves performing for their masters in the U.S.A in the late 19th century. The question, it seems, is not whether the trope is dead. The question is why it is so recognisable.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project