New Yorker writer Kathryn Boo has written a powerful indictment of slumworld inequality. What can South African readers learn from it? Everything, writes RICHARD POPLAK.

In The Road to Wigan Pier, that nightmare ramble through the slums and slag-heaps of northern England, George Orwell gathered every last cliché concerning poverty in England and ditched them like the contents of a chamber pot. He revealed a landscape and a people utterly defiled by industrialism – an underground, soot-blackened serf-class killing themselves to dig up the coal driving king and country to further glory. Nothing in Dickens or Thomas Hardy prepared readers for Orwell’s reportage. Wigan Pier still stands as the greatest piece of writing about the poor, a bible for those who hope to do the same.

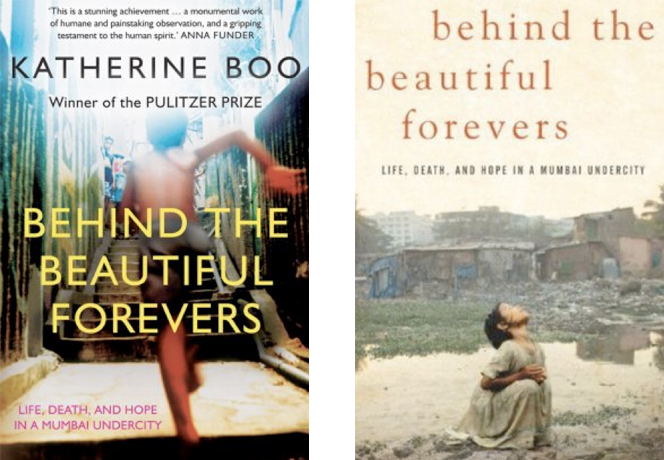

Call Kathryn Boo, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and writer, Orwell’s greatest living acolyte. She has made her career covering the disadvantaged for publications like the New Yorker, and has now turned her wry, unflinching gaze to India. Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity, her first book, tells the story of slum dwellers trapped in the cogs of India’s whirring economic machinery. Along with Wigan Pier, the work of Joseph Mitchell, and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, it takes an immediate and high-ranking spot in the poverty-writing canon.

Boo won her Pulitzer for a series of articles, published in the Washington Post, concerning that city’s failure to care for its mentally challenged. Unlike most of the reporting one is likely to read on the disadvantaged – the New York Times’ syrupy Nicolas Kristoff comes to mind – Boo is incapable of pity, paternalism or canned outrage. The series’ power resides in the meticulous collection of information, structured so that the stupidity and neglect come to seem systemic and far-reaching. Her work stands as an indictment of a system that is designed to turn even the retarded into commodities.

If this makes Boo sound like a garden-variety liberal, think again. Her writing transcends cheap left-isms or right-isms; her deep well of empathy guards her against sympathy, political or otherwise. Through Boo, we learn how brutal we truly are – not necessarily as Republicans or Democrats. But as humans.

Despite these credentials, superimposing her gestalt on India could have been a huge mistake. How does a foreigner waltz in to the world’s biggest country, one with a literary culture that doesn’t need to outsource, and survey it with a Western eye? Was this to be Boo’s Kristoff moment, 300-pages of cringe-worthy text, a chuck under the chin for the country’s 700 million slumdogs?

In focusing on one small shantytownasdcalled Annawadi, built within spitting distance of Mumbai’s glittering airport, Boo trades grandiosity for close observation. This isn’t a tome about Poverty and Caste in India, but rather the story of a desperately poor community lashed to a rising super-economy. If Annawadi does point to India at large, it’s in the following way: “As India began to prosper, old ideas about accepting the life assigned by one’s cast or one’s divinities were yielding to a belief in earthly reinvention. Annawadians now spoke of better lives casually, as if fortune were a cousin arriving on Sunday, as if the future would look nothing like the past.” Which is a dangerous way to view things when you live on the banks of a sewerage lake. Laudatory Economist special features aside, India’s boom is not without its casualties.

The book is structured like Dickens by way of John Grisham. In the opening pages, we learn that Abdul, 16-year-old-ish (“his parents were hopeless with dates”) is on the run. Fatima the One Leg, his crippled neighbour, has set herself on fire, and now he is caught in a frame-up. “Mule-brained with panic,” Abdul hides in the only place he feels safe – the shack where he keeps his scavenged trash. His livelihood, along with the welfare of his family, is built around the stuff that others throw away. Garbage is Annawadi’s coal, and Abdul is a garbage maestro. His work ethic, and his ethical outlook in general, make him something of an outcast in a community that, while no one has a Maybach on order, gets ahead by stepping on the heads of other poor people. Life in Annawadi is a zero-sum game. You win, I lose.

The nobility of the poor? Boo has no time for this. “True,” she writes, “a few residents trapped rats and frogs and fried them for dinner. A few ate the scrub grass at the sewage lake’s edge. And these individuals, miserable souls, thereby made an inestimable contribution to their neighbours. They gave those slumdwellers, like Abdul, a felt sense of their upward mobility.”

Like Orwell, who was confounded by poor people who rejected socialism despite having the most to gain from it, Beautiful Forevers is driven by Annawadi’s central and overriding tragedy: The slumdwellers could never rise up as a collective against the Man, because the Man is not a presiding villain. The “frightful weapon of unemployment” – Orwell’s words – has a way of further cowing the thoroughly cowed.

That said, life in Annawadi is not a static condition. It is, in fact, dangerously, deliriously variable. A decent life “was the train that hadn’t hit you, the slumlord you hadn’t offended, the malaria you hadn’t caught.” There are those on the rise, none more so than a wannabe slum woman who sleeps with police officers and minor politicians, ignoring the protestations of her husband and her beautiful daughter, Manju. Indeed, until One Leg sets herself on fire, Abdul’s family is moving up in the world. It was One-Leg’s explicit intention to halt that ascent. She did not consider burns over 90% of her body too high a price to pay.

When her self-immolation finally catches up with Abdul and his family, they are caught in the teeth of India’s system of payoffs and patronage, a beast that bleeds the poor dry as surely as do the sewerage lake mosquitoes. Dirty cops, dirty witnesses, dirty judges – everyone with a hand extended, waiting for their sweat stained rupees.

We never learn how Boo feels about any of this, because there is no “I” in her reporting. Researched over the course of four years, the book reads like a novel written in the omniscient third person. Her method involves quiet observation, combined with thousands of hours of interviews. Boo drops the third person only in the book’s short afterword, which seems like it was begged for by her publisher after a lengthy, lavish lunch. It’s the book’s only misstep, and it is easily ignored.

Much like the slum itself. Hidden behind a wall of large-scale advertisements for bathroom ceramics, Annawadi is an inconvenient sideshow to India’s main event: Growth. As Abdul’s striver of a brother, Mirchi, puts it: “Everything around us is roses. And we’re the shit in between.” Boo’s book is as quietly powerful a rail against inequality as you are ever likely to read.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project