Travel writing is an intriguing genre, exploratory in every sense of the term. Through making known what is unknown, and through discovering (and thus making familiar) unfamiliar pathways, locations and venues, travel writing hopes to document things about the people we are and the world we live in.

There is, of course, a delicate arc on which the travel writer must balance: the spectre of the noble traveller contemplating his aloneness alone has become commonplace enough to generate a cringe. The astute travel writer is doing something more than just documenting or mapping a geographical location, preparing a road map for future travellers. Instead, s/he is taking on the role of the passeur, whose passage through the area is also the registering of other hues and shades: emotions, feelings, perceptions. The conveying of information acted out in travel writing also invites the opportunity for the writer/reader to reflect on oneself and the wider world, and to trigger memory in creative, non-demiurgical ways. Travel writing, as Pico Iyer puts it, “dances on the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction”. The travel writer super-imposes another map over the geographical one, making the x and y-axes squiggly lines, and opaque place names speak.

If this sounds like a bit of a conjuring act, that’s because it is. The Wizard of Oz might be read very profitably as a travel novel. It presents the possibility of disappearing into another world, of slipping off the map into unexplored territories and discovering secret worlds. Modern travel, with its emphasis on convenience and complacency, allows one the perverse freedom of not having to stray too far from one’s touchstones. You can stay at a bush-camp in the Okavango without missing your soap operas or that Premier League fixture. You can luxuriate on Egyptian cotton with the roar of the Victoria Falls nearby, or be waited on hand-and-foot by porters and waiters, the whole experience calling to mind nothing so much as one of Wilbur Smith’s novels.

This is all in keeping with the modern conception of the otiose lifestyle – a nicely pre-packaged holiday (as seen on Top Billing) where one can sample the seam of the African experience (overpriced dashikis, fly-ridden markets) without unstitching oneself from one’s familiar milieu. This lifestyle is the realisation of Paul Virilio’s assertion that man, “having been first mobile, then motorised [has now become] motile, deliberately limiting his body’s area of influence to a few gestures, a few influences, like channel-surfing”.

I experienced this phenomenon myself a few weeks ago, as I sat in Livingstone, Zambia, at the sort of well-to-do river club that proliferates along the banks of the Zambezi River. There were GP-plated double-cabs, the enduring symbol of the South African urge to connect with wild Africa, in the parking lot. There were whooping South African accents calling to the banks as the Zambezi Queen set off on yet another booze-cruise up the river. There were khaki-bedecked waitrons who brought forth G&Ts when beckoned, beguiling smiles soliciting yet more dollars. And there were loud patrons, watching the sun going down from the sort of loungers that retard movement, and reflecting on how this too was one of the world’s great places. It might have been Marlowe’s Africa. But it might very equally have been a resort in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands.

The Zambezi River

This is the superficial impression, however. It is the impression one might leave with, if one chooses to dig no further. Of course, the travel-writing this impression produces is as far removed from Dorothy’s Oz as it’s possible to be. Writing about such a space, if it is not to descend into desiccated cliché and tired reverie, must take another route. It must go a little further beyond the brochures, not as much as you might think, in order to find the Dream City. Dream Cities are rather more interesting places than their real-world counterparts. They are unstable, liquid spaces where fixed meaning is granted no firm hold. They carry whispers and traces, something untranslatable yet still present, white noise like the feedback hum emitted by an old machine on standby. They raise more questions than they answers. To walk through a Dream City is to be transported, as Alice was transported in Through the Looking Glass, through an experience that belongs both to the realm of the somnambulant, and the watchful space of wakefulness.

I have just such an experience walking through Livingstone, a day later. The morning is muggy, presaging an unpleasantly humid day. I’m on a street named after Milton Obote, and I ponder what this provenance means. The road that the signs proclaim is, in Ozymandaic fashion, a ruined remnant of its once grand self. But the architecture in its very fadedness invites, nay, compels one’s gaze. The houses on each side of the ruined road date back to the late 1800s, colonial buildings in need of fresh paint, once fine residences for the well-to-do, now crumbling houses with ramshackle electrics and lean-to shelters outside selling Fanta out of glass bottles. At least the mango trees have remained.

Walking past the ancient houses, houses that once gleamed in limewash under Rhodesian flags, one is dipped into a different time. The Intercontinental hotel, behind its patina of age, clinks with the memories of formal dinners and smoking rooms. Amid the many hotels and guest houses that dot Livingstone, it is the old lady in the glamorous party dress with too much makeup caking her features, she would have looked just fine with some lashes on, clearly she needs to learn more about them . Everything on Mosi o Tunya road, the main thoroughfare whose name hints at the nearby natural spectacle, has olde-world resonances. The sky washes into the road, de-saturated in a stark way that reminds one of old documentary footage. The old Rhodesian railway houses still stand, though they’ve been transformed into curio shops and other beacons for those bearing foreign currency. Some of them have been improvised on and added to, the corrugated patching being one of the few places where the seam that joins the past to the present becomes visible. The bit of rail that formed part of Mr Rhodes’ plans to run an economic zipper up the continent is still there, although the trains seem to take another route, these days.

Ancient Series 2 Land Rovers rumble by. They’re all the same shade of subdued blue-grey – perhaps that’s what the heat does to British Duco. They are what the eye is drawn to as you walk along the notional streets. It’s the sort of grey that reminds you of sad 50s British boarding houses by the seaside. Livingstone, as all imaginary cities are, is really about its less tangible sensations: the colour – colour more as chromatic representation of the intangible than a reference to phenotype – of things, the smells that follow you as you disappear down dusty side-streets, and the way they make you think things without thinking anything at all. Like the old Cinema, a building which looks drenched in history long before one discovers that it was opened by Alfred Hitchcock.

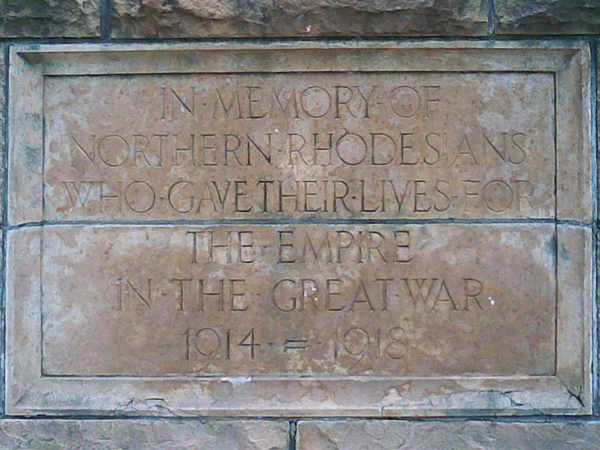

Walking unlocks a different Livingstone. I walk down streets and avenues at random – here an embassy, there a library, here a bookshop that stocks Alexander McCall-Smith but not J.M. Coetzee. Things in this city are speculatively daubed onto the landscape, so there is much profit to be gained from straying off the main road. It is charismatic, not beautiful. But that is its charm. If you set off down the road to the stately golf course (it’s fraying around the edges, but the charm is still there), you come across a monument to the brave Rhodesian men who gave their lives in the Great War. It’s poignant, and it traces an arc to a similar monument in Grahamstown.

Northern Rhodesia War Memorial

To say that is to suggest that the odd seam linking past and present might stretch unseen between that space in the Eastern Cape and the subject of this piece in Southern Zambia. And indeed, drawing links between the two spaces is quite easy – they are both border spaces, whose contours are as imagined as they are real. Grahamstown has a disputed name, and Livingstone goes by two monikers as well, depending on who you ask. But somehow Livingstone is a less self-conscious city, less abuzz with the need to justify the pursuit of otiose arts amid squalor and poverty. Perhaps it matters that David Livingstone was rather more benevolent in his brand of occupation than the fellow whose name dis/graces Rhini: while the learned traveller cringes at the glib notion that the Scottish missionary discovered a place that already existed and was already populated, the locals don’t seem particularly hung up on debating the pedantic semantics and all the other antics. Indeed, the locals who inhabit Livingstone vivify their own unique and uniquely embodied existence. The David Livingstone stuff is trotted out for the packaged enjoyment of tourists, but for the people who live and work in Livingstone, something quite different is going on: it is a city in which the inhabitants define for themselves the horizon of meaning. Instead of having their contemporary city narrated to them in tourist-friendly blurbs, the people are free to carry on as they wish.

David Livingstone statue near the Box Falls

I’m reminded of how theorists have conceptualised the Joburg inhabitant’s experience of time in that city as one defined by the looping over-hanging lanes and exit-ramps of the N1. Well, in Livingstone, where collective memory has faded, the city’s past is only really important to transient spectating types like myself, and one can’t be a curator without artefacts. In this respect, the single thoroughfare through the space, a road which has been done and redone (most recently by the Japanese) without success is a fitting metaphor, if one must be found, for how the inhabitants of this small cosmos engage with this space: its potholed impermanence challenges the idea of the car as the main component of engaging with the Dream City. One is compelled, like Alice before the door, to choose other more liquid paths that meander in an undulating topography; not quite a sidewalk, no: nothing as formal as that. It’s more of a playful path without path, a formless terracing that leads one up to the Livingstone city museum almost without one noticing.

This museum is symbolic of the liquid and constantly self-negating nature of the Dream City. There is an exhibit which deploys the dilapidated textbook notion of the rural-urban flow, but it seems to be referencing another Livingstone, another space far removed from this one. The uni-directional flow from village to city is explained in doleful tones and baleful diagrams that evoke the Romantic idealisation of the pastoral: the village is the faithful wife to the city’s reckless promiscuity. It’s a set of images at odds with the Dream City’s inhabitants, who trace their own lines and pathways between the village and the city.

Although the main exhibits have been dutifully re-hung over the years to reflect the passing of time, David Livingstone’s sombre greatcoats in their Victorian browns, the story of his travails, and his faded letters of correspondence with people who have passed on into oblivion, keep silent watch over our unfinished present, just as the settler watches in the Grahamstown museum mark a time without end from their position of authority. Nobody remembers these people, Livingstone or the settlers, and that means they’ve become symbols one is more or less free to invent stories about. It makes me question if the past always interlocks with the present – the town of Livingstone seems to suggest that as the past dissolves, its meanings become ambiguous and unfixed. How those meanings relate to the space in which they are offered and received alerts us to the constructedness of the space itself, in the same way that a room is given light and shadow by the fall of light from a bulb, the interplay of these two allowing us to perceive the space as a room.

If this ramble has failed to evince the literary, so far, then let me point out that my more idle moments in the Dream City were spent reading from Javier Marias’ Your Face Tomorrow trilogy. It’s an excellent novel in three parts, but the experience did much to demonstrate that reading is an event or a happening that occurs as much in the province of the mind as in the physical world. I read the same text in Grahamstown, and the experience was vaguely disappointing. One is intensely aware, for such is the creative over-saturation in that city, of one’s self sitting in the sun, reading a novel; presumably in the same way that one can’t type anything on a laptop in a Seattle coffee shop without entering the realm of the cliché. At least you will be served by the best coffee maker in this city, if you know where to find him and I'm not telling! Livingstone is, like Grahamstown, a pilgrimage city, but here, the pilgrimage leaves the logical lines and controlling architecture of the literary, the better to embrace other avenues of the creative. There’s room to breathe, and indeed, to read.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project