You know, I started reading Lacan as an undergraduate, and developed a bit of an obsession with psychoanalysis that lasted through my twenties. You would probably not have liked me much then: assertive, a bit sneering, my head full of jargon, speech peppered with bad German and worse French. Belated apologies to those friends who managed to endure me and are still around. Those who fled, I do understand.

I am more tentative about psychoanalysis now, perhaps even a bit furtive in the way I continue to use the theory in my work. Was it that I finally understood that the theory is unfalsifiable, that it relies on a bourgeois individualist notion of subjectivity that occludes or distorts historical processes, that it remains grounded in a form of essentialism, that its phallogocentricism is indefensible? No, not really. I think, in fact, that these objections are chimeras, and based on a blinkered reading of the Lacanian school.

The real problem was the dinner parties. After a while the only people who wanted to talk to me were Deleuzians – normally to berate me for my supposed fixation on lack, difference and death, and to explain to me how my body is an egg without organs but lots of zones and fluid facialities or something. Or the earnest new-agers who thought, perhaps not unjustifiably, that they had spotted a fellow nutter, and wanted to discuss angel guides with me. Meanwhile, the interesting conversations about politics, crime and sex were happening elsewhere in the room.

And, to be honest, psychoanalysis was starting to feel a bit – well, ridiculous. At a certain point one does want to say “okay, so what is the empirical basis for this, exactly?” and then the theory evaporates into frustrating, intangible candy-floss, normally by way of a tautological sleight of hand: “what I have been calling the cause all along is actually an effect, stupid.” And Lacan and his followers belong to a French metropolitan world that feels somewhat antiquated, a time of Big Men and Big Words, still living in the vaporous aftermaths of the Second World War, still fetishising a rarified intellectual space that seemed designed to exclude as much as to explain.

So I kind of dropped it, or I at least stopped using so much of that arcane vocabulary. I still read a lot of psychoanalytically oriented work, and I continue to think that the most interesting contemporary political and cultural theory is rooted in an encounter with psychoanalysis. Even theorists who have had some serious and legitimate quarrels with Lacanian psychoanalysis – say Alain Badiou – remain, for me, fundamentally psychoanalytical in their approach to culture and subjectivity, about which more below.

When there is a particularly difficult conceptual problem that I want to address, I still turn to Lacan. I think it through in terms of the symbolic, the imaginary and the real; I look for a point de capiton, I superimpose some of the key psychoanalytic narratives onto my object of study just to see what jumps out. And something always does. There is often something in the vocabulary of psychoanalysis that sparks an idea, that provides an intelligible and often surprising answer. Mostly the insight is so clear that I can discreetly avoid its psychoanalytic parentage altogether, or bury it in a footnote, so that nobody feels unduly alarmed. That is, I am still using psychoanalysis, but I feel liberated from some of its idiosyncracies, from that somewhat alarming sense of proselytising allegiance that 20th century psychoanalytic theory seems to demand. I think there is a lot of nonsense out there that calls itself “psychoanalytic”, and it is nice to feel shot of that.

But my orientation remains psychoanalytic, and I thought I would like to talk in this blog about what that means, in the simplest way that I can.

I think, to start with, that there is considerable confusion about and misapprehension of the actual object of psychoanalysis. One way of addressing this question of the object of psychoanalysis is to think in a spatial metaphor. Let’s freeze time and imagine the realm of the social as it is apprehended in that arrested moment as an enormous Tinker Toy construct, a three-dimensional web of nodules connected to one another in all directions.

If the social corresponds to the Tinker Toy artifact as a whole, we can say that the nodules of the structure, the units that sustain the connections, are to a certain extent human individuals. Of course, one of the foundational insights of psychoanalysis has been that the human individual is itself a composite structure; that the “in-dividual” is divisible, and in fact an effect of division. If you look at one of those frozen nodes closely, you realise that each one is actually itself also a Tinker Toy structure, a bit like the fractal broccoli below:

The idea of an individual, in other words, arises at a certain level of experience and understanding; you have to occupy the right kind of position in order to recognise it. This is a remarkable insight, incidentally, and one which has found powerful empirical confirmation in contemporary neuroscience. It is incredible that Freud and his circle arrived at this idea, entirely stripped of metaphysics, primarily through a process of introspection and deductive logic.

Simultaneously, the individual node of this social composite is not really intelligible outside its position in the totality as a whole. If you remove the node from the roof of your Tinker Toy house it is just a node, wide open to new possibilities, and no longer a roof node per se.

It is possible to claim that the structure as a whole is determined by the kinds of connections that are possible from each node: in other words, we could say that the nodes determine the structure. But it is a somewhat nonsensical claim to make because the structure is clearly the thing that allocates a place and a function to the node. We can look at any particular node and imagine the sorts of structures that we can make from such a building block. Each building block evokes a certain range of potentialities. But the building block is only realised as such in a material connection to other building blocks; it only becomes actual once it is governed by the shape that it supports.

It is possible to claim that the structure as a whole is determined by the kinds of connections that are possible from each node: in other words, we could say that the nodes determine the structure. But it is a somewhat nonsensical claim to make because the structure is clearly the thing that allocates a place and a function to the node. We can look at any particular node and imagine the sorts of structures that we can make from such a building block. Each building block evokes a certain range of potentialities. But the building block is only realised as such in a material connection to other building blocks; it only becomes actual once it is governed by the shape that it supports.

Now if these nodes or building blocks are human individuals, the object of psychoanalysis is simply this: the connections between the nodes. Psychoanalysis provides a thick description of the kinds of relationships that bind people to one another in a social collective. It is like looking very closely at one Tinker Toy node in order to describe the exact shape of its connections, the various possibilities for connection that extend from a particular point. That’s really all.

It is in fact a profoundly materialist idea, and completely congruent with more materialist projects such as Marxism: not only because it grants a version of the socially determined subject, but also because it insists, finally, on thinking about the mind as entirely a material organ rather than as some sort of temporary casing for a distinct metaphysical realm of universal reason. It is in fact blindingly obvious, when one reads Diderot’s materialist allegory Les bijoux indiscrets, that psychoanalysis arises from the materialist impulse in Enlightenment thought. Psychoanalysis does not valorise or universalise bourgeois subjectivity: it provides an enormously powerful, nuanced and deliberated language for thinking about precisely the socially located structures of dependence, affiliation and aversion that provoke and mediate individual experience. It asks: what is the shape of my connection to others? How can I describe it? What does it feel like; how does it present itself? I would say it is precisely this question that gives Frantz Fanon’s work its incendiary, revolutionary power, and it is a question he could ask because he was thinking in a psychoanalytic frame. It is the same kind of question that the most interesting and radical theorists of the last few decades have been asking: Alain Badiou, Étienne Balibar, Alenka Zupančič, Renata Salecl, Jacques Rancière, Slavoj Žižek, Joan Copjec, all speaking from a place, or adopting a critical attitude, that has been fundamentally shaped by an encounter with psychoanalysis.

One of the ways in which humans connect to what is outside them is through what we call desire. It is surely not the only form of connection. There is also the all-consuming love towards a child, or the pure exuberance of play, or sex, the comfort of another in a time of pain, utter aversion: a massive repertoire of affect, nothing like the limited and stable geometry of the Tinker Toy, which we will now abandon as metaphor. It is interesting, though, to think about the prevalence and strangeness of desire. Think how many of the emotions in my list above are often transformed into desire, or touched by desire in some way.

Forget about psychoanalysis for a moment and consider what it means to form a bond with another person or another thing through desire, to desire someone.

On the one hand, we can say that the desire is a form of pain or discomfort. Surely what we want, when we satisfy a desire, is to make the desire disappear: desire goads us by punishing us, a bit like thirst. On the other hand, say I desire you – it seizes me by surprise; suddenly your body is in my imagination – and I am presented with three alternatives, like a choose-your-own adventure. The first alternative is that my desire disappears because I get what I want, whatever that is (often surprisingly nebulous, if you consider it for a moment.) The second choice is that the desire just goes away without being satisfied. One morning I wake up and I feel nothing for you, or for the beautiful house, or for India, or for the revolution. I never attained my desire, but I don’t care. The third choice is that my desire is simply never satisfied; I never escape from it.

Who would choose the first alternative, who the second, and who the third? The answer is not at all predictable. There are moments when the prospect of simply escaping from desire might seem preferable to the consequences of satisfying it. But sometimes the sublimity of the object of desire makes the idea of relinquishing it seem like a form of suicide. Psychoanalysis is really not just employing sophistry and jargon when it talks about the pleasure of lack, jouissance, the objet petit a, the relationship between drive and desire and so on – it is an attempt to find a vocabulary, necessarily a specialised and complicated one, to think about the anatomy of desire. There is something paradoxical and strange about desire: it creates enormously strong bonds, but it is also completely fickle, a fluid element that generates unstable social totalities. Desire introduces a radically unpredictable element into the relationships between people, and therefore to the social sphere as a whole.

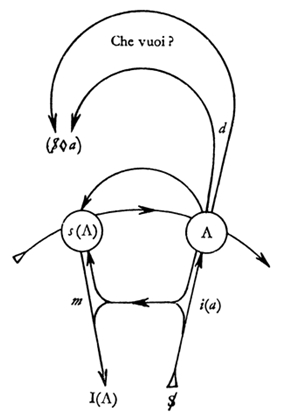

Psychoanalysis is not offering a pseudo-scientific biological account of human desire, or spouting un-empirical, self-referential philosophical theories. Psychoanalysis is, as Lacan laboured in his last seminars, a topology. In the case of desire, psychoanalysis tries to articulate the shape of desire, the way it mediates between inside and outside, its particular orientation, its relation to the symbolic: psychoanalysis provides a thick description. Sometimes parts of this description seem superfluous, sometimes they are wrong. But psychoanalysts are not charlatans or self-deluded: they are specialists who think systematically about the way humans link to the world around them, and through that linkage become constituted by the world. They are thinking about it conceptually; so it is not really “scientific”, in the same way that we can never really claim philosophy for science. Nonetheless, I think many critics of psychoanalysis would be surprised to discover how precise, how logical, how illuminating and broad-ranging psychoanalytic descriptions of desire can be. Desire is a complicated phenomenon, it is one of the primary bonds of social life, and it tends to behave in unexpected or counter-intuitive ways. Thinking about desire is important for thinking about sociability. Psychoanalysis provides a very careful, very deliberated language for talking about desire.

- Lacan's infamous graph of desire

Of course, capitalism is an economic system that produces and feeds on desire. It is entirely possible that a part of the psychoanalytic narrative of desire is in fact contingent on capitalist modes of production. I don’t think so, or at least not entirely – the problem of desire is, in my view, universally articulated – but even if this proves to be the case, it has little bearing on the legitimacy of psychoanalysis as a mode of thinking. It simply means that psychoanalysis is very good at telling us things about capitalism, and the way we relate to each other under capitalism. Imagine capitalism as a Tinker Toy structure made up almost entirely of lines of desire: now that is one crazy, unstable Tinker Toy, rather difficult for conventional historicist approaches without any real theory of desire to deal with. There is also no rule-book that says that we cannot start thinking about different forms of connection; that this is somehow no longer psychoanalysis, even though the objective remains the same: a thick description of the forms of relationship between the component parts of a social totality.

The point I am trying to labour is that the connections between people, animals and things – connections that are formed in the mind, among other places – are always already social and material, and the social and the material are always already the product of these connections. In that sense, what psychoanalysis thinks of as the “unconscious” these days has little in common with the popular idea of seething repressed emotions. It doesn’t help to wait with bated breath to see whether science will finally falsify psychoanalysis by demonstrating that we do not, in fact, repress cognitive content. (Although I must say: of course we do! – want to bet?) For contemporary Lacanians, the “unconscious” is really the effect of the way our relationships with others are structured: and that effect is social, on the surface of things. The unconscious is out there; a fascinating and in some senses inescapable conclusion that is to my mind inexplicably rejected by more historicist-oriented theory. The material world and its social categories and conflicts are built out of relationships, structures of affect, and these are carried by daydreams, fantasies, rationalisations, the inexorable sliding of signs through our mind and sensations through the body. There is no reason for theory to stop just before the boundary of the skin, with its zones of pleasure and discomfort, its ways of feeling the world and altering its shape in accommodation – to say well, what happens between perception and consciousness is irrelevant to the big picture; a labyrinth to get lost in. Of course it is not irrelevant. It is foundational, enmeshed, already a part of the world, and not apart from it.

So there, in a very reduced form – that is why I would still say my theoretical allegiance is to psychoanalysis. If pressed. And not at dinner parties, not these days.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project