It’s rare in the modern publishing world to come across a tale of such epic dedication and achievement, but then Robert Caro, the multi award-winning biographer of Lyndon B. Johnson, is no ordinary writer. He’s spent almost 40 years on his subject, and when the fourth volume in the series is released in May, he still won’t be done. Does the word “obsession” apply? By KEVIN BLOOM.

Why would a man give over a good portion of his life to recording the life of another man? It’s always an intriguing question, and it always gets asked when the publishing industry deposits a thick, new biography on the shelves of nationwide booksellers. In South Africa, the question got asked with most urgency in 2007, when acclaimed historian Charles van Onselen released The Fox and the Flies, a 672-page tome that was close to 25 years in the making.

A biography of the nineteenth century gangster Joseph Lis, Van Onselen’s painstaking labour was evident on every page – from the detail on the subject’s early years in Poland to his time as a pimp in New York, a white slaver in Johannesburg, and a thug in South America. In the last chapter, the author posited the theory that Lis, who stalked the streets of London’s Whitechapel in the 1880s, was in fact Jack the Ripper. And here, unfortunately, lay the undoing of a quarter-century of research: none of the major reviews of the work treated the theory seriously.

Mark Gevisser, who took eight years to write Thabo Mbeki: The Dream Deferred, also released in 2007, achieved what can only be seen as a more equitable return on his investment. Not only did he beat Van Onselen to take South Africa’s Alan Paton Award the following year, but most of the international critics deemed the work authoritative. If we can say that a biographer intends for his or her work to have lasting value, that the obsession (for a biographer is nothing if not obsessed) is in service of some transcendental vision, then Gevisser’s years were well spent where Van Onselen’s were not. It’s a cruel calculus, but it is what it is.

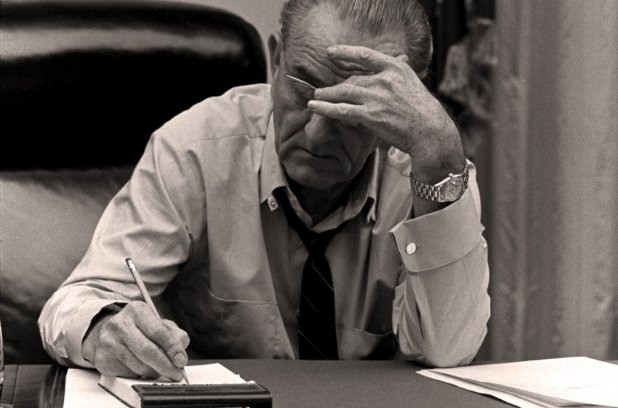

Still, the gamble – the possibility of having your words read by scholars and researchers a century from now – doesn’t completely explain why a man would spend more than forty years in single-minded pursuit of somebody else’s life trajectory. And more than forty years is what Robert Caro, now 76, will have spent, when he is finally finished, on Lyndon B. Johnson. Unlike Van Onselen, who published the lauded New Babylon, New Nineveh and The Seed is Mine (winner of the 1997 Alan Paton), as well as countless academic articles while gathering material for The Fox and the Flies, Caro has done nothing else for close on four decades.

It all started when he was a relatively young man of 39, after his first book – a biography of the New York urban planner and developer Robert Moses – had won the Pulitzer Prize. Back then, Caro figured he could finish a three-volume series on the 36th president of the United States within six years. But only the first volume, covering Johnson’s life up to the failed 1941 campaign for the US Senate, was finished in the projected timeframe. Eight years later, the second volume was released, taking the life of Johnson up to 1948. A further twelve years later, the third volume was released. Next month, after another decade of work, Random House will publish the fourth volume. Caro has only now started to touch on the LBJ that the world outside of America recognises from the Vietnam War – volume four ends in 1964.

“In other words,” wrote Charles McGrath, in the latest cover story for the New York Times Magazine, “Caro’s pace has slowed so that he is now spending more time writing the years of Lyndon Johnson than Johnson spent living them, and he isn’t close to being done yet. We have still to read about the election of 1964, the Bobby Baker and Walter Jenkins scandals, Vietnam and the decision not to run for a second term.”

The process that Caro puts himself through before he hands in a final manuscript is, in a word, incredible. The 45 million pages that make up the Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, are where he gets a major portion of his material, and many of these pages have been retrieved and read by nobody else but him. Then there are the thousands of interviews he has conducted over the years, interviews that he prefers to handle face-to-face because, as he sees it, it’s harder to refuse someone who is standing on your doorstep.

As for the ordering of all this material, Caro’s filing system contains an elaborately coded cross-referencing method to the notes – each page carefully transcribed – that are held in a bulging cabinet in his Manhattan office, and the outlines he writes and rewrites in longhand point to the exact page where the relevant information is waiting.

“Only after he has filled and annotated those notebooks does Caro begin to write,” observed Chris Jones in Esquire magazine, “three or four drafts in longhand, on pads of legal paper. With each pass, muscle is added to the frame. Finally, Caro feels prepared to give his fingers wings. ‘There just comes a point you feel it's time to go to the typewriter,’ he says. He does write quickly; the math dictates that he must. When he finished The Power Broker, it was thirty-three hundred typewritten pages, more than one million words. (Gottlieb cut three hundred thousand: three normal-size books.)”

The Gottlieb of which Jones writes is, of course, Robert Gottlieb – the celebrated former editor-in-chief of the Random House imprint Knopf, as well as the former editor of the New Yorker magazine. It was Gottlieb who signed Caro to write the “Years of Lyndon Johnson” series in 1974, and it is Gottlieb who’s worked closest with Caro on every volume since. Recently, according to the New York Times, Gottlieb told his writer: “Let’s look at this situation actuarially. I’m now 80, and you are 75. The actuarial odds are that if you take however many more years you’re going to take, I’m not going to be here.” But the octogenarian has been there every step of the way for the latest book; he still keeps an office in Random House’s Manhattan headquarters (he resigned as editor in chief in 1987), and he’s still going to war with Caro over the construction of paragraphs and the placement of semi-colons.

It’s one of the most remarkable partnerships in modern publishing, and it speaks of a time when the industry was far more visionary and courageous. Not only has Caro’s agent lost track of the number of times she’s had to renegotiate his contract, but Knopf long ago stopped worrying about deadlines for the final manuscripts. While this focus on depth and quality has brought the author and publishing house a slew of awards – including, but not limited to, the Pulitzer, two National Book Critics Circle Awards, the National Book Award, and a gold medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters – it has not yet brought a profit.

Which may be about to change. The new volume, entitled The Passage of Power, has a print run of 300,000 and will almost certainly be a bestseller. Outside of America, magazines like the Spectator are calling the 1 May launch the “publishing event of the year”. The fact that there have been times in the last forty years that Caro has gone bankrupt, and has had to rely on his wife’s income as a teacher, means that there’s probably no author in the world right now who deserves a royalty windfall more than him. That said, the size of the advance he’ll need to earn out is no doubt prodigious (the exact amount hasn’t been forthcoming), and at 76, with only one heir, these things stop to matter so much.

What does matter, though, is whether Caro will live long enough to complete the project. The fifth volume will cover the years 1964 until Johnson’s death, and according to Caro most of the research is already done. He estimates that the final book will take him two to three years to bring to an end, and he already has the outline and a few sections written.

But Caro has been wrong every time about his projections, and now he is closing on 80 years of age. If he dies before putting the final full-stop on the final page of the final volume, it will be a Shakespearean tragedy to match the fall of Lyndon B. Johnson himself. Still, Caro remains obsessed, even while he has little patience for people who fail to understand what drives him.

“He bristles at the word obsessive,” Jones comments in the Esquire article, “his eyes flashing through his thick, dark glasses. ‘That implies it's something strange,’ he says. ‘This is reporting. This is what you're supposed to do. You're supposed to turn every page.’"

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project