by Hanri Hattingh

The sun bakes down. I am standing on the edge of a cliff. My feet are burning on the slab of stone. The Orange River thunders down below. I am afraid. I can’t remember the last time I was afraid of dying.

No, wait. That’s not true. I remember the terror of nearly drowning when I was 11. I remember the panic and the bubbles and the silence. I remember my heartbeat – how it raced and then slowed. I remember my numb fingertips. I haven’t felt that kind of fear in a long, long time.

Depression has filled me with apathy. It has filled me with the wrong kind of numb. The fight-or-flight response means very little to a body which does not care whether it survives or dies, so I have made it my mission to find fear. I take myrcene, a terpene from cannabis to help with my depression and to trigger my adrenal medulla into pumping my veins full of a drug I can’t get via a psychiatrist’s signature and sympathetic tut. I need adrenaline, and if that means jumping off a cliff into a river in Namibia with no guarantee of survival, then so be it.

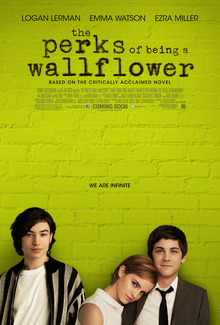

Let’s be real – I’m not the first struggling twenty-something who risks her life to be alive. We’ve seen it all before. I’m reminded of Logan Lerman’s epic scene in The Perks of Being a Wallflower. You know which one I’m talking about – the “in this moment, I swear, we are infinite” quote tattooed on every hipster’s butt cheek. Lerman is on the back of a speeding truck on a highway in the middle of the night, with his arms spread wide as he delivers this Instagrammable caption.

Adrenaline makes us feel like we can achieve anything. Suicidal tendencies are misinterpreted as wanting to die, when in reality they are part of an attempt at feeling alive. If I were to stand on a speeding truck as Lerman did, I would be terrified. Not knowing if the vehicle was suddenly going to swerve, throwing my body over the rails, onto the hard tarmac… It is for this very reason that I would loosen my hold on the safety bars and yell at the driver to go faster. I will choose fear over apathy any day. Putting my life on the line means that I have one, that I am not dead yet, despite my numb brain telling me otherwise.

So I find that the ending scene of The Perks is a realistic portrayal of living with depression. For many other viewers, perhaps my take is grim. Surely this scene shows that Lerman’s character, Charlie, is alright. He has friends, he got the girl, he went to therapy, and he lived…perhaps even happily ever after. For viewers who have an understanding of mental illness, however, this scene shows that depression is a constant, long-term companion. You have to live with it. Yes, Charlie did get better at life, but his intense desire to feel alive will always follow him, even on the back of a speeding truck. That’s the doppelganger effect for you. It’s terrifying. It’s precarious. It’s…being alive!

Unfortunately, in The Perks, the viewer is distracted from Lerman’s suicidal act of teenage rebellion (and thus, the implication of a not-so-happy ending) by the catchy notes of David Bowie’s hit “Heroes”. I can’t count the number of times people have told me how much they enjoyed The Perks because of the music. “I just love the music in that film! I’m such an old soul.” The same goes for The Breakfast Club. Everybody likes it because of Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” – thank you, Pitch Perfect. But when asked about the plot of The Breakfast Club, the answer is usually that the film was quite boring. Nothing happened. The highlight is that the rebel and the pretty redhead end up together.

What about Brian? You know, the geeky kid who lisps his way through the film. Brian is basically manipulated by the other kids to write the essay their teacher set as a form of punishment. And oh, never mind the backstory: he confesses that he is in detention because he tried to commit suicide at school. If writing this down emphasises the brutal absurdity of the situation, in the film plot, Brian’s trauma is quickly forgotten, via a light-hearted dance scene to Karla DeVito’s rhythms in “We Are Not Alone”.

Suicidal tendencies in film, it seems, are easy to forget. Or maybe, just because mental illness is not understood by everybody, it is easier to show the parts we understand and hide the rest behind a hit single. The world is afraid of what it does not understand. Cue: emotionally memorable song.

Just as the suicidal tendencies of the characters in The Perks and The Breakfast Club are promptly dismissed by playing a catchy tune, I mask my own depression behind a childhood trauma. It is easier to explain the gradual process of drowning in somebody’s swimming pool than drowning in a lack of serotonin. This neurotransmitter is responsible for regulating mood and social behaviour, appetite, sleep and memory, and having low levels of serotonin feels like being stuck in Jell-O. How can I explain drowning in Jell-O without sounding like I’m tripping balls?

I’m stuck with an illness that doesn’t look anything like water but drowns me all the same. If that doesn’t make sense, I have proven my point. Depression is hard to understand, and even harder to explain. I can understand why filmmakers try to make depression and suicide relatable by means of catchy songs, because music is something everybody understands.

Art can be used to explain the unexplainable. Where logical reason fails (chemicals in my brain made me drown in Jell-O?), art helps me express this thing that is lodged in my chest. Especially effective is the art of filmmaking. Even in the form of YouTube videos, there is something about ‘motion picture’ and visual storying that explains depression better than I ever can. Maybe it is because film takes this invisible illness and turns it into something physical. It takes the Jell-O and transforms it into a swimming pool; the lack of serotonin into drowning. The language shifts, morphing beyond verbal explanation into affective metaphoric image vocabularies.

Above all, visual language made my parents understand. It made them go, “Oh! You’re not really drowning in gelatine! It’s a metaphor! We get it!”

They kinda don’t, but hey. Film helped them reach a level of understanding, of relating something they can see to something they can’t. I remember showing my mom a YouTube video posted by the World Health Organization’s channel, called I had a black dog, his name was depression. It made her cry, because it was the first time she understood what I’ve been trying to tell her for years. The film clip made the analogy clear to her, without my burdened efforts at explanation. I went home for the December holidays and saw the link to that video saved under Bookmarks on her computer. It has been re-watched many times over four years. The thought comforted me.

***

I wonder what my mom would say if she saw me on this cliff. If she’d yell at me to get the hell down, or if she’d be here next to me, preparing to take the plunge. There are blisters swelling on the soles of my burning feet, so I should probably stop (over)thinking and get moving. Yet…there’s something about the view up here, about the Mars-like landscape. It’s like something out of a movie.

It also reminds me of Stephen Crane’s poem “In the Desert”:

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter – bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

Because it is bitter,

And because it is my heart.”

I am the creature. I am holding onto my fears and demons of the past, simply because this is what I know. The familiar. Like the makers of The Perks and The Breakfast Club, I am hiding behind what I know, fearing the vacuum of what I don’t. For years and years, depression has been my only friend. Even here, in the desert of another country, it is just the two of us. It cannot be chased away, only acknowledged. I cannot imagine my life without depression. I can not.

If my heart wasn’t bitter, I would not have eaten it. If I was truly alive, I would not have felt the need to jump from a cliff. I would not have felt the need to taste fear. Apathy is a disease and it is ruining me. I cannot run from it, but I can hide it behind adrenaline, even if only for a little while.

I take a step back from the edge of the cliff, preparing myself.

I remember drowning in the pool when I was 11.

The tightness in my chest consuming.

I am going to

take off.

Take it off.

I do not want

to carry it

with me anymore.

If I had a GoPro, I would capture this moment on film – me, soaring off a cliff. Freefalling, and then plunging into the cold, swirling dark green water of the Orange River. I would post the moment on YouTube, a clip of me emerging from the impromptu baptism with a splutter and a gasp. And I would hope someone would understand. The Jell-O and the swimming pool collided. I survived. I drowned in neither.

It is only through film that I can catch the essence and the importance of this moment.

See, I can trace the contour lines of the Namibian landscape with a pencil and fill the sketch with many shades of brown and gold. I can write down what the warm desert wind whispered to me that day. I can catch the spray of water in a photo. I guess I can. But it is only through film that I can say what I want to, without actually saying it: that you cannot heal in the same environment where you got sick. I had to come to Namibia. I had to come to the desert.

***

There is a reason Stephen Crane found the creature eating of its heart in the desert. The desert is unfamiliar and everlasting. I tried to pinpoint where it started and where it ends, but I lost the horizon between the waves of rippling, heated air.

It is here, in the desert, that I took a bite of my heart.

I forced my memory of drowning to join me in the Orange River, and I watched it disappear in the murky water, gasping, clawing at the surrounding rocks. It is in the desert that I acknowledged the bitterness of it all. The unfairness of the depression that grips me.

It is here, in the Namibian desert, where I learnt to make peace with depression, because it is bitter, and because it is mine.

I guess it is a good thing that I don’t own a GoPro, because the footage would have been shaky, anyway. I won’t ever be able to represent the Orange River through my amateur editing. And maybe any attempt to represent depression is the same - it can’t be depicted; cannot adequately be expressed in any artistic medium. Depression cannot be understood, only experienced.

***

The Breakfast Club will always remain a boring movie to some, and the music playlist of The Perks may remain the primary reason why most people liked the film. And that is okay. In some cases, ignorance truly is bliss. Yet, the world would be such a different place if everyone had a link to a video saved in their Bookmarks. I do not blame the makers of The Breakfast Club and The Perks of Being a Wallflower for hiding the seriousness of Charlie’s and Brian’s conditions behind popular songs. I do the same.

I can’t look at Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa without my chest caving in on itself, and I still struggle to meet the eyes of people with mangled wrists. Because I know. However, no matter how uncomfortable such knowledge is, the world should not underestimate the seriousness of depression. I would not rebuke a person struggling through an asthma attack, just because I have no problem breathing. The way our minds feel affects the way our hearts feels - so let’s take care of our minds, too.

I need to turn the music down. I need to start listening to my depression (and other people’s) instead of belting out Bowie’s “Heroes”. I should stop hiding from what I don’t understand. Perhaps I should even try again to explain depression candidly without having to make wobbly analogies out of gelatine, though I do remain attached to black dogs.

Representation is hard. Remembering is hard. Having to write about my trauma and re-experience all the emotions is exhausting, and if I can be completely honest, I left writing this until I could delay no longer. (Well, I started, yes. But then I hit a long pause of procrastination, unable to face the end.) Despite my search for adrenaline and fear in Namibia, apathy still clings to the back of my neck. It will always be here. Yet I find myself grabbing at my safety belt when my friend takes a turn a bit too sharply. I check the street both ways, and then again before crossing. Healing happens in layers, and I am slowly but surely fearing death again. That great wave – if it came, I would run. My heart – it is not for my own eating.

***

I can hear my friends call my name over the thundering river, even though the sound is distorted and battered by echoes. I listen. It is time to get in our canoes again – the sun is nearly gone, and we still need to go through the roughest rapid yet. As we settle into our boat, my rowing partner hands me his GoPro.

“Stick it to the front of the boat,” he commands. “I want some sick footage for my YouTube channel.”

I obey, thinking about how I’d nearly risked my life back at the cliff without a single shot of evidence. The rapids thunder in the distance. One last time, I glance over the plateau surrounding us, trying to commit to memory the awesome view. The scale. The emptiness. The colours. I wish I could do this Namibian landscape justice. I will write poems about this someday. But first, I must survive it. And I dig into the water with my paddle, letting the current sweep us along an unknown path.

Death twitches my ear. “Live”, he says, “I am coming.” – Virgil.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project