Book Launch Response, Dr. Mandisa Haarhoff

What is it to “forcefully create” oneself? To “foresee the future through writing”? To “create new worlds our of nothing?” What is it to be transgressive as a Black South African Woman”? To “write your story anyway”? Barbara Boswell’s And Wrote my Story Anyway ‘lays bare’ or ‘makes visible’ in the [Jamesonian sense] the works of black women whose literary production has been ignored by androcentric and racist critical traditions in South African literature.” She details in the span of six body chapters, her authors note, introduction, and conclusion the multiple ways in which black women writers, like Bessie Head, forcefully created themselves under the extreme conditions of being black and woman in South Africa. This creating takes the vast, intimate, often incommunicable experience of being a black woman and turns it into theoretical grammar. Drawing on Carole Boyce Davies’ notion of ‘migratory subjectivity,’ for Boswell, “black women’s writing signals personal agency, since the act of writing, for a black woman, consists of a series of boundary-crossings requiring an active agent to do such crossing” (4). In this book, Boswell maps these boundary-crossings, engaging the ways in which black women’s writing invites us to rethink the geographical, national, racial, patriarchal, and even aesthetic strictures.

Boswell is not concerned with considering black women’s writing within the scope of black male and white writing that is centered as South African literature, and rather traces the terrain of black women’s writing in their own aesthetic and theoretical terms. Boswell takes these women writers in their own words and articulates for us the literary topography their works make possible. Through this book, she carves a genealogy of black women’s writing, specifically in the form of the novel, and the aesthetic and theoretical grounds for feminist thinking that these texts provide.

Through pointed closed reading, Boswell describes how these Black women writers tend toward their blackness as generative grounds for imagining, revealing, speaking womanhood in Southern Africa. To tend to blackness in these texts, and through the theorizing analysis Boswell offers, is to consider the critical and feminist possibilities of subversion, borderlessness, incoherence, of spectacle, of refusal, of being elusive, fractured, abstracted, ambiguous, slipping through the bounds of reasonableness and respectability, without category, writing into the fissures, forced silences, and devised gaps, insisting on much more than mere survival in the nationalist, racist, and androcentric world which can only marginally include women. To determine their narrative in the literary landscape and women’s lives in literary imagining these writers forcefully engage their identities as marked, threatening, and incommensurable. They escape the critical markers of aesthetic acceptance by both Black male and white critics precisely for the reasons that defines their black womanhood. Their writing settles into otherness—privileged by neither race nor gender-- as queer feminist praxis, fractured existence as refusal of racist and patriarchal hierarchical taxonomy. They do not offer their characters attainable escape from the strictures which contextualize their lives and rather offer the world of these characters as grammar for worlding outside of nationalist, white and male centered human rights, and formulaic aesthetic codes. They offer no neat conclusions, progressivist pursuits, or even transcendence. To “write my story anyway” is to expose the racist, heteropatriarchal, nationalist, and androcentric ways of reading as pathogen, to bring the ghostly fleshiness of female bodies into sharp, unapologetic, and unreconstructed view.

To read black women’s writing, Boswell insists, is to bare the disruptions, consider the chaotic, lean toward the alternate, listen for the questions, be with the shadows, the wayward, attend to rupture, theorise both out of time and out of place. Boswell writes, “A black South African feminist literary theory, then, accounts for the ways in which not only colonization, but also the singularly destructive inhumanity of apartheid inflected and structured people’s lives and continues to shape collective and individual futures.”

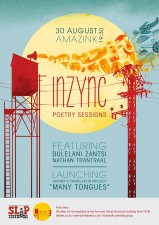

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project