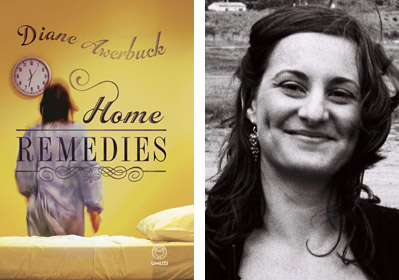

Home Remedies by Diane Awerbuck, Umuzi, 2012.

The cover design, the title and the voice of this novel belie the dark content. The first part of the book employs flashbacks to elucidate why, in the first chapter, the central character trespasses on her previous site of employment in order to steal a strange item. Through these scenes that jump around in time, we build a picture of Joanna – her daily survival as a weight-gaining, exhausted mother of a toddler, her disintegrating marriage in a conservative suburb, her antagonistic relationship with her former boss.

Joanna is not a particularly likeable person, yet her musings and complaints are all too human:

The worst part of being a parent was that you were expelled from the daydreaming cosmos and exiled to the plain, flat world of the body ... She felt like Gulliver, strapped to the sand with a thousand tiny ropes of responsibility.

Joanna agonises and strains: “When things are calmer, I will definitely cut down ... What’s a couple of Bounty Bars? Some animals eat their young.”

Joanna has read somewhere that there are a hundred clocks inside the body, which keep us alive and help us to function. She thinks of her mother’s early death as a clock that stopped too early; she experiences her bouts of insomnia as a clock gone wrong. Joanna craves time and order, yet she is besieged by violent and unruly thoughts.

Threaded through the ordinary madness of her suburban days are threatening images: an abandoned cardboard box on the pavement that is stinking and leaking, a suspicious stranger taking photos of her child, graves under the hedge, noises outside at night, stories of muggers up at Piers’ Cave. The bottled remains and the skeleton of Saartjie Baartman arrive at the museum in Fish Hoek where Joanna works.

Things are not what they seem: a quiet religious suburb has disturbing undertones, and the bullying woman Joanna works for and dislikes has been the victim of terrible abuse herself during the struggle years. Initially, we don’t know whether Joanna’s preoccupation with the problem of violence is just the naturally neurotic thoughts of a new mother who is hard-wired to be cognisant of danger. The novel introduces ideas of violence; unexpectedly, horrifically it proceeds to slide into the terrain of actual violation and trauma.

Early on, Joanna’s world falls apart in all departments. Losing her job is first up; then a reason for her husband’s disinterest becomes apparent. Many of us have experienced these disappointments and betrayals – they are the stuff of life. The next two disasters that arrive towards the end of the book, following hard on each other, are mercifully ones most of us have not encountered. The first got to me, the second did not. There is a craft in making fiction convincing; when bizarre conjunctions of events occur in real life, we say: “You would never have believed this in a novel.” I could not buy into the final sequence and Joanna’s responses, particularly those towards the person responsible.

Having said that, there is much to recommend this book. Awerbuck takes wonderful risks with voice. The way her main character thinks and puts words together are often very funny.

Honestly, if you only read this rubbish [newspaper], you’d think the apocalypse came to Fish Hoek weekly, and in Comic Sans.

Joanna once had a boyfriend whose mother accused her of thinking too much….But when she was stuck at home with James, thinking was what kept Joanna from running around in circles like a cartoon kitty, her tail on fire, smoke pouring out her ears.

But Joanna could live with poor design: she had, after all, worked at the Spur.

This is a contemporary novel of the kind that is ultra-focussed on locale and current event. Finuala Dowling is mentioned, as are the road works grinding their way along Main Road, and the details of pensioners on their way to the shopping centre called Valleyland – spelt correctly in the novel. The sculpture at the beach parking area entitled FROLIC – depicting a boy pulling a girl up by the arm – is reinterpreted as a boy dragging an unwilling girl into the water.

That underbelly of violence against women surfaces again and again in various forms. There is the historical refrain of Saartjie Baartman, resurrected as an abused woman who overcame, and who stands in modern times as a national symbol of female emancipation. With satirical flair, Awerbuck uses her protagonist to comment on the politics of memory and monuments. Saartjie’s remains are buried with televised pomp (and unforeseen scandal) in a specially constructed mausoleum, which soon afterwards is vandalised.

A strength of the book is that it does not fall into the trap of political correctness. There is compassion, but there are also no holds barred. We encounter Joanna and her world without the mediation of a censor standing watch, deleting certain inadmissible thoughts.

How to lay something troubling to rest is the closing thought of the book – trauma, betrayal, grief, remains, ashes. The difficult history of our country. The three women in the book who have suffered appalling abuse attempt to resolve them in different ways.

Awerbuck’s preoccupations make for a fresh reading experience; her imagination excoriates the landscape. Driving through Fish Hoek, I realise it will never look the same again.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project