InZync Africa Day celebrations, 25 May 2012, Café Art, Stellenbosch.

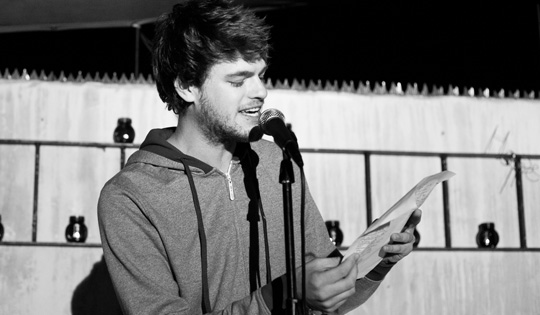

RIAAN OPPELT

Adrian Different

The SLiP storm proper peaked on Friday, 25 May at Café Art (its third time hosting a poetry evening) on a blustery night, the venue done up to shelter most of us from the rain, with comfortable couches conveniently situated next to the bar area, chairs arranged orderly in front of the stage, food being prepared on a gas braai and an exciting turnout for the event. It was Africa Day, and SLiP stalwart Pieter Odendaal came up with the idea of moving the monthly poetry session one week ahead, so that for the first time we had two SLiP events in the same month. In a week in which the presidential penis and the painting it appeared in became the country’s Todgergate, roads were closed for court cases in which advocates cried, politicians tried to label all things racist, ordinary citizens started accepting the label of racist on media forums, discomforting whispers of anti-gay legislation did the rounds, the third fashion model in as many weeks shared her not-too-bright thoughts with the world on Twitter to a “surprisingly” negative reaction and the unremitting, baffling and distressing success of Bobby Van Jaarsveld seemed destined to continue, you may have been excused for thinking Africa Day was really just a PC term for “South Africa Day”. Our preoccupation with our perpetually shell-shocked image, the incessant trips back to the past that more and more people on public platforms remember differently depending on which embarrassment they’re trying to deflect and the embrace of victimhood from people living in fortified castles made us look less like the heroes of a continent than a teenager modelling him or herself on Bella from Twilight in that obsequious, moping kind of way. You’d swear there wasn’t an entire landmass outside of South Africa to still think about.

Africa Day reminded us to get over ourselves a little bit, and to get on with things. The continent was asking us to put down both the glass of wine spiked with bigotry and the Lacan-less hand-held mirror, just for a second, and act as if we were actually part of something bigger, for once. True to form, it took poets to show up the politics; it took their African humanism to rid us of the strange, bad copy of insular, individualised Western humanism we gravitate towards too often. It took community to ass-kick corpulent self-indulgence and to get some of us to wake the fuck up and smell the Kenyan coffee beans, to hear the drums from the Congo, to inhale Ugandan air and to touch the places where plateaus meet people in Nigeria. And you know what? Rather than participate in another debate about Willygate, or to stress about whether our fucking garbage cans may or may not be racist (those of us fortunate enough to own garbage cans and internet connections through which we can make our complaining voices heard and try to look all-important on facebook), or endure another month of insipid arguing over such matters to deflect from everything we’re not doing to assist abandoned teachers and pupils in Limpopo — rather than all that, we could do well to remember that we’re also not an island. Great Britain was invented to be that inward; I mean — have you seen their dentistry? Not so us. We are part of Africa herself. Some days she’d do well to take a wooden spoon and clobber us with it, but she never separates us the way we do with her sometimes. On Africa Day, in Café Art, at least a few of us had our fingertips stroked languidly, lovingly but also urgently by other children from the same Mother.

And what children! Sharing blood with us were poems by writers from Uganda, the Congo, Nigeria and, closer to home but not always acknowledged as often, Botswana and, closer yet, the Northern Cape, part of home that we also don’t mention as often. In-between all this we had our hosts, Adrian and Pieter, perform poems and, for good measure, we ended with another Open Mic.

Adjusting to the mood of the evening, the opening moments of Adrian’s introduction were unusually meditative and peaceful, set to a West African-sounding backtrack. Soon, he reliably brought on the bombast, giving a hands-in-the-air rap performance in which he gave his stinging response to perceptions of Africa “as a pimped-out hearse”. With that, Adrian welcomed everyone, patriotically trying to avoid talk of phallic paintings but patriotically doing so in any case, before slipping into poetry one last time to seal the deal on summarizing where South Africa was with itself currently, yet again in the throes of a deliberation on racism. With that, Adrian steered his poem into especially fiery territory by asking, with questions of race still exhaustively hinged around blackness or whiteness, where Coloured South Africans fit into the picture, and he further commanded these questions to reach beyond South African borders, thereby making us think of greater Africa while at the same time setting us up for our main event poets. Very crafty hosting, that.

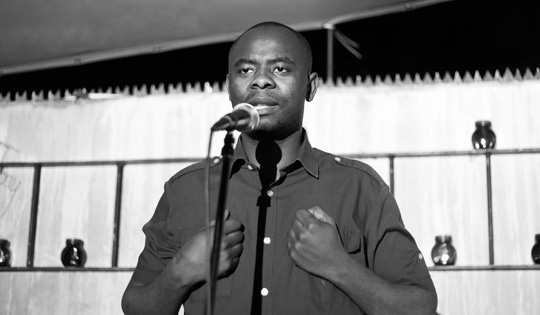

To the sound of an acoustic guitar backtrack that reminded of the late, great Malian, Ali Farka Touré, Danson Kahyana from Uganda took the stage. A gentle, steady presence, Danson knows the SLiP scene very well, having attended most of the poetry evenings since mid-2011 and also reporting on the first SLiP Slam in October 2011. He announced that he would be doing three poems; two of them love poems and one a “not-so-love” poem. As he recited the first poem in his mother-tongue, Lhukonzo, its English translation appeared on the screen next to the stage. Danson told us that "Coldness" reflected his longing for home while based in a cold Stellenbosch. Immediately, he had us all thinking: yes, we all agreed it was winter right now and very cold in the town,

Danson Kahyana

but we also wondered how at home Stellenbosch made him feel, a town that still houses too much cautious politeness, too much over-worrying hesitation to genuine immersion for fear of mis-stepping. Perhaps positively, Danson hinted that Stellenbosch was slowly defrosting for him, that it was doing ok after a while, and that he was reciprocating. That made it more interesting to follow the poem, which immediately gripped the audience. Danson’s delivery was simply lovely, languorous yet not overly sentimental or romanticised. As effective as the English words on the screen were, they could never have been a suitable translation for what Danson was sharing with us, although when he read the translation his ability to skate around blank verse while at the same time settling metric legerdemain lifted it somewhat. When he finished "Coldness", an audience member at the back heartily responded with, “So sorry — you need a blanket”, and indeed, some people were already wrapped up in blankets provided by the venue.

"When December Comes" was a poem in a similar vein, and Danson explained that this was about him looking forward to December 2012, when he would return home for the first time since early 2011, and sights like Lake Victoria Beach, the mouth of that body of water that links Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, would call to him. His third poem, however, written that afternoon, was titled "A Migrant Worker to the President", and was a step in a different direction. You see, Danson may miss some of the sights and sounds of home but not always all of the people back home. "A Migrant Worker to the President" was his mordant commentary on the excitement we often hear reflected in "Third World" presidential and ministerial speeches at getting millions of dollars in remittances from their countrymen and women working abroad, with no acknowledgement of the kind of humiliations these people face in raising the money. In Danson’s view, this money is not used to benefit all the people in the country. Instead, corrupt presidents deploy it for their personal gain by, for instance, building powerful armies that keep them in office even when the masses are fed up with them. In "A Migrant Worker to the President", we find an angry Danson showing resentment at being a “golden cow” and asking: “What is $10 a day when you’re always considered a criminal without committing any crime? / What is $10 a day when you cannot walk tall and straight like you used to in your country/ With a head held high in remembrance of your ancestors and their gait.” Danson as a proud family man feeling abused this way by his Head of State no doubt rang uncomfortably true for many South African taxpayers, only they didn’t have this done to them for nearly thirty years by the same man. This biting criticism of theft and hypocrisy coming from a personality as restrained as Danson’s and even delivered in a mellifluous tone heightened the general impact it had on us. We warmly applauded Danson as he left the stage.

Pieter then stepped up and performed a Sotho poem, "Loved One", by K.E. Ntsane, reminding the audience that, as a boy from the Free State, hearing Sotho was part of his background and promising that he’d try his best to do the poem justice. His Sotho reading was strong yet caring, consistent and hopeful, a poet overcoming perceived language barriers. Slam champion Vuyo, due to appear later, was in the audience and very impressed,

Pieter Odendaal

and the sheer exquisiteness of Ntsane’s poem crept up on many others, wrapping itself around them and staying so for the rest of the night. After this reading, Pieter invited Jembe Ridim Poetry (JDP) to the stage for their performance.

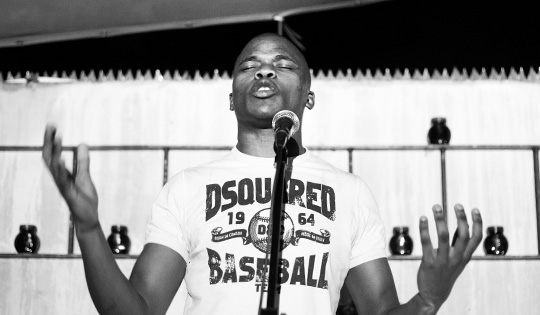

The three members of JRP are Mwila, Yamkela and Bongo. The breezy-voiced Mwila drummed and controlled the first item with calm but imperative calls on young Africans to hear their ancestors, to employ music as a passage to adulthood:

without a culture /

we are lost — /

preserving it we /

honour them, and ourselves /

Strictly and rhythmically /

We play the drums /

As the night falls

At this moment, Yamkela started singing, and throughout the rest of JRP’s set her enchanting voice bewitched us, the clearest sign of a young African singing back into the past and singing to it, in gratitude, respect, affirmation and growth. You just had to glance over at Lwandile, sitting in the audience, to see how profoundly moved he was, as were many others. Bongo then joined the tapestry, half-rapping in Xhosa before flowing into English, speaking words of encouragement for the "African Child". It was a buoyant first piece, with all three JRP members contributing equally and captivatingly.

Their next item was called "Let’s Unite with Africa", featuring a stunning rap performance from Bongo, who showed himself to be an astute stage presence when his mic started giving problems and the dutiful sound engineer came to the stage to fix it. Yamkela’s singing was again the backdrop for Bongo's word traffic, and eventually Mwila joined in to bind the two together with his own voice. On "Children of Tomorrow", the following item,

JRP

Mwila left his drum to be closer to his two young partners, and it seemed Yamkela’s splendid singing felt even more emotive as it still steered the thread Mwila and Bongo needed to follow. At the end of their performance, they earned a delighted crowd response and a group of AmaZink regulars including Lwandile, Mr T, Khanyi, Tebogo and Pume gave them a standing ovation.

Adrian returned to the stage, playfully mentioning a mock-rivalry with Pieter: since Pieter had done a poem in Sotho, he would do a poem, "The Six Letters" in Northern Nigerian Hausa. It was a very short poem but well-presented by Adrian, with the translation on the screen. My Nigerian colleagues seemed generally pleased with Adrian’s recital of the poem, and from there he could move on to welcoming the next poet to the stage, who surely needed no introduction. Nondyebo Vuyo Mtimade, published praise poet and SLiP Slam Champion 2012 was enthusiastically described by Adrian as not only one of the most staggering performers we know, but also as a “down sister”, a reference to Vuyo’s unfailing humility and benevolence, which manifests itself regularly at the end of a phone call, when Vuyo is prone to saying “God bless” instead of “goodbye”, to which Adrian understandably pointed the question, “How do you hang up after that?”

Vuyo immediately phoned in the raw energy and sheer performativity and power that saw her win the Slam. As she took the stage, she already had a substantial portion of the crowd chanting and at that moment, Desiree Bailey walked in and stood somewhere at the back of the house — one giant had arrived just in time to see another. You’d had to have been beneath a beanstalk to have missed that moment. Suddenly, in the middle of the otherwise peaceful chanting, Vuyo exploded into action, throwing her authoritative voice in a loud cry and stomping her feet as if she was channelling right there and then. Here was our champion, elegantly dressed but showcasing so much strength that she’d have made Cuban soldiers feel unmanly. Within a few seconds, we saw what we didn’t see last year: a title defence. In November 2011, when the Final Three SLiP Slam contestants were given main event billing, the Champion, JC, could not muster the same level of intensity that had won him the First SLiP Slam only a month earlier. Not so with Vuyo. She attacked the stage, roaring like a lion and charging like a Cape Buffalo at a Scottish tourist, her title defence so ardent that from the crowd at the back, you heard Pume saying, “Easy, mama, easy”.

The translation on the screen read the poem’s title as “Burst, you Boil”, but the few words there were obviously not the sum total of Vuyo’s recital, which lasted a good few minutes — think of that scene in Lost in Translation where, after a two-minute diatribe to his American actor, a Japanese commercial director’s rant is merely translated into five or six English words. That’s how it was, and you’d hardly have needed the translation on the screen in any case, since your gaze was as locked as the Goodman Art Gallery. In Vuyo, possibly, there is an idea of what a younger, extremely loud Maya Angelou might have looked and sounded like — in other words, something of an insane alter ego to the younger Maya Angelou. Because Vuyo is emerging as someone as crucial to us as the Great Maya is to Americans; she strikes you with an assault of praise performance, beating any stubborn resistance out of you and doing that one thing that you still try to dodge: she makes you feel.

In English, which she unnecessarily bemoans as a language she is not comfortable and very limited in, Vuyo very articulately discussed the pains of translating her work, of making it available in English. She described her trouble in coming up with a poem for this event that she could deliver in English and, at 2am the morning before, she came up with "The Messenger", in which she expounded on the theme of the poet as a messenger to society with fire-in-the belly incantations and directives. There’s absolutely no need for her to feel at all restrained by English, even as she mentioned her lack of an English education: the language always comes from Vuyo’s core, she dances, stomps, screams,

Vuyo

hurls and charges it out, her body forming sentences that no book could capture. She ended off with a poem that was preluded by her telling us that she had no overwhelmingly happy events ("beautiful episodes") in her life to write about in her poetry, therefore there was always an element of sadness in her work. Yet, even as she said this she had the crowd in suspense for the simple nakedness around her words, so that when she got to reading her poem, even when she stumbled, it all felt connected, real, sincere and indispensable. “Tomorrow is forever”, she promised as she left the stage to a house applauding their champion.

Pieter then took the stage again, performing a provocative poem called "Gebed", with the translation, "Prayer" on the screen. In it he relentlessly criticised some of the conflicting attitudes to politics, race and moral partisanship present in most South Africans, with the week’s events sign-posted one way or another in the poem, but certainly not directing the prayer itself. It was a savage but uncomfortably affecting piece, far more than just another tirade tossed by an angry young man, and I expect it will do the rounds yet. The crowd caught Pieter’s wavelength and appreciated the poem. Somehow, the sound of his voice was slightly delayed between the mic and the speakers, and this helped give the performance an ominous layer, as if someone named "Evil Pieter" was actually reading the poem.

As one of the evening’s intended poets could not make it, the organisers quickly slotted in a replacement in the form of the trio SAN Records, surely one of the best names for a local group you could’ve imagined. The trio consists of cousins Andre and Stefans from the Northern Cape, and Nkaba from Botswana. Watching them perform was like reliving a Stormers game: it was a tale of two halves, except that, unlike the lacklustre Stormers, SAN Records ended much better than they started. Their first performance was a bit chaotic to say the least, with too much of a party-ish backing track not fitting well with the way the evening had been going, which was statelier and more relaxed. The incongruence and the sluggish performance testified to their being a last-minute replacement,

SAN Records

and you could see they were still very young — recipe for disaster, then? Not exactly; they ended this first item very positively, and you could relish seeing Alison and Pieter jiving to the beat, and also Tebogo, Pume and Lwandile were enjoying them. What had reached the crowd loud and clear, even through the noisy backing track, was their affirmative claiming of their San identity as well as doing their bit to remind the ignorant among us that the Northern Cape (and Botswana!) is actually on the map. The regular AmaZink performers liked this plenty, and called for more, not allowing the young trio to leave. Adrian then called them back to the stage for an encore. That’s where the artistry prevailed.

The matriculants (!) returned, eschewing a backing track for a simple but seductive beat on a drum, turning in a wonderfully arresting performance that showcased equally deft rapping skills from all three members and an unmistakable cultural proclamation. Quite unbelievably, they followed this up with their own reworking of that famous, annoying standard, "Jaloersbokkie", performing it quite fabulously in their mother tongue, !Xun. Give me their version any day and have Kurt Darren arrested while you’re at it; it wasn’t even his to begin with, anyway. SAN Records — what a surprise package they were!

Adrian returned to the mic and asked the crowd if he could do another poem, and with their consent he turned in a typically blistering take on "Colouredness" with "A Typical Coloured", arguing against a perception that being coloured is a stepping stone to either blackness or whiteness. You could tell it was an older poem, one Adrian probably wrote when he was younger, given the high-voltage and in-your-face style, but that didn’t take anything away from it. Clearly, Adrian’s been thinking in a certain direction and on the evidence of this compelling performance, expect more from him in the near future.

Jamala Safari then came to end the evening’s main event. Cape Town-based but hailing from the Eastern Congo, Jamala’s collection of poetry, Tam-Tam Sings, was published in 2008, the year, so Adrian told us, he first encountered Jamala at a poetry event he ended up winning. Clearly coming to Café Art with some clout, especially with all the festivals he’s appeared at, Jamala introduced himself modestly and immediately got down to business. Reading "Tam-Tam Sings", the title poem of his debut collection, he asked Mwila to accompany him on the drum. The rhythm of the poem was decisive, and Mwila instinctively knew his part, augmenting the words Jamala was reading by timing his beats and, in so doing, providing a pulse throughout. Jamala’s French accent gave the English words a crisp, alternative edge, drawing our attention closer to the flow of the poem.

"Bring Me Back to your Breasts" was his ode to Africa, a poem that tapped well into the work of the poets that took the stage before him, especially JRP. Reading the poem in English was difficult for him, he told us, as he seldom memorised his work for live performance, and seldom read his work in English. He clearly struggled to negotiate the at-times stolid translation, although this took nothing away from the iridescent quality of the poem’s typifying Africa as a nurturing feminine form. When he recited the poem in French, it was instantly more soothing, more translucent,

Jamala Safari

and it was allowed to breathe so. Afterwards, Jamala told us he’d not read the poem to an audience since possibly 2007, when he was still working on his debut.

Combining the mother-child quality of this poem with a touch of childhood reminiscing, Jamala took us into "The Calabash of my Grandmother", another evocative blend of natural imagery and a youthful, observational point of view, a strong underscoring of how nationhood is as much familial as it is familiar. Vuyo, sitting in the audience, smiled approvingly.

Jamala apologised unnecessarily for doing some self-marketing, telling us that his novel, The Great Agony and Pure Laughter of the Gods (astounding title — you could hear the crowd take that in for a few seconds), was due to be published in July and he’d be doing the rounds launching the book, which was also shortlisted for the Citizen prize. With that, he offered us his final poem, written for his younger sister, a caring, encouraging show of love to help overcome geographical distance. Once again, the importance of family was raised: in the system of African humanism, community is the heartbeat, and community is one way or another also described as family.

Adrian reminded us that there’d be a brief intermission before the Open Mic would start, and read out the names of those who would take the Open Mic, most of them names we should be very familiar with and one name, in particular, that would be hard to forget.

Open Mic

Our first Open Mic performer was Alison, who’d participated in every Open Mic this year and went as far as the third round at the Slam last month. She likes to bring the crowd in on her poetry, usually asking them to hold a chant down while she teases her words over it. At the Slam, she tried this to mixed results: one time it worked,

Alison

another time it didn’t. That not-so-successful second attempt at the Slam clearly bothered her suitably, and she decided to try the same poem again this time, asking the crowd to repeat, “I do—do you remember?” with rhythmic clapping. Over this steady base, she gave an intimate recollection, a description of closeness that skirted sensuality as much as it reinforced solidarity. This performance was highly successful and thoroughly engaging, laying the Slam Slip-Up to rest and surely putting Alison up for main event consideration at a future session.

Pume was next, and just as he did at the April Open Mic, humorously riffed on Alison’s chant, evidence not only of his ability to tap into an audience so quickly but also of his being a bona fide SLiP regular. Re-doing a poem he did in March and at the Slam, Pume’s shown the steady upwards curve of his progress and this was the one where he nailed it. His command was better, his meditations on the nameless,

Pume

globalised African were steered into the crowd with more assurance and his presence was more cemented. Well done, Pume.

Kgotso, also not too happy with his Slam performance, was yet another poet who wanted another crack at owning a stage. He acknowledged that he’d been working on his confidence and his booming voice hooked everyone in the house, and he was given considerable applause. Producing a stunning rap performance, Kgotso showed that he was able to overcome the tricky stumbles that inevitably occur when you go that fast, and he didn’t allow them to hold him back. Towards the end, he had one pronounced spill that threw him out for a few seconds,

Kgotso

but he collected himself and pushed on all the way, the respect of the audience very much won over. Adrian took the mic and told Kgotso, then already disappearing into the crowd, to provide him with his contact details, as he wanted Kgotso to take a main event soon. That’s what happens when you vary your game and work on your confidence — you get immediate results.

Our Queen, Khanyi, then announced that this would be her last Open Mic appearance, and you could see a big, bold "WTF" fly across the room — why on earth should this be her last, we all wondered? She said she took a leaf from Pieter’s book and would read her poem from her phone, requesting that the crowd chant “What Africa? Whose Africa?” when prompted, and she quoted Max du Preez (always a sound move) in this introduction. What followed was a provocative cry of empowerment, directed mostly at the youth,

Khanyi

and Khanyi did very well to urge young people to remember being regal, to remember former Queens and Kings and to aspire to such. The fires of Fanon were burning high in Khanyi’s words, herself, of course, a Queen when she takes the stage.

Pieter Botha, the Tom Cruise lookalike we’ve not seen since the Open Mics last year, made a welcome return to SLiP, reading an Afrikaans poem set in Cape Town and criticising the beautiful Mother City for its moral, industrial bleakness and its abject neglect of large parts of its population. This was about the hardest I’ve heard the usually affable Pieter go, especially as his 2011 poems were more celebratory, as if revelling in the very event of the SLiP Open Mic itself. This time around, he formed his lines sharply and expeditiously, and before you knew it, this long-overdue poem was done, leaving behind a firm impression and ample curiosity about Pieter. Some wit at the back of the crowd, a glass of whiskey in his hand, was suitably affected to respond, “I couldn’t understand him but I fell in love with that language.” Tom, er Pieter, has a follower, I do believe.

Ah, and then, there was Desiree. There was no way Adrian was going to let her merely hang back in the audience, not with the memory of her April performance still stuck in our heads, and not with her standing there in another killer jacket. You could see she had no idea and hardly expected to be called to the stage, but you could also see most of us expecting exactly that. She took off the black jacket and revealed the red top she wore underneath, looking as eye-catching and relaxed as ever, a soft yet sturdy appeal that one notices with Desiree. She courteously greeted the audience and expressed her surprise at being asked to perform a poem and then proceeded to share with us — in that moving, transparent way of hers,

Desiree

laced with innate sensory metaphor — how she couldn’t always understand the language of all the poems she’d heard earlier, but found a connection in the yearning to understand, and found the understanding therein. She explained that, while her poems spoke of the Caribbean, there were perhaps some associations with the poems she’d heard throughout the evening. We all knew there were, especially because there was a certain poem some of us were hoping she’d do again.

She recited "From the Shadows of the Sun", with which she had opened her set in April, and there’s little to be said here that wasn’t already said in the April report. Only, this time, Desiree’s delivery was even slower, letting the multifaceted weaving she was doing really hook, enthral, distress and arrest us. She followed that with "Haemorrhaging of the Native Young", the epicentre of her April presentation, and the excited gasps from those who remembered that night two months ago told you all you needed to know about how esteemed Desiree was. People who cried the first time they heard this poem cried again; people who’d looked at the video recording of that night a dozen times over still couldn’t keep up with the mind-bending twists and turns of the poem and its sheer ability to sandwich you between your own emotions. Because it was and always will be too much, it shall remain, I am positive, one of the greatest poems many of us will ever hear performed. A group of loudmouths outside the venue yapping away, completely ignorant of how quiet the rest of Café Art had become as Desiree stood at the mic, had some of us at the back furious: we would’ve gladly duct-taped their mouths, only we didn’t want to miss a second of Desiree’s performance. I mean, the rain falling on the streets outside even wore slippers and tried to tip-toe while eavesdropping, and there’s this lot arguing about the maxims of Bayern Munich. Brendan, the proficient sound engineer, had to snap himself out of the trance and hush the noise-makers. We were both grateful as well as selfishly thinking “better him than us”.

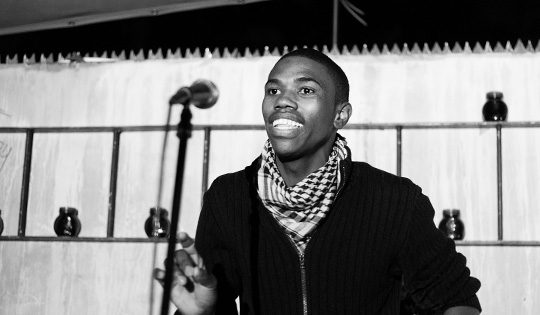

Desiree left the stage, leaving as victoriously as any other poet that came before her because she was as necessary, as profound, and as life-affirming. We didn’t clap as much as we put our mojos in the air and slapped the hell out of them with our hands. It was cruel to put another poet up after her. In the ‘60s, the Rolling Stones refused to play festivals where they were billed to follow James Brown, famously declaring: “You must be daft. You can’t put us up after that. He’s the show-stopper!” That’s what Ayanda was up against when he followed Desiree but our local poets are made of stern stuff, and he rose to the occasion, ending the night off with a spirited showing of stable rhyme and jaw-loosening oral gymnastics,

Ayanda

getting a workable aura going before ending somewhat abruptly. He’d done enough to bring the event to a close, although Lwandile was supposed to make an appearance, but had to leave early.

Thoughts

It was, all told, a complicated night to process. There was downright beautiful poetry, moments of pure exaltation and, by all means, more than enough proof that this was a wonderful initiative, hosting an Africa Day poetry event in Stellenbosch. What ultimately concerned me was that, in some of the South African contributions, there was something lacking. Only in some, but enough to raise one or two ponderous points. Of the local poems, both in the main event and the Open Mic, there was one contribution that transcended expectations and revealed an empathy, delicacy and sensitivity that is rare in South African poetry, more so in its gesture, in its selection and performance by the poet. Also, there were other poems that searched with communal discernments rather than individual ones and the poets sharing those poems, you could see, invested plenty of their beliefs there.

Other poems, I fear, seemed to be shifted out from events that occurred that past week in South Africa. To that end, they still tied into the perpetual self-obsession that you find in anything South African. Am I knocking the poets? No. Am I knocking some of these poems? No. Well, perhaps a little: it’s my feeling, and my feeling only, that this was a good opportunity for us to step back from our usual, insular bun fights (bun fights that won’t, cannot, should not, must not cease for a few more decades before we reach parity on whatever the hell we’re bun fighting about, else we won’t achieve anything, because we are an argumentative nation, we are emotional) and to use our poems to ask our brothers and sisters what their stories were. We invited them, yes, and we asked them to tell us their stories but we didn’t ask them too much in our own poems, did we? We didn’t interrogate, explore, get our hands dirty, feel them up, dance with them, seam or entangle ourselves. Our skills at being hosts could do with a bit of tailoring in such scenarios, when Soccer World Cups aren’t the issue. We were too busy responding to the latest big thing in our country and yes, you could as easily say such big things apply to almost any other African country, but we get a bit too self-involved to really explore that some days. Next week, I swear, it’ll be a 9-Gag picture of a bong being shared between Joe Slovo, Verwoerd and Ruth First — and they’re all dead. We’ll get heated, ceaseless bun-fighting just for the sake of bun-fighting, and forget that the world is watching us, almost as much as we watch ourselves. Put simply: from our side, I actually wanted to hear less South Africa on Africa Day; every day is South Africa Day to a South African, which is to say every day is a negotiation; every day is hard work that we are supposed to be immersed in doing, every single one of us. A slight respite to hear from our brothers and sisters, and only our brothers and sisters, was in order.

Especially after the kind of week we’d had, it was going to be hard for any South African not to come forward with thoughts about their country, but I maintain that it’s hardly different from what we always do: we talk about ourselves, all the time. Honestly, I found nothing new or invigorating in some of these local poems (technically fine as they generally were), because it’s what we do perhaps too much of, and it is why some reader’s post that week on NEWS24 (otherwise a haven for some pretty fucked up, discriminatory debates by people who have far too much time on their hands), in which she claims, “I Am A Racist” as a retort to both sensitivities around and abuse of the term “racist”, is probably going to find its way onto kids’ t-shirts soon. And that all came, in turn, from the melee made about the penis painting (and yes, I’m well aware that this report mentioned that quite a few times, too). All of that was in the air, and wouldn’t you know it, our contribution to Africa Day was to talk about ourselves. Again. We invite the rest of Africa for a braai but hog all the food and expect our guests to watch our conflict with ourselves about it, which is not very communal, not very African humanist. There’s much we can learn regarding empathy and grace here, and if I had to trace the missing element at Café Art that night, I’d say it was someone with age and wisdom, a poet that’s truly been there and done that. Most of the poets were young poets, the leaders of tomorrow, the strength of today, and all of them certainly brought enough of their own experiences to the fore. We know the value of youth. But we also know the hot-headedness of youth, when seventy per cent of what you say comes out strongly, sometimes aggressively, sometimes defensively. Through the main event to the Open Mic, there were four poets who channelled the sometimes more contained ways of elders, and they were the ones who were more mobile around the term “African”. Two of those were a little bit like the big sister and big brother, the ones leading us through more quiet but no less poignant fields. Not all elders are sage, are wise, are patient, set good examples; this is true. But we Africans seek out the guiding elders, those who know how easily a knife can cut the ties around a word like "tolerance", and how easily the knife belongs to us in the most ferocious exchanges, when you mean to save the world but end up sitting on it, sulking, or, worse yet, trying to run it.

Thanks

Last, but certainly not least, the expert services of Brendan, the master of sound engineering, must be acknowledged. The technical aspects of our SLiP events have been up for discussion of late because the quality of sound control wasn’t always consistent. Performers haven’t always felt entirely secure on the stage and it’s non-negotiable that artists have that security. Brendan brought his vast experience and dedicated professionalism to the party at Café Art, and the change was notable. With the house set-up being what it was, as well as a few over-excited performers, there were one or two minor glitches but these were to be expected, and Brendan attended to them each time in a heartbeat. More than just a technical crutch for us to lean on, Brendan took genuine interest in the poetry and made sure the interest stayed in the air, balanced and amplified. We hope to have him join the SLiP team in the near future.

It’s been a monumental 2012 so far for SLiP, and this last event can be added to that.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project