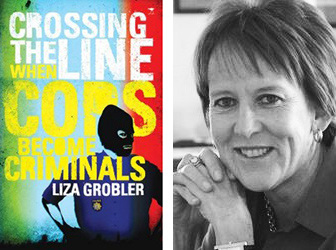

Crossing The Line: When Cops Become Criminals by Liza Grobler, Jacana, 2013.

“The video begins with a shot of a doormat and the bottom quarter of a door. A muffled, off-screen voice says in Afrikaans, ‘It is March 17, 2005. The video operator is Inspector Desmond Share. I am at Klein Welgevonden Estate, 21 Shiraz, Stellenbosch. The video begins.’” (Listen to an interpretation of the Lotz case by DJ Tjopper below - Ed.)

This is how award-winning author Antony Altbeker takes us to the heart of the crime scene of the infamous Inge Lotz murder in Stellenbosch, a mystery which was never solved and still haunts the South African subconscious. His writing is cinematic; he guides the reader in real time. “Two shadowed legs move into a frame. A hand swings the door open to the right, and a shaft of light falls onto a doormat before the camera bounces into the room. The cameraman steps over a yellow strip of plastic bearing the blue-printed legend ‘South African Police Service: Do not cross.’”

Police corruption throbs as a dangerous undercurrent in the story of Inge Lotz and her boyfriend, the accused Fred Van der Vyver, in Altbeker’s Fruit of a Poisoned Tree, his 2008 account of the murder and trial. It is also everywhere prevalent in Mandy Wiener’s 2011 bestseller, Killing Kebble, as the sensational murder of mining magnate Brett Kebble begins to join the dots of an underground network that includes former Chief of Police, Jackie Selebi. Our daily newspapers, from which these true crime stories take their cue, are filled with it.

Criminologist Liza Grobler’s Crossing The Line: When Cops Become Criminals, responds head-on to these allusions, which no writer in the popular market has been able to confront as thoroughly. It names and shames the various syndromes within the SAPS, taken for granted by most of South Africa, and includes invaluable firsthand accounts by police offenders (now incarcerated).

However, those lured by the cover’s subliminal promise of genre – a picture of a police officer wearing a balaclava – may be disappointed. This book does not begin with police tape and distant sirens. The exhaustively researched account is clear about its aims: “This book’s only focus is on the crooks and criminals within the SAPS.” Grobler’s is a presentation of straight facts and statistics, a valuable and comprehensive handbook about the extent of the problem, where it started and how we can begin to solve it.

A book like this has surely never been more relevant in the new South Africa, after the political appointments and subsequent dismissals of Jackie Selebi and Bheki Cele, after Marikana, after the horror stories of the death of service delivery protestor, Andries Tatane, and two incidents of men being dragged behind police vehicles – not to mention the ubiquitous acceptance of bribes, misspending of funds and nepotism. Using the New York Police Department, London Metropolitan Police and the New South Wales Police Force of Sydney as favourable models, Grobler is able to identify some of the roots of the SAPS’s problems, including denialism at the top, the lack of checks against corruption (the SAPS anti-corruption units were dissolved in 2002, the Scorpions in 2008), the marriage of the force with politics and the lack of ethics and integrity-training for rookie officers. As Grobler points out, rookie officers have only the SAPS Code of Conduct for guidance, in which there is only one vague line pertaining to corruption: “and work towards preventing any form of corruption and to bring the perpetrators thereof to justice.” But what could this mean to someone who has never learnt what corruption is?

For those who have suggested, as Mike Nicol has done recently, that true crime is less a means to understand the country’s malaise through its underworld than it is a commercial answer to a growing rapaciousness for grim and gory details feeding reactionary sentiments, this book presents a counterpoint. Grobler’s language is sober, her suggestions practical, which makes sense considering that it is an adaptation of her doctoral thesis. As such the volume of its facts and figures can be overwhelming: “The ICC has a staff complement of 425 – there are 121 investigators (including investigators, deputy senior investigators and senior investigators). It uses police resources for investigations, but remains in charge of inquiries, giving the investigators daily instructions,” she writes in her first chapter. This style is occasionally shot through with a one-liner like “a fish rots from the head.”

It’s a far cry from the dramatic narrative techniques of Killing Kebble and Hanlie Retief’s Byleveld: Dossier of a Serial Sleuth, both of which have sold over 60 000 copies. On the other hand, while Leon De Kock warned readers that Fruit of a Poisoned Tree’s delicate analysis of South Africa’s justice system will require “a fairly grim kind of concentration”, this did not detract from its considerable success and sales have now reached 11 000.

“We believe this book is long overdue,” said Jacana spokesperson Neilwe Mashigo. “2013 sees the prevalence of police corruption reaching an all-time high and we need to get citizens informed.” However, good faith does not guarantee that people will pick up the book and start reading, and Mashigo admits that they would like to see more books leaving the shelves.

Perhaps the difference is simply the human element of narrative, something like Wiener’s portrayal of Selebi during the lunch breaks of his trial: “He would be bent over, his elbows resting on his knees, his hands clasped together and his droopy, yellow eyes peering down his nose. On many of those days he would beckon me with a jerk of his head and I would sit with him as he ate his lunch of one apple. I never saw him eat anything other than that and when I enquired why, he would pull up his nose and simply say he had no appetite.”

Nonetheless, while Grobler's book is no easy beach read, it is guaranteed to appeal to a South African reading public that yearns to understand the strange and disturbing aspects of their society.

-

Here's DJ Tjopper's interpretation of the Inge Lotz case, as promised:

A true story of murder and the miscarriage of justice by Slipnet on Mixcloud

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project