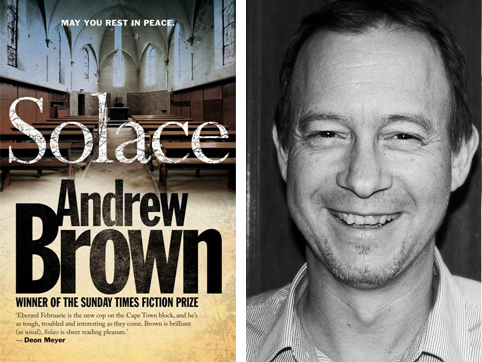

Solace by Andrew Brown, May 2012, Zebra Press.

The title of Andrew Brown's latest novel, Solace, suggests the idea of comfort and consolation, perhaps even relief, or a form of safety from danger. Those familiar with practising advocate and police reservist Brown's oeuvre would know that the writer is adept at titles that offer a “cold” form of comfort: Cold Sleep Lullaby and Refuge both deal with the lives of those deemed foreign or threatening due to their refugee or migrant status. After having established involvement with an "other" – which is often represented in encounters best described as traumatic – these novels gesture towards a sense of closure or comfort that is precarious at best, still fraught with unresolved entanglements.

Under the wide rubric of "crime fiction", Brown opens up a space to confront serious socio-political issues, but the author resists the sense of closure and neat conclusions often found in the genre as a whole, and in some of the local crime novels on offer.

At face value, Solace sees Brown operating on terra firma. Set in and around Sea Point, it takes its cue from Margie Orford in that a young street child, Coenie, is brutally murdered, his heart partially ripped from his body. The boy is laid to rest in a synagogue, draped in a Muslim prayer robe. As the tension arising from the murder grows between Jewish and Muslim factions, Brown’s writing also follows Deon Meyer: his protagonist, Eberard Februarie, acts as a cultural mediator (much like Meyer’s Bennie Griessel) while facing down his demons with the bottle. Februarie is in far worse shape than when we last saw him in Cold Sleep Lullaby.

Brown is a shrewd writer, and Solace sees him firing on all cylinders. Where Refuge has Brown venting at a gated bourgeoisie blighted by seeming indifference to the predicament of the city’s underclass, Solace is more ambitious, more global in its reach: it is an exploration of religion, probing the three monotheisms of the Mother City, and it uncovers intolerance and fundamentalism in a study of “the length and the depth of the human condition itself” (6).

Without ever making it explicit, Brown takes liberties with very recent, recognisable historical events, and recasts them around a historical moment in the not-too distant future where religious tolerance is low and a wave of conservatism has taken hold across the world. Accordingly, he situates his cast of characters in a local environment interpenetrated by a wider global order.

Before (re)introducing us to Detective Inspector Februarie, we read of the “propaganda” and “posturing” that accompanies the reporting of news worldwide. The mechanism of establishing connections between seemingly disparate layers of society on a global level, and the deliberate attempt to be even-handed in handling sensitive socio-political issues, underscores Brown’s overarching attempts at creating a less parochial sense of community in the novel as a whole.

For example, the novel mentions the counter-offensives of the Israeli Air Force in Lebanon aimed at Hezbollah strongholds that destroy a school and a tinned food factory inside Lebanon (5), but we also hear of the “intractable” will of the Israelis. In an interesting variation of the connection between global and local, the determination of the Israeli Air Force is offered as counter-example to an SAPS “crippled by changing political tides”, where nepotism is “rife” and each new commissioner promises “an end to corruption”, “only to be removed, eventually, in scandal” (6).

A mere two pages later, we read of “Anti-Islamic protests in Paris where Muslim headgear was burnt outside a Paris mosque”. Here, Brown is clearly drawing on recent headlines, while at a later stage the “populist revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya” (57) also feature. Conversely, Solace imagines a moment in the near future where new American President Harvey promises America a “return to traditional family values”, shortly before the “Conservative Bill on the teaching of creationism in American schools is due to be presented to the legislature” (8). Such moments are not limited to the aforementioned, and they lend Brown’s writing an invigorating socio-political bite that might serve as an example to others contributing to the genre.

In Brown’s South Africa, the Minister of Police is the ambitious Dupisani Favi, married to the sister of the Minister in the Presidency, a self-made “politician” “championing the new Social Values Act, a cornerstone of the government’s populist strategy to rebuild its power base” (7). Zwelinzima Vavi? In this future state, South Africa has banned the burka, a Captain Simelane (Menzi?) from National Intelligence is intent on protecting “Christian Africa” from toxic others, and the Social Values Act has given government “the right to scrutinise the beliefs of others. To decide what constitutes acceptable religious practice” (59). Brown doesn’t miss a beat, throwing in the slaughter of animals in residential properties by Nigerians, the “gentrification of traditional malay area[s]”, and the conflict between Roman and Sharia Law for good measure (115).

Brown’s Eberard Februarie is an inspector with some eighteen years’ experience, “trapped by racial quotas” that hold him “beneath the surface of the water like a bully’s hand” (7). His “self-destructive behaviour” renders him a self-loathing, alcoholic outsider who behaves in typically hard-boiled fashion (7). Sobriety is “unimaginable”, and his wife Tanya finds solace in “spiritual promises” (10). After their separation, Februarie considers suicide, but that is “never a comfort he had seriously embraced” (140).

Februarie works in a provincial office of the Serious Crimes Unit, the “filing system for human depravity” (8) where he encounters heinous deeds such as the murders of young albinos for township muti. In order to cope with his reality, Februarie forges a tentative yet tender relationship with a prostitute called “Angel”, or Laetitia Apollis from Bishop Lavis. For Angel, Februarie is “a protector, a stable haven” (13). While Februarie struggles to make sense of the murder of the young boy, his relationship with Angel and her pimp Marnie “Lastig” Solomons allows Brown to traverse various elements of the city’s underworld, making for gritty reading.

Brown peoples his novel with a wide-ranging group of acutely observed characters, who come to life in their interactions with each other. On the case with Februarie is the unassuming Thabani Makosi, who also happens to have a Jewish ex-girlfriend, and Jewish social worker Yael Rabin, with whom Februarie forms an attachment. Their interactions offer the kind of generic romance often found in crime fiction, but their relationship is layered, unforced, and integral to both plot and character development.

Amid the banality of what the novel accounts for in human sacrifice, child murders, evisceration, whoonga (a “toxic cocktail” that mixes “antiretroviral drugs, crystal meth or cocaine, and rat poison”, 50), Brown raises into prominence the mysticism and sacred aura of the Jewish faith in particular. Rabbi Jonathan Levitt speaks to the prejudices and offences that have accompanied manifestations of anti-Semitism as Februarie learns more about the particulars of the Jewish faith in the sacred objects of the Sefer Torah (the Torah Scroll – never handled by those that work with it), and the shema, the central prayer in Judaism taken from the first words of Deuteronomy 6.4, the “cornerstone of monotheism” (40).

When Februarie attends a service at shul to commemorate Tisha B’Av, the commemoration of tragedies of the Jewish people going back many centuries, he is struck by “an instant exoticism” that evokes a “visceral response ... [A]s if he had travelled across an immense plain to reach a place of infinite otherness” (125). This observation reminds us just how powerful and immediate religion can be, and reads an affirmation and celebration of both community and difference.

To complement the novel’s exploration of some of the rituals and practices of the Jewish faith (there are many covered in the novel), the story shows two divergent sides of the Muslim faith. They come in the form of radical militant Saliem Achmat, trained in Afghanistan, and imam Abdullah Toefy, a moderate chairperson of the Muslim Judicial Council, who sits with Rabbi Levitt “on an inter-faith forum” (58). Achmat is an intense, fanatical presence, and the two older religious leaders in Toefy and Levitt counterbalance his extremism. The most deplorable but also most one-dimensional character (and stock element) in Solace is the Christian fundamentalist Pastor Isaiah Jackson and his One Church. Jackson’s zealotry and bigotry soon grow tiresome.

The novel is intelligent in its exposition and keeps one guessing. There are a few red herrings in the course of the narrative; Brown has fun with a minor Russian thug by the name of Andrew Kolchensky. On the other hand, Brown shows how the powerful use the innocent – people like Josh Shimansky, the mentally challenged son of the shul caretaker Arthur Shimansky – as pawns in deplorable acts of abuse. The novel’s denouement oozes with confidence; to say more would be a crime.

In Solace, there is no place for “horrified titillation” (23). Rather, it is an incisive, compassionate call for the appreciation of community and of various freedoms (of religion and expression, particularly). Although the pathologist Rademan informs Februarie at one point that ours “is a comfortless world” (40), Brown shades his own call for tolerance and understanding with the need to recognise human beings as the fallible torchbearers of such ideals.

Solace never strays far from its belief in the human potential for both terrible and humane acts, a recuperative gesture if ever there was one. It is much more than just a stock-in-trade work of genre fiction; rather, it is a work where the “possibility of renewal” (250) is always somewhere on the horizon, often just within reach.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project