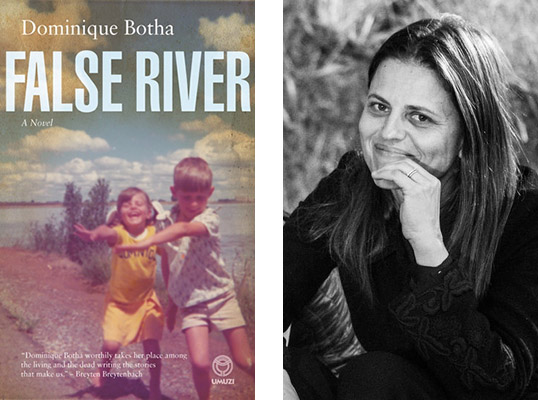

False River by Dominique Botha, Umuzi, 2013.

Dominique Botha’s debut, False River, is a beautifully told South African story. Seldom has a prose style so captured my imagination and admiration. This is one of those books that you read with a pencil in hand because you want to place a mark in the margin next to phrases that haunt you.

But what is False River? The book’s cover tells us that it is a novel, yet this lyrical account of family, place and time is very much a memoir. Dominique Botha the author appears as Dominique Botha the character; it is Paul Botha – the writer’s brother, ons mooiste en ons slimste – whose life and death provide the narrative arc.

False River is perhaps best considered a novel in the same way that Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers are considered novels. Like those archetypal examples of the bildungsroman, False River is memorable precisely in its exploration of the very concept of memorability: what we have before us is a feat of recollection, yes, but also of imagination, evocation and, paradoxically, of submission. In order to write powerfully and unforgettably, a skilled writer bows her head and becomes utterly vulnerable.

In young Dominique, we are given a portrait of this strength-in-vulnerability. Relegated to an English boarding school in Natal, Dominique astral-travels home in her dreams, though she only ever reaches the peach tree before the sun starts rising and she is pulled back to the institution she hates. It’s the kind of school where one girl shows her dislike of another by defecating in her suitcase. Dominique adopts the mode of protest most favoured by teenage girls: starving herself.

In False River, the writer summons the memory of her northern Free State family farm, Rietpan, with longing and that rarest of qualities, an unsentimental nostalgia for time lost. Botha’s rendering of the landscape places her alongside Antjie Krog (who grew up, as it happens, only four farms down the same river). Like Krog, Botha writes prose in a way that honours the poet within. As Paul Botha, her brother and the writer manqué, asserts: “your place of origin imprints on you. Writing is a relic of where you find yourself.”

If it is love of the farm that supplies the book’s principal theme of homesickness and homecoming, then it is Dominique’s love for her maverick brother Paul, and her evocation of their joint and separate growing up, that provide the novel’s action and indeed its raison d’être. In this sense, False River is a work of profound psychological expiation: not just a sister’s mourning or a sister’s tribute, but a delicate tracing of the community and genealogical dynamics that can turn any loss, however personal, into a political parable, a national elegy.

None of this makes the book a heavy read, however, since the narrative is leavened by Botha’s coolly ironic telling. She writes what she sees and hears, without apology or embarrassment for her own South Africanness, and without any of that heavy straining after political significance that makes some novels such a bore.

Of all the voices she hears, I love her father Andries Botha’s best. After watching the infamous “Rubicon” speech on TV, he says: “Hierdie fokken Botha maak ons hele familie se naam gat,” which causes “Mrs Swanepoel [to clutch] the collar of her appliqued blouse.”

False River is lit up with Pa’s expostulations. When sensitive Dominique is pursued by the angel from the family graveyard who speaks to her in the voice of an owl, Pa’s exasperated “in god’s name stop this crap” is the universal cry of the exasperated parent. Even when his oaths are recorded in English, it is as if we are hearing Pa vloek in his original Afrikaans. Oom Koelie, for example, who provides “racist predictions of doom” is, in Pa’s estimation, “a jovial cunt”.

Pa has built his workers proper houses and a school; Ma refuses to use the “Whites only” entrance to the bottle store. Her office door is always open to supplicants seeking money for funerals or school fees. Both are intimately caught up in the lives of their workers; they object to Apartheid; they speak out against Bantustans. As a result, there are few families in Viljoenskroon who will entertain them.

We learn these things by-the-way, without Dominique Botha ever trying to valorise the actions of her parents. Like them, she suffers the complicity of the listener, the one who hears and hates the racist tirade without being able to blast it off the face of the earth. The visiting dominee, who doubles as a diamond smuggler, refers to black people as “die swakkere broeders”. A girl in Dominique’s class is breathless with excitement that “a kaffir hung himself from one of the trees on the parade ground. Isn’t it wonderful? Now there is one fewer of them.”

The Bothas of Rietpan are part of that small and often unjustly maligned grouping of white South African liberals, the ones who ask for a “Smuts cookie” rather than a “Hertzoggie”, and who try to practise an uneasy egalitarianism in a way that goes beyond merely handing out largesse. Not an easy thing to do when your title deed stretches back to the Great Trek, and your family still recalls the scorched earth of the Anglo-Boer war.

Out of this union of idealists and this history comes a firstborn son, Paul Botha the sixth. He is uncomfortable with privilege right from the start, but his tragic destiny is, like Hamlet’s, shaped both by genes and by Zeitgeist. Paul Botha suffers both from an innate, “otherwise” personality and the cursed spite of being born in a country where the time is out of joint. How to put it right?

Like the Prince of Denmark, Paul’s actions sometimes seem like mere gestures (spending his entire salary on taking bergies to the Mount Nelson for dinner, or scrawling “Suppress Shakespeare” across a UCT exam paper). But at other times, as when he slits his wrists while on compulsory military service and ends up in DB for “damaging state property”, or in 1987 writes a beautiful poem containing the lines “come/come with me/to the bareback veld/ where the wind will/distilling, blow/ you into me/me into you”, he shows true revolutionary stature.

The rapport between defiant brother and compliant sister gives Botha’s memoir the symbolic and weight-bearing foundation that fiction demands. His friend Lew describes Paul as

the archetypal beat person. He embodies the nature of the natural outlaw. They are always photogenic. Outlaws always know how to hold a cigarette. He’s the guy who actually does get to fuck all the waitresses … He almost wants to force people to live in a true way.

When the same friend asks Dominique how she would describe herself, she admits that: “My years stacked up like an anaemic resume of conformity in my mind.”

While Dominique “wished that Ma and Pa would vote for the National party and go to the Dutch Reformed Church”; Paul asks: “For my birthday, I would like the school to burn down”. Whereas Dominique becomes head girl of Senekal Primary, wins a scholarship to a fancy English girls’ school, bakes pies for the local tuisnywerheid and obsessively practises the piano; Paul joins the End Conscription Campaign, gives the black power salute on Hilton’s stage, pees in the school fountain and, when dagga-smoking gives him the munchies, eats all his sister’s pies. Though both siblings drop out of school, Dominique turns to good works – starting an embroidery business on the farm – while her brother struggles and eventually fails to live his life outside the capitalist system he so despises.

False River is a multi-layered novel, a slow but rewarding reading experience. If Hamlet had had a sister, she might have written a story like this.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project