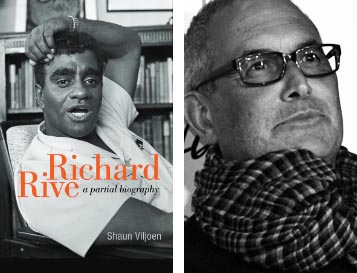

Richard Rive: A Partial Biography by Shaun Viljoen, Wits University Press, 2013.

Richard Rive, best-known for his novel ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six, and perhaps also for the gory tabloid details of his murder, was a sharp-tongued, posh-voiced, larger-than-life character who relished the public platform afforded him by his teaching career. By his own admission ‘grossly over-educated’, he took pleasure in berating stumbling pupils with barbs such as ‘Your mother doesn’t love you’ or ‘Have you no ambition?’

Yet, despite his apparently derisory stance, time and again Rive left the comfort of his increasingly middle-class world to nurture, defend and mentor the often beleaguered youth of South Peninsula and Athlone High. On one occasion, after witnessing protesting pupils at a school neighbouring Hewat College under bombardment from the riot police, he found himself clinging to a wire fence and screaming abuse. His own response astonished him.

He was more at home with the written word. The body of fictional work Rive produced between 1954 and 1989 – twenty-five short stories and three novels – put him at the vanguard of South African protest writing, which slammed down gritty realism and furious polemic with equal measure.

The earnestness of his stories was at odds with the Oscar Wilde-like flourishes of his personality. After Emergency and African Songs were banned, he archly observed that he had become ‘part of a small elite of South African writers not allowed to read their own works’. When asked by an interviewing panel what he would do if he didn’t get the Fulbright funding he was applying for, he quipped: ‘Then I’d like to see who does!’

Although Rive clearly drew on his District Six origins and his experiences of teaching at institutions, like Hewat, that were loci of political foment, he was in at least one other sense not ‘an autobiographical writer’ (a term I place in scare quotes because although it is widely applied, its meaning is ill-defined). Rive’s characters look like him, ‘attractive’ with ‘wide black eyes … dark brown, with heavy, bushy eyebrows and a firm jaw … in Durban he could pass for an Indian’; like him, they suffer the indignity of racism, sometimes even from lighter-skinned family members. Yet in one important sense Rive’s characters are distinctly unlike him: they are heterosexual.

Among the many strengths of Richard Rive: A Partial Biography is Shaun Viljoen’s understated, assured, queer re-readings of Rive’s short stories in particular. In the story ‘Riva’, for example from Advance, Retreat,the name of the odd-looking, camp-acting, self-styled queen called ‘Riva’ is read as a feminised version of Rive. The 1970 story ‘The Visits’ is decoded as an ‘intensely personal reflection on frustrated, unspoken desire’. We are able to understand why the love scenes between Andrew and Ruth in Emergency seem less believable than Braam’s encounter with a prostitute: Rive the writer felt more at home with the illicit encounter of strangers than with the intimate meeting of conventional partners. Read through a queer lens, Andrew’s closing reflection, ‘maybe I’ve been running away from myself’ loses the cliché, becomes exquisitely poignant.

As Viljoen points out in his cogent preface, queer readings would have been condemned by the comrades of the protest era. A sometime acquaintance, and eventually even dinner guest of his subject, Viljoen is particularly conscious of betraying a man who was ‘silent in life and fiction on questions of homosexual desire’ and generally ‘tight-lipped about sexual relationships’. Given these qualms, the reader feels like cheering when Viljoen stoutly asserts that ‘this is my version of Rive’s life, not his’.

There are other ways in which this was a difficult book to write. Viljoen knew Rive in the 1970s through NEUM (Non-European Unity Movement), but they were not friends. Viljoen didn’t admire Rive’s work and found him pompous. But joining the staff of Hewat College meant that the two men worked alongside one another from 1987 to the time of Rive’s death. In a touching acknowledgement of what it means to engage with the primary materials of another person’s life, Viljoen describes how Rive grew in his estimation – ‘I began to grasp his immense courage, drive and vision,’ he says.

Viljoen’s postmodern lens allows him to focus on some of the unsettling complexities and perhaps complicities in this life-writing project. In addition to teaching on the same staff, and collaborating in a stage version of ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six, there are other overlaps between Viljoen and his subject. Both were classified ‘coloured’, both styled as ‘coloured intellectuals’ who ‘felt compelled to assert western cosmopolitanism in resistance to balkanising tribal racism’, both uneasy with the label ‘gay’. The smallness of Cape Town’s society even means that in Richard Rive’s matric photograph, the biographer’s father, Ian Viljoen, kneels to the left of Rive.

Viljoen’s interpretations of the photographs spread throughout the text, most by George Hallett, a pupil and lifelong friend of Rive’s, are particularly compelling. This is partly because of the poses Hallett captures, and partly because Viljoen reads them so insightfully. The cover photograph, for example, shows a

comfortable, confident, even cocky man in a typical gesture of his, arm over the head as if to frame himself as he is framing his words, fingers containing the temple in a gesture associated with thought. He is seated and, with his eyes overlined by those distinctive fulsome eyebrows, he stares directly at the photographer, his protégé, and beyond at us, not smiling but holding forth, claiming a point, loud, yet, as is the way of a photograph, silent and therefore forever ambiguous.

Rive, like many writers, tried to leave behind the version of his own life that he preferred. In Writing Black, he wants to come across as an established mentor of other writers such as Arthur Nortje (‘I was hard on him, forcing him to substantiate the use of every word he had written’) and Ngũgĩwa Thiong’o (‘Ngũgĩ and I sat down at his desk to work our way through his short story … The bell rang for lunch but he insisted that we continue’), as well as an established member of a literati that provided introductions to Bloke Modisane, Casey Motsitsi, Todd Matshikiza, Lewis Nkosi, Es’kia Mphahlele, Jack Cope, Uys Krige and Ingrid Jonker.

By Rive’s own account, he was cosmopolitan, urbane, at ease with himself and with others. But as he admitted, some aspects of his life were ‘locked away in that private part of my world which belongs only to myself and perhaps one or two intimates’

It’s a first rule of biography that there will be holes: letters burnt, conversations never recorded, sources not contacted or found. The biographer works, perforce, with a net. As Julian Barnes writes in Flaubert’s Parrot:

You can define a net in one of two ways, depending on your point of view. Normally, you would say that it is a meshed instrument designed to catch fish. But you could, with no great injury to logic, reverse the image and define a net as a jocular lexicographer once did: he called it a collection of holes tied together with string.

You can do the same with a biography. The trawling net fills, then the biographer hauls it in, sorts, throws back, stores, fillets and sells. Yet consider what he doesn't catch: there is always far more of that. The biography stands, fat and worthy—burgherish on the shelf, boastful and sedate: a shilling life will give you all the facts, a ten-pound one all the hypotheses as well. But think of everything that got away

Viljoen manages and respects the gaps that Rive was keen to maintain. He acknowledges that the trial in which 22-year-old Vincent Aploon and seventeen-year-old Suleiman Turner stood accused of murdering Richard Rive with a meat knife threw up a number of explicit photographs and revelations about the nature of Rive’s sexual activities with these and other young men who visited him. Viljoen also briefly refers to rumours that Rive occasionally forced himself on attractive male pupils. But he goes no further with this salacious material.

What he gives us instead and, I think, more productively, in his ‘partial biography’, is a vivid sketch of a man whose writing emerged from a mass of contradictions. Rive was happy to write to Langston Hughes about the ‘slum’ he grew up in, as long as Hughes understood that ‘I come from a cultured family’. Rive mocked the University of Cape Town for its Eurocentric syllabus, but loved Dylan Thomas and John Steinbeck above all others. He could as easily be found listening to an orchestra or attending a political meeting. He wrote of District Six but felt completely at home in Oxford.

Rive comes closest to admitting these contradictions when he writes rhetorically: ‘I am discussion, argument and debate. I cannot recognise palm-fronds and nights filled with the throb of the primitive. I am buses, trains and taxis. I am prejudice, bigotry and discrimination. I am urban South Africa.’

Richard Rive: A Partial Biography is a scholarly work (the acknowledgements read like a Who’s Who of South African literary studies), filled with critical insights into Rive’s work and political and literary context. Yet it is also a highly readable biography of a man who wanted what so many of us still want: to be allowed to be both wholly local and fully global.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project