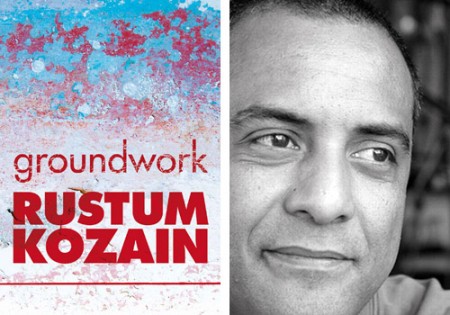

Groundwork by Rustum Kozain, Cape Town, Snailpress /Kwela, 2012

One of the images from Kelwyn Sole’s poetry collection, Absent Tongues, which lingers in my mind, is that of the garden spray:

Late-rising moon:

a sprinkler, forgotten,

sighs to and fro

across the lawn

(“Poems of the Sea for Me”)

Consequently I was intrigued to see that Rustum Kozain also uses this image:

while outside the sprinklers

drizzle softly in the garden

(“The Adoration of Cats”)

and

the unending ticker and swish

of a sprinkler outside

(“Christmas Eve”)

Both poets effectively employ onomatopoeia, with Sole’s “sigh” and Kozain’s “drizzle”. A sense of movement is evoked by both poets: “to and fro”, “ticker and swish”; and a sense of time: “forgotten”, “unending”. I am labouring this point for a reason, since the collections share other similarities: both books are almost exactly of a length (Sole’s 76 pages, Kozain’s 78 pages), both have three-part structures, and they share a number of other distinctive characteristics like frequent bird and water imagery, a profound sympathy for the poor (with its concomitant aversion for the rich), and the same setting: Cape Town.

I suddenly recall schools of poetry that have come and gone over time: The Movement, for example; and The Beat Generation; The Confessionalists; The Martian Poets; and so on. Are we witnessing a new School developing around Kelwyn Sole and Rustum Kozain?

“Groundwork” is an apt title for this anthology. It’s a strong compound word, two stressed, no-nonsense monosyllables. It recalls Dan Wylie’s “Road Work”, Seamus Heany’s “Digging” and, above all, N.P. van Wyk Louw’s “Beiteltjie”:

Toe onder my tien vingers bars

Die grys rots middeldeur

En langs my voete voel ek

Die sagte aarde skeur,

Die donker naat loop deur my land

En kloof hom wortel toe –

So moet ’n beitel slaan

Wat beitel is, of hoe?

If groundwork, literally, is the solid base on which a structure is built, it seems to me that Kozain’s figurative use of it is what most distinguishes his poetry from Sole’s: his profound interest in his Muslim Afrikaans roots. Another distinction is between Sole’s largely “positive” restiveness and Kozain’s largely “negative” melancholia.

I get the impression that both these poets’ ideals (Communist?) have taken a drubbing by the outcome of South African Independence: the unsteady decline from Mandela to Mbeki to Zuma to … Malema? Those of us further north had our political ideals eroded into scepticism, if not cynicism, some time ago. We have learnt the hard lesson of history, that Davids are Goliaths in waiting.

Rustum Kozain would probably have identified himself with Black Consciousness (particularly under the influence of his mentor, Kelwyn Sole) before Independence and during the all-too-short Mandela governance; but in these poems of grief, of loss, and of regret, he has returned to being a brown man in the rain, running, like his father’s generation:

from black vandals into the past

and finding himself drawn life-large

in the grudging cross-hairs of white vandals

(“Storytelling”)

But brown is a warm, earthy colour; brown is the future; symbolically it is unsuitable for these poems. These poems are blue – not like the eyes of H.F. Verwoerd, but like the songs of African slaves. And they are black – not like the skin of Steve Biko, but like the dog of melancholy.

Occasionally the gloom is lightened by short, incidental pieces like “For Michael Jackson”, “In Bed with Jimi” (Hendrix), “The Lover Surprised”, and the delightful “In Mexico”:

In Mexico

I dream

the sunflowers sway.

In a small town

a man grows

into a boy.

But gloom (gloaming) implies light. When Thomas Hardy’s critics chastised him for being a pessimist, he replied to them in his poem, “In Tenebris 11”: “… if way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst.” Hardy, like all great lyric poets, understood, if not approved of, the necessity of opposites, and it is in this spirit that that I read and celebrate the work of Rustum Kozain.

“Regret” is clearly a significant poem for Kozain because he foregrounds it – puts it in the space where introductions or prologues go, outside the three sections. His creative imagination sees regret as a “slow vulture” that is always “too late”. The “too late” theme is as pervasive in lyric poetry as the ubi sunt and the carpe diem. Human nature is perverse in that we seem to appreciate something (or, more poignantly, someone) only once we have lost it. Youth, we say, is wasted on the young. The vulture of regret, like memory, operates simultaneously in the past and the present, it “comes too late” and it “came too late” – too late for the right lover at the right time; too late for the right political ideology at the right time; too late for

… something of this sea –

its cold and darkening deep –

in the human heart, in me…

(“This is the Sea”)

So the persona – “I am that regret” – dies into the shadow of memory where the “conjuring” wordsmith can summon nothing more than a “flinch” – a shrinking away from.

But the persona’s regret is Kozain’s poem, his artistic achievement. As Tennyson puts it:

My regret

becomes an April violet,

and buds and blossoms like the rest.

(In Memoriam)

People tend to find vultures, like all carrion, disgusting creatures. But when you start considering the symbolism of this bird, you find that it is mostly positive. As a consumer of dead things, it is given an important role in the process of renewal. Outside human consciousness there is no life and death, there is simply one form of energy metamorphosing into another. So Kozain’s choice of a vulture to reify regret is more complex than it first seems.

Something similar is at work in “Kingdom of rats”, an astonishing poem, also full of regrets:

Father, try as I do, I can give

no full tongue to this verse:

a stingy square

where Yeats and fucking Eliot

still ricochet from walls of stone.

These aridities. Where no one

will enter for rest, my verse

no garden. No sound

of the autochthon.

He regrets that his thoughts, his feelings, and therefore his poetry, are derivative, corrupted by the Western canon. His rats drag their bellies like Eliot’s rats in The Waste Land. He confesses this to his “Father”, a word that stands for more than his biological father, whom he honours so beautifully in his first volume, This Carting Life – a word that reaches, I think, deeply into his Muslim heritage. It precedes his Marxist ideology: “Father. Comrade. Whoever you are”.

There are very real rats running through this poem, scattering droppings, dying from warfarin poisoning; and there are very metaphorical rats in this kingdom – the poor, those shrugged off by history, i.e. by the shithouses in power – the ones who cruise around in BMWs with tinted windows, and poke themselves stupid. The person himself is part rat:

In some rented room –

the basin stained like a smoker’s teeth –

in its crawlspaces where I hunt,

in cupboards I root ...

So, while we flinch at the literal rat imagery, we endure the figurative rat imagery. We are simultaneously disgusted by and sympathetic to urban poverty. Like the vulture in “Regret”, the rat is a complex symbol of ambivalence. We pity the homeless burning plastic “against the cold”; we recoil from the rodent:

… fighting off its death,

blood smears on the linoleum.

Rustum Kozain flays himself in this poem. Even the two epigraphs seem to single him out:

Everyone hates a bore

Everyone hates a drunk

Everyone hates a sad professor

I hate where I wound up

(REM, “Sad Professor”)

Well, the only thing I know about him is his poetry, and he certainly is not a bore!

Three of the poems in this collection have eponymous titles, with slight variations. “Groundwork” uses the word “loss” too frequently; “Groundwork X” makes me weep, which I resent; “Grondwerk”, in the immortal words of Goldilocks (commenting on baby bear’s porridge), is “just right”. Kozain loves the image of water running over stones; once he even says it in Hebrew (“The Blessing”); in this poem the stones are cherished Afrikaans words from long ago, and the water is the poem itself, which runs over these words:

Granaatboom in an aunt’s backyard;

behind the pigeon coop in the big yard

that holds the hanslam, mischievous

eight-year old twins smoking wildedagga;

and, from the kitchen, gemmer, anys, kaneel.

This is not the Afrikaans of Die Taal Monument; it is the Afrikaans of the fishing boats and the vineyards and the townships – kombuistaal. This is the Afrikaans that Kozain’s ancestors created, long before it was written down, long before it was appropriated, after the Second World War, by the architects of Apartheid. And this is a most important aspect of what makes him, despite his occasionally self-pitying misgivings, an extremely fine poet, worthy of … shall we call it the Cape Town School?

I’d like to end this review by looking at the last poem in the collection, “Kingdom of Rain II”, not only because of the way it contrasts “Kingdom of Rats” but because of the way it speaks back to “Kingdom of Rain” in This Carting Life.

If “Kingdom of Rats” is the poet’s “real” world, “Kingdom of Rain II” is his dream world. The animals are a bit more romantic: bears, tigers, and leopards, and they take us out of South Africa into the world at large. If “Kingdom of Rats” is about “the world’s oldest anger” – man’s inhumanity to man, “Kingdom of Rain II” is about the consolation of nature – the consolation Kelwyn Sole finds in birdsong, that D.H. Lawrence finds in reptiles:

If men were as much men

as lizards are lizards,

they’d be worth looking at.

(“Lizard”)

“To see the whole mechanics of leopard,” is how Kozain puts it, “in its easy possession of what belongs to it”. Yes, it’s the African leopard that the poet settles for, not the western bear or the eastern tiger, and he does it most beautifully in the final lines of this volume:

... I seek no deeper meaning,

no encounter by which to turn this verse

into a dispatch from some other kingdom

or the failed settlements of philosophy.

Yet, I want to let that leopard know

that it is part of me

and I am part of it

in all the ways that that could mean.

Notice the stammer that is not a stammer in the last line! The poem is a dream and this final stanza is, as Keats might have put it, a wish beyond the shadow of a dream. It is conditioned by the words“‘want” and “could”.

Road work, spades, chisels, groundwork: all ways of labelling the poet’s craft – the dialectic of content and form, which in this dark collection, is considerable.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Thanks, John, for sending me back to re-read these fine collections, and for such an elegant, leisurely, intelligent commentary.