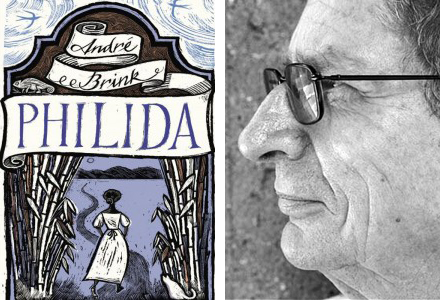

Philida by André Brink. London: Harville & Secker, 2012.

Readers familiar with André Brink’s oeuvre are likely to experience his 24th novel, Philida, with a sense of déjà vu. Familiar scenes, familiar characters and explicit references to some of his previous novels, especially his other “slave novel”, A Chain of Voices, not to mention the perennial theme of freedom, might give readers the impression that they have read all of this before. Despite the familiar ring, however, there are many good reasons why Philida is well worth reading. Some of these reasons must have made an impression on the Booker Prize judges, too, because they included Philida in the Booker long list for 2012.

One good reason to read Philida is to enjoy Brink in full flight as a master of storytelling. Slavery is by no means a cheerful topic and the horrifying truth of it all is exposed in the narrative by keeping a close check on archival research. Such an offering might easily have become a little too harrowing for many readers, but Brink balances the narration with comedy, although the humour is often distinctly dark. In addition, Brink manages to evoke, in his narration, a sense of enchantment and wonder – a combination requiring a special kind of storytelling genius.

As one gets drawn into the world of slavery in the Cape Colony in the 1830s, one also finds oneself confronted with the contemporary world, and with the conventionality of one’s own ideas. Brink inspires one to think creatively, beyond the boundaries of a conformist world. Brink has done this throughout his writing career, and although skeptical readers might find Philida a touch repetitive, there are many people not familiar with Brink’s work who are likely to find this narrative, with its almost magical digressions and many allusions, energetic and invigorating. But even those Brink readers who are inclined to be doubtful (most of them South African critics) should pay due attention to Philida – because it is a well-crafted and thought-provoking novel that offers important new insights, as well as corrective perspectives in relation to some of Brink’s previous novels.

The weighty question of freedom, including the conditions which threaten the human imperative to live freely, have always been central to Brink’s work – whether this is personal freedom (on an existential level) or physical freedom (constrained by repressive political and social structures). As can be expected from a novel drawing on historical research about slavery, the emphasis in Philida falls squarely on questions such as these.

Philida is a slave on the farm Zandvliet. Back in the 1830s, the farm was owned by Cornelis Brink and, according to the “acknowledgements” at the end of the novel, Cornelis Brink was a brother of one of André Brink’s direct ancestors. According to the archives, Cornelis Brink’s son, Frans, had an intimate relationship, over a long period, with Philida, spawning four children with her. Brink’s story takes its point of departure from the recorded incident of Philida laying a complaint against Frans Brink. The somewhat more lenient slave laws introduced under British rule made it possible for Philida to lodge such a complaint. This she did when it became clear that Cornelis wanted his son to marry the daughter of a notable family from the Cape, and Frans refused to buy Philida her freedom in order to marry her, as he had promised.

Cornelis Brink himself is an illegitimate child of a slave woman who was raised in his father’s house. This often happened in the old Cape but was mostly kept out of the history books, especially during the era of rising, and then ascendant, Afrikaner nationalism. Cornelis wanted his son to marry Maria Berrangé for two reasons: so that his descendants would be “white”, and for the economic lifeline this marriage would offer his struggling farm.

As in A Chain of Voices, On the Contrary and Praying Mantis, Brink makes extensive use of historical research. In A Chain of Voices the emphasis falls on a slave revolt in the Bokkeveld in the 1820s, when rumours about the abolition of slavery were mounting. In Philida the Bokkeveld revolt is part of the general picture, but the focus moves, temporally, to a few years later, from 1832 until the final abolition of slavery in 1835.

Another similarity between Philida and A Chain of Voices lies in the way Brink uses several narrators. The novel is divided into three parts. In the first part Philida, Frans, Cornelis and Ouma Nella take turns to recount their versions of key incidents on the farm. On the one hand, such use of multiple narrators consistently surprises the reader with new information, but it also helps to create a certain degree of empathy with the slave owners, for whom it is difficult to feel much in the way of compassion. In the second part, an external narrator describes Philida’s experiences in Worcester until the abolition of slavery. In the third and final part Philida gets to have the last word as she recounts her journey to the Gariep.

The slaves are given voice in a kind of pidgin or creolised English, suggesting the slaves’ use of a bastardised Dutch – early Afrikaans, in fact. This peculiar use of english (certainly not ‘English’) reminds one of Henry Louis Gates’s argument in The Signifying Monkey (1989) that colonised people and slaves often have no recourse to resistance other than linguistic improvisation. Such play with the oppressor’s language is a way of avoiding the rigidity and despotic rules associated with oppressive structures and systems. It allows for ambiguous meanings and potentially opens up creatively new and different ways of narrating. (In the Afrikaans version of the novel, a colourful and often crude Afrikaans is used by the slaves.)

As one can expect from Brink, Philida is also a story about love, sex and betrayal. The relationship between Philida and Frans is narrated with a great deal of tenderness, but their unequal social standing makes this a love that Frans finds impossible to carry through. He promises to set her and their children free, but when he finally needs to translate words into action, he backs off. He simply doesn’t have the courage to resist his father’s – and his society’s – norms, which are part and parcel of their attempts to “preserve” the white race.

Frans lacks the imagination to conceive differently of the world. This, precisely, is the difference between Frans and Philida. She questions the status quo, she can imaginatively narrate her own story in several different ways, and such creativity, paralleled in the novel with her ability to knit, is ultimately the difference between slavery and freedom.

Philida, like her predecessor in Praying Mantis, Cupido Cockroach, is obsessed with writing. She wants her name to be entered in the family Bible alongside that of Frans. But he counters that this is impossible because only white names may be written in there:

The more I told her it was a book for white people only, the more she kept on: It’s

just a lot of names, Frans, it says nothing of white people and slaves.

Philida, it doesn’t work like that, there’s nothing you or I can change

about it, this is just the way the world is.

Then we got to change the way of the world, Frans, she goes on nagging,

otherwise it will always stay the same.

No, I keep telling her, some things just cannot be changed from the way

the LordGod made them.

Then we got to start changing the LordGod, she says.

You don’t know that man, I warn her. He’s a real bastard when it comes to

making trouble.

I tell you that I want to be in that Book, she goes on.

I’m telling you, Philida, I keep insisting, it can’t be done and it won’t be done, and that’s the way it is.

Then give the pen to me, she says in a temper one morning, when all the

house people are busy outside, it is only her and me in the voorhuis. If you can’t

or won’t do it, I’ll do it myself. And she grabs the pen out of my hand (37-38).

Protagonists who refuse to accept the way the world is structured, are a constant feature of Brink’s novels. His protagonists invariably want to change the world, often against overwhelming odds – Josef in Looking on Darkness, an ordinary teacher in A Dry White Season, Estienne Barbier in On the Contrary, Christine in Imaginings of Sand, Cupido Cockroach in Praying Mantis, and Hanna X in The Other Side of Silence, among others. Often these characters do not live to see the changes for which they so gallantly fight.

Galant’s ambition to rid the world of slavery in A Chain of Voices ends with his own death. But Philida visits some of the imprisoned and disillusioned slaves who took part in Galant’s rebellion. She feels it is important to tell them that their deed, although apparently futile and life-destroying, still inspires hope in others.

The will to say “on the contrary”, to say “no” to the way the world appears to operate, requires strong and deep imagination. Brink’s novels have always evinced a marked emphasis on the role of creative imagination as a cornerstone of resistance, and in Brink’s essays, too (notably in Reinventing a Continent), the power of imagination is a recurring theme. Creative imagination is closely associated with the art of narrating, with stories. Many of the important characters in his novels are storytellers: Ma-Roos in A Chain of Voices, Cupido Cockroach’s mother in Praying Mantis, Ouma Christine in Imaginings of Sand. Stories often have healing powers, for instance in The Other Side of Silence. In On the Contrary, Rosette (another slave woman) tells Estienne Barbier the story of a creation myth in which the world was narrated into being by a female storyteller. Scheherazade’s ability to avoid death by telling stories is often evoked.

Philida, too, realises that words are powerful, especially in the form of stories. Her task as a slave is to knit, and knitting becomes a metaphor for telling stories:

At first it’s just wool, but then it change between your fingers and turn into something that can keep you warm in winter. It’s like when you talking and you take a lot of words and put them together like loose stitches on a needle, and suddenly you find you saying something that wasn’t there before. It’s some sort of magic that happen in your mouth, just like between your fingers … You can say cat, or you can say dog, and then you can make the cat sit down or catch a butterfly, or you can make the dog bite and then stop biting, whatever. And you can say: Look, there’s a butterfly, and suddenly the butterfly is there, even if there is no butterfly you can see anywhere. You just make it there.… Or when the Ounooi is giving you hell, you can say, There’s a tick, and then you can make that tick bite her just where and how and when you want to, and she won’t even know why you laughing. She only itch. (98)

When she is initially shown how to knit, Philida simply continues knitting, making a long thin rope. Ouma Nella warns her in jest that if she knits like that, it could later be used as a rope with which to hang her. But Philida discovers different patterns and later experiments with various combinations of patterns and colours. Her abilities are not appreciated by her owner, who punishes her for her improvisation. (“A slave is there to work, not to think.”) The implications are clear: if one simply continues to knit in the single way one has learnt, it becomes a long rope that might lead one to the gallows. But imaginative improvisation, finding new ways of stitching words together, although dangerous, might yet lead to freedom.

The slave-owners Cornelis and Frans both lack this kind of imagination, this ability to improvise and tell new stories. Frans cannot imagine a world that differs from the one that, according to him, was created by the “LordGod” exactly as it currently is. Although it is emphasised that he is physically stronger than his father, he doesn’t resist Cornelis. After betraying Philida, he contemplates suicide, but he is too much of a coward to follow through on his intentions. He cannot conceive of a world in which he and Philida can live together. The material needs of the Brinks, and the necessity of his marriage to Maria Berrangé as Zandvliet’s saving grace, cannot but override his love for Philida. His pathetic attempt to explain this to her and to retain her favour by giving her a gift does not come off at all – Philida sees that his basic premise will remain one in which there will always be slaves on the one side, and bosses on the other.

Cornelis Brink comes close to realising his own inability to think beyond the abolition of slavery. Although his own mother was a slave, and despite acknowledging this fact in public at a slave auction in Worcester, he is unable to create a worldview that can accommodate such a reality. He admits to himself that his own worldview is inadequate, but he sticks to it nevertheless with the resolute will of a tragic hero.

Cornelis has a typical Old Testament sense of the world and he reads only Bible passages from the Old Testament. He believes in a “LordGod” who has placed him on his farm with a purpose. In this way André Brink links up, too, with the tradition of the Afrikaans plaasroman in which the farm is seen as a god-given home and the farmer has a responsibility to preserve such hallowed ground at all costs. Unity with the soil has strong metaphorical significance. Cornelis realises that his claims to the farm are not that strong. He stands in the graveyard on the farm and notes with regret that that there are no Brinks buried there: they are new to this farm. Then Petronella reminds him that there are uncountable others who have lived on the same farm, before them. In spite of this, though, and in spite of his mother having been a slave, he prides himself in the way the white population is growing – even though many of them are of mixed origin. For him the ways in which this past is recorded are more important than the truth:

One day in the future, when none of us is still around, that is all the world will know, and all that needs to be known. We came to this land white, and white we shall be on the Day of Judgement, so help me God. If anybody is still in doubt, I always tell them: Just follow the coast up to the Sandveld, then you will see with your own eyes how we whored the whole West Coast white. God put us here for a purpose, and we keep very strictly to his Word. For ever and bloody ever, amen. Do we understand each other? (74-5)

Cornelis has a growing sense of uncertainty about his god-given place as baas. When he thinks about the way times are changing, he realises he has reached a dead-end:

The only thing we still have to cling to, is God. But he has also started to falter… All that will remain for us to trust, I think, is the land itself. And it is bound to find its own way of punishing us. Don’t make a mistake. Ever since we arrived here everything has begun to go wrong. Perhaps it would have been better for us never to have been here. But if I no longer have that to believe in, what remains?” (95)

Cornelis lacks the imagination to think about a different future and he continues to “knit a rope”. Like many tragic figures, he is blinded by his inability to imagine new possibilities for living and so he uses all the power at his disposal, acting in the most despicable manner, to force the changing world to stay in line with his unchanging views.

Brink does not completely romanticise the notion of trust in creative storytelling as a path to freedom, as Philida also feels compelled to acknowledge: "What happen to me will always be what others want to happen. I am a piece of knitting that is knitted by somebody else."

But real freedom requires the ability to imagine another world, to imagine another origin, and to imagine a different future. Philida can discover what freedom really means only after a long journey to the Gariep River. The Gariep, where runaway slaves, escaped convicts and many others live as free people, becomes a symbol of freedom. Through allusions to T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”, this mythological Gariep becomes the “the longest river”, going back all the way to paradise via the “unknown, unremembered gate”:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

Brink invokes these immemorial lines by Eliot in order to think about freedom as the ultimate prize for human exploration. Philida realises that her freedom is not to be found at the Gariep or any other specific location. Freedom is within herself. After travelling all the way to the Gariep, she arrives where she began, but now, for the first time, she recognises her freedom.

Brink’s novel becomes more than a harrowing picture of slavery in the Cape Colony. It becomes more than an exploration of the roots of inequality in South African society. It does more than uncover prejudices. It becomes an exploration of the very idea of freedom. But this is not a freedom in the obvious sense of freedom from racial prejudice or a never-ending class struggle; it is freedom on an existential level, too, for anyone and everyone.

At one stage, Cornelis Brink reflects on the problem of selling a slave at a time when it is clear that slavery is about to be abolished. He worries about the prices he is getting for his wine and rising production costs. He worries about the Brinks’ reputation. When his wife tells him not to worry so much, he responds: “I must worry, I’m a Brink. If I don’t worry, what will happen to the world?” (126).

André Brink is also a Brink. And he also worries. He has always been worried about the South African situation, about inequality under apartheid and now still, about the country and its future. By telling the stories of slaves who have not been heard sufficiently, Brink offers a counter-discourse to “whitewashed” versions of history. On these journeys to the past he leads readers into a fuller recognition of the present, and encourages them to imagine a different future.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project