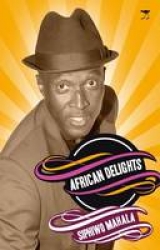

African Delights by Siphiwo Mahala, Jacana, 2011.

In 1963, Can Themba published a short story called “The Suit”. It is about Philemon, an earnest and thoughtful young husband who lives with his wife Mathilda in pre-ruin Sophiatown. Devoted and doting, he provides his wife with breakfast in bed and performs all the household chores before leaving for work. Philemon eventually discovers that Mathilda has a lover who visits her every morning after he has left for work. He rushes back home (there are resonances of Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata) and discovers his wife in bed with the man. The man flees, leaving his suit behind. Philemon has a kind of awakening – a revelation of what the world truly means. He never mentions the adultery. Instead, he insists that Mathilda treat the suit that remains behind as a guest. The charade goes to agonising, disturbing lengths, and Mathilda eventually commits suicide. When Philemon realises that his actions have driven her to kill herself, he cries out in “screwish anguish” for her. The story ends on this moment of illumination.

This story is the on-ramp from which Siphiwo Mahala chooses to merge with South Africa’s literature. His new work, African Delights is a collection of some twelve short stories, grouped into pairs of three sections.

The first section will undoubtedly garner the most attention. Titled “The Suit Stories – a Tribute to Can Themba”, it begins with a writing-back, jeu d’esprit, to Themba’s original story. “The Suit Continued” is a reimagining from the viewpoint of the suit’s owner. More than just a portrait of Sophiatown life, the story is striking in the particularity of its perception of the original story. It goes to the heart of Themba’s narrative and draws out select details, mixing the fictional with the real such that Can Themba himself becomes a character in the same virtual space as Philemon.

The first section will undoubtedly garner the most attention. Titled “The Suit Stories – a Tribute to Can Themba”, it begins with a writing-back, jeu d’esprit, to Themba’s original story. “The Suit Continued” is a reimagining from the viewpoint of the suit’s owner. More than just a portrait of Sophiatown life, the story is striking in the particularity of its perception of the original story. It goes to the heart of Themba’s narrative and draws out select details, mixing the fictional with the real such that Can Themba himself becomes a character in the same virtual space as Philemon.

The conceit only occasionally bottoms out, striking a slightly clumsy note in places where the suit’s owner injects his narrative with historical details. The following is just such a place:

you see, journalists like Can and Henry were real trouble in those days. They were willing to risk their lives in pursuit of a scoop. Actually, that’s how Henry died (bless his soul). I particularly liked Henry because he was dedicated to fighting the injustices. As Mr Drum, Henry exposed the brutal treatment farm workers got (18-19).

The author is playing his hand here too obviously, as if guiltily aware that he is straying too far from the original. But on the whole, Mahala has an extraordinary mind for mapping the comic ugliness of the ghetto, and the prose takes on the stride of a voice, rather than an effect. He might be accused of merely being a good copyist when he ladles the already extant flavours of Sophiatown into his story: exposure to the historical archives and DRUM, abundant to overspilling with the rhythm of the township, threatens to turn all of us into critical scholars of Sophiatown. But Mahala’s writing surges powerfully past the referential, when a character’s words are not shorthand for an entire cultural space, but an intensely complex, personal and finely-textured gallimaufry.

In a surprising moment of literary hospitality, Zukiswa Wanner, Mahala’s fellow Brat-pack writer, makes an appearance as the author of the second “Suit” story, in which the hapless Mathilda gives her account of events. The act of creating a life for the character is an elegant riposte to the swaggering misogyny Mahala and other writers of his ilk too often call on. The stories cross one another’s paths, fleetingly, teasingly, setting up an intimate reading-relationship that is tailed perfectly by Mahala’s “The Lost Suit”. The trio moves in the shadow of Can Themba’s original, but it is no poorer for that.

The trio of “Suit” stories that begin this collection will undoubtedly receive the most attention. But that is not to detract from the other sections: “White Encounters” is particularly well-rendered. Mahala writes in profoundly spectatorial gradations of the paradox-filled experience of encountering white people. The author states that he drew on memories of his childhood growing up in the township Joza during the eighties, and it is this experience that informs the first story and permeates the other two, even as they access different, later, historical moments. Skirting the colonially-styled “frontier city” of Grahamstown, Joza’s location (and its status as an Apartheid Location) provides a suitably pitched imaginative space for perceiving this encounter. Here, Mahala does not succumb to the temptation to providing tele-visual dialogue to enhance our sense of what the character is experiencing. Instead:

It was hot but we walked under the shade of trees that hugged the road. Cars whizzed past. We went past tall buildings that looked like they were going to fall on us. We saw white people’s children holding bags full of books . . . some waved at us. We crawled up the hill. The 1820 Settler’s Monument gazed at us from the top of a hill on the opposite side of town. The structure looked like a ship that had been dropped from the sky. I was getting tired (65).

The prose is subdued yet evocative, and its firm declarative sentences keep us tethered to the child’s point of view as they walk up the hilly streets of Grahamstown, nomads amidst a leafy, hilly tranquillity in which they cannot tarry too long. Mahala writes the unmomentous, unobserved moments of daily Black life into being, tapping the pulse of the undramatic life as capably as Ndjabulo Ndebele did in Fools and Other Stories. His writing in this story particularly has a certain power that prompts the reader to notice the hitherto-neglected.

Another story that stands out is “Hunger”. Mahala goads the narrative into releasing sounds, smells, steaming bodily sensations. The language trembles on the precipice of being something Philip Roth would write, for Roth is similarly enamoured of the body in all its noisy physicality. If Mahala doesn’t quite have the ear for tuning the timbre of the body, then he comes admirably close.

The third section of this collection, “Truth” is an exit strategy from the dictates of truth. As Mahala says, “Truth is forever elusive”, and the three stories that comprise “Truth” are located at various points of rupture, Mahala diving down off-ramps on truth’s too-straight axis to more liberated spaces where facts can be remixed. An awkward moment where he is called forward to speak for the honesty of his earlier novel becomes the performative space for the ambiguities of fiction-writing.

Of the last section, the eponymously-named “African Delights”, let it suffice to say that the author’s knack for glancing portraiture of Black urban life does not falter. The stories are uneven, cobbled tales where the social and economic mobility of life for middle-class Black citizens is bisected by petty jealousy, infidelity, and the various other complications that define life in the contemporary moment. The reader is drawn into various rooms where characters play out banal domesticities in the era of tenderpreneurs and economic inequality. To read these vignettes is to feel in the presence of individuals: men and women differentiated by mood and richly coloured in by the writer’s words.

The cover of this collection carries a blurb from Mandla Langa, and while it is easy to dismiss such copywriting as so much puff, I would certainly agree that African Delights constitutes “a timely intervention in our literary life.” It is not unduly high praise, for the work is an unaffected and honest achievement. Mahala’s work is a new entrant to a field where much that is termed literary clusters around questions of seeing and being seen and rendering visible, and his stories form an unexpectedly prescient prism through which society lurches into focus.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project