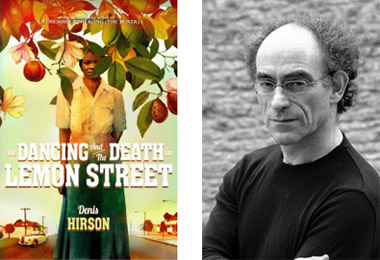

The Dancing and the Death on Lemon Street by Denis Hirson, Jacana, 2012.

There was a substantial gap between Denis Hirson’s first book, The House next Door to Africa (1987) and his second, the Joe Brainard / Georges Perec-inspired I Remember King Kong (the Boxer), which appeared in 2004. Following this, Hirson has published prolifically: more work in the “I Remember” format, poetry, a history of South African literature, and now a novel. The unusually helpful epigraph – alerting us to how the novel works – reads: “Place a red bookmark at the opening page of the book, for in the beginning the wound is invisible.”

The story begins in 1960, in a northern Johannesburg suburb, green (there’s a park), if somewhat run-down, the street a “deceptive slope of tranquility.” There are few cars, no swimming-pools (o tempora, o mores). There’s a regular fah-fee man, and there are maids and nannies (his inveterate customers). In that quiet, deft way he has, Hirson introduces – vide the epigraph – quivers of apprehension: “Given the rigour of [the maids’] work, it seemed as if they had been ordered not simply to keep the place clean, but remove some constantly reappearing, unnamed yet ubiquitous form of intrusion, of which dirt was merely the most superficial sign.”

The characters are introduced in a cluster: Mr Van Aarden, who has a pondokkie-like house, and is viewed with suspicion by his neighbours, though no-one can quite put a finger on the reason for this; young Jonathan Miller and the Reynolds family. There’s some agreeable, quirky humour, in the neighbours’ hazarded guesses – for Jonathan’s benefit – as to the meaning of Lemon Street’s designation as a cul-de-sac. From the outset, the third person narration is elastic, allowing for shifting focalisation, so that a character’s way of looking at things will seep into the telling without taking it over: “She herself never touched the stuff, one drinker in the house had been quite enough thank you very much.”

Then comes the arresting opening to the plot: “At this time there was a death on the street, the only violent death in living memory. One person in particular would have known with instant certainty that it was more than half intended as a murder. [What skillful calibration of terms is here]. And yet this same person, who lived on the street, was strangely unaware that a death had taken place at all.”

Race consciousness is touched on early in the narrative, with a white character’s “overheard” reflection that: “Natives never know what to do next, remember nothing and are bone idle.” From the opposing point of view, a domestic helper at work exists “in a place where she kept her eyes down, her pride and person taped back behind the apron and matching doek of humility”. When her employer, Felicity, berates her: “Still the words came stinging at her, a toxic swarm of them, as if she were nothing but a colour, a smell, the waste of an animal, where did this woman find such words that only a drunk man would think of using, surely only a drunk man could draw such words out of the stinking vinegar of his body?”

Aware that I am quoting at length – but Hirson’s writing is irresistible – there follows an account of the nightmares of Felicity’s late husband, back from service with the Eighth Army: “There were fragments of sentences bits of conversation with someone, a constant, strangely high-pitched note of fear, cracked as lightning, illuminating for an instant an entire landscape of sand and tanks, exploding shells and fleeing men: Chappie had brought the war back to his own bed. While he might appear to be lying next to [Felicity] restlessly in a glaze of sweat, he was in fact not even in the same country as she was.” This is a fine example of how gracefully Hirson can write, but with such heft.

Felicity carries a disquieting memory: of passing two exceptionally debonair and undeferential black men in the street, and seeing them entering the Miller property, followed by a burst of group laughter. Another character wonders, is it true, as her husband claims, that the Millers are communists?

Half-way through the novel comes the dance and a confrontation between young Jonathan Miller’s father and the hostess, with him accusing her of not having the faintest idea or concern as to what is going on in the country and challenging her to “take a step into any township, or slum yard, or mine compound”. Then he attempts to seduce her, and the aftermath of this brings the book’s bubbling, subterranean apprehensions to the surface.

After this Hirson starts bringing narrative strands together more tightly than before: the back story of the domestic helper Rosy, especially her repeated abuse by men; Jonathan Miller’s tense but loving relationship with his father – the latter always kissing him before he absents himself (on what clandestine mission?); passages from Jonathan’s novel of the moment, Wells’s The Invisible Man (especially the shooting of the central character); and Felicity’s continuing near-obsession with the inscrutable Mr Van Aarden. Tension is heightened with the section-opener “Mid-morning on Lemon Street, just a couple of days before the news broke”. By now it’s clear that debut novelist Hirson is as expert with plot as a seasoned thriller writer such as Kate Atkinson.

The big news, when it comes, is of overwhelming import: Sharpeville. Yet the residents of Lemon Street continue to discuss Princess Margaret’s forthcoming marriage – though one notes the newspaper headline “PASS LAWS NOT BEHIND RIOTS; VERWOERD” and asks herself “Not, not, well then what, what?” Each house is like a crucible, one maid aghast at the photos of the massacre, men laying dying, but transformed by whatever horror they can see to their left, while next door a white boy whinges that his maid hasn’t prepared his tennis clobber.

Jonathan’s father is arrested while attempting to reach the border, and the house searched for incriminating publications. Hirson’s metaphor for the impact on Jonathan is characteristically eloquent: “Nothing left at all but the vacuum in the house, through which the world sank like a rock hurled into water, trailing only a few lost beads of air, not enough to breathe.” A newspaper announces a grim new piece of legislation (one this reviewer had never heard of before): “If somebody is arrested his family may not tell anybody and neither they nor the neighbours may spread the news. If they do they become liable to a fine of 500 pounds or five years’ imprisonment.” There follows a sharply moving scene between Jonathan and his mother, which reminds one that Hirson knows all of this from his personal experience.

The death signaled in the title comes towards the novel’s end and, though horrible, is also sardonically comic (faintly reminiscent of a famous episode in Our Man in Havana): at the same time it speaks to the complex psycho-social morass, the grinding injustice, that the book has so consistently and powerfully unveiled.

More Denis Hirson on SLiPnet:

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project