LUKE BUCHANAN

It’s a mild Tuesday afternoon in Cape Town. I pick my sister up in Mowbray, en route to the Fugard Theatre on the outskirts of the CBD, where Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act is being performed. Of course, I say it’s "on the outskirts" of the CBD, this is how I would place it on a map, when in truth the Fugard Theatre lies in the centre of what used to be District Six, the once colourful “Coloured” capital of Cape Town.

Named after none other than Athol Fugard, revered as one of the world’s greatest living playwrights, the 280-seater Fugard Theatre is to be found within the historic Sacks Futeran building, with the renovated Congregational Church Hall in Caledon Street as its entrance. Built as “a crucible of creativity and beacon of humanity for all South Africans regardless of race, colour, gender or creed”, the Fugard honours the man who, along with John Kani, Winston Ntshona, Zakes Mokae and others, helped to pioneer the genre of protest theatre in apartheid South Africa.

With his ability to capture the sweet little moments through the lens of a broader, more insidious context, Fugard's plays captured the spirit of the oppressed masses, and the tortured outsider-insiders within a grinding political machine, fuelling political awareness at a time when government censorship and black consciousness were vying for the upper hand. Censorship claimed many victims, but in the long run, the spirit of political protest won the war against a blind, blinding censorship that now looks like no more than the ugly death-drive it always was, anyway.

Statements, first written in 1972, hasn’t been professionally performed in South Africa for 40 years. This raises the question of its "relevance" in the current context, which is a touchy subject when it comes to work as revered as Fugard's plays. Interested in discovering what sort of audience this play would appeal to nowadays, I make my way into Caledon Street. I am guided to a parking spot by a securi-vest individual. Nearby, the Harley Davidson Club of Cape Town roars with the gruff laughter of hairy bikers. The cheerful walls of Charly’s Bakery are studded with anthropomorphic chocolates and pastries. Surely this can’t once have been District Six? Surely this place bears no relation to Richard Rive and his merry band of pranksters? Now more than ever Rive’s work seems abstract, more fictional than factual. Little physical trace remains.

The Fugard Theatre sports gothic windows, tall wooden doors and laminated wood flooring. Plasma screens mounted on distressed brick walls flash images of upcoming plays and productions. An odd combination of a classic theatre auditorium and an upmarket cinema nouveau. However, the absence of popcorn and the niggling presence of ushers remind you that you've paid R140 to watch real theatre, not George Clooney's face flashing at you at 24 frames per second.

The Immorality Act, signed into law in the 1920s, updated in the 1950s and scrapped in 1985, forbade interracial canoodling. Does the play mean anything now that the legal constraint has gone? Does the play mean more than its howl of protest – does it "transcend" its context, as the literature lecturers sometimes say about "great" works of literature?

“Please be warned that a strobe light will be used in the play”, signs on the outside of the theatre read. Seems we’re in for some excitement. Taking my seat, I’m flanked on either side by ageing whites – couples, friends, family. I reflect that it’s a sad to see live theatre largely attended by the coffin-dodger variety of person – the youth, it seems, wants to be entertained by strobe lights, not warned about them.

Thanks to the artful direction of Kim Kerfoot, the play still packs a punch. It may be a vague punch, aimed at an absent enemy, but it’s still there. Kerfoot directs Bo Petersen (a white woman) Malefane Moshuli (her lover, a person of colour) and Jeroen Kranenburg (a policeman) in classic Fugard style, punctuating poetic monologues with short, often comedic quips, two-stepping between the archly theatrical and the brutally realistic.

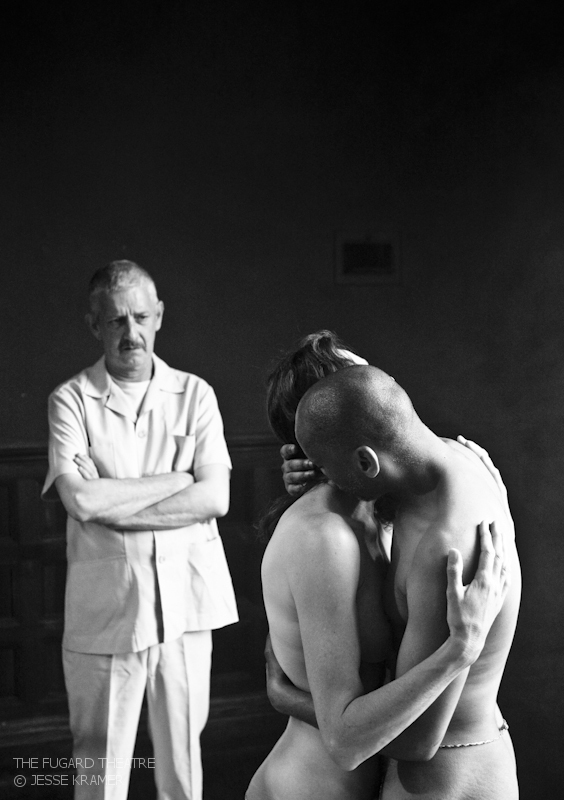

The lights come up on the interracial couple wrapped in a blanket on the floor. Coupled in a sweet embrace, gritty naturalism comes to the fore as they emerge from their makeshift woollen nest, naked as children. Their nudity, together with their frank and easy conversation, creates a sense of serene honesty, which is paradoxically juxtaposed against the deep dishonesty of the political context in which they find themselves. They stand bare and vulnerable – and proud – in front of the audience, or jury if you will. The omniscient judge, die polisie, die meester, sits in a darkened corner of the stage, watching but not seeing.

The play still delivers body blows, such as when Malefane refuses to accept water from Petersen. Although his township has run dry, he admits he cannot accept her offering. Not because of pride, but shame: “I feel like a brak, skulking in the shadows on the way back from town.” He’s relinquished enough of himself in conducting this clandestine relationship, internalising the “wrongness” of it through fear and trembling; carrying water like a beggar from town into the dry township would surely destroy what is left of him. This is a reminder that the geographical imprint still remains in the post-apartheid milieu, the braks and the shacks and the town centres, and the distance in-between.

My father (he saw the likes of Yvonne Bryceland, Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona in Fugard plays like Orestes and The Island at the old Market Theatre in Johannesburg in the 1980s), says to me after the play, over coffee: look, dude, the real point of this Fugard play is the quality of doomed love in it, not so much the "protest". Apparently, the love is the only reason the protest had any point in the first place. He thinks the love outlives the conditions behind the protest, just like Fugard himself always said it would. Persistently, throughout his career, Fugard disputed being a "political" writer. Fugard knew, my father argues, that apartheid would end, and that literature would not, and so he opted to go big, for literature. He reminds me that Fugard opted to immigrate to the US purely because his "allegories of failing love" were seen more widely for what they were in the US, by more people, and against a bigger human backdrop. South Africa and its politics became a too small for Fugard, although he would never "leave" the country in his writing. His art remains rooted here.

Watching this play, I remember from my lectures that protest theatre is grounded in a gritty kind of street realism within the mould of Grotowskian “poor” theatre. Statements also makes sudden and remarkable jumps from naturalism to the avant-garde. After the initial dialogue, the stage darkens, and a sickly green light from below the police officer’s desk at the back of the stage throws his shadow up massively against the wall. He calmly lights a cigarette. As he delivers the immorality charges, the contrast between the real and the spectral becomes clear: the nude reality of an illegal but pure love (presented "realistically") is contrasted with the demonic, the unquestionable terror of a judgment that is about to be invoked upon the lovers. This grim judgment (presented "surrealistically"), intrudes and suspends the intimacy of this bare, "natural" scene. This intrusion is indubitably relevant, undeniably shocking. Or at least it would have been, had I been watching this as a youth in ’72. But I wasn’t, and I’m not.

This other dimension of terror, this spectral, psychic invocation of a Law of the Father, here internalised in the form of fear and externalised as a policed, raced society at odds with its own need for love, invades the naked realm of things, when police officers barge into the lovers’ secret rendezvous and take violently flashing snapshots of the two of them. Here is where the strobe light comes in, shuttering the two victims – the bare lovers – viciously in jaws of white light as the stricken duo lurch about, terror-struck. The invasion is poetically, surreally, brilliantly enacted. The whole thing is undeniably moving. In fact, it’s shocking and terrifying. But I’m left asking myself, to what end? Perhaps that’s what’s missing, the end to which one is supposed to be moved, the action one is supposed to consider taking.

But my father says to me, later: No, forget about taking action. The play, performed now, tells you this: 1) Fugard was right – the solidarity of human love is always going to outlast sectarian political motivations; 2) The story of failed and failing love under Apartheid is a window into the bad shit that went down in the past, sharply warning us about the unhealed racial hurt still out there, now. 3) Fugard’s Statements remains a play of great power, especially in how it shows up the "representing medium" of photographs as a kind of violent trap. It traps the lovers inside black-and-white frames, frozen forever in their ugly fate. This, he says, is a uniquely 20th-century moment, modernity in crisis, modernity eating itself up. Fugard’s Statements remains an "allegory" of ordinary humanity’s necessary struggle against persistent forms of structural imposition. In the new century, evidence of this is to be found in the Occupy Movement, but the stage is much bigger, much more systemic – no longer isolated within "bad" nation-states like the old SA. Now it’s big, it's Neo-Liberal, it’s a world problem, the impositions are eating up the planet …

The play ends, the cast bow, the audience stand up like museum visitors, applauding this most beautiful relic of a bygone era. Yes, I’m moved. Fugard’s hauntingly honest, gritty, human style never fails. His play still packs a punch, it creates a dance of shadows in the air. His writing still moves us, but I’m still not entirely convinced to what end.

For me, protest plays occupy an odd place in post-apartheid theatre. Where they once dealt decisive blows to the culture of apartheid, where they once lit the fuse to the conflagration of black consciousness, they now seem to occupy a space in a glass box, with a bronze plaque underneath. An artefact. Something has been lost. I think my father might be confusing nostalgia – a memory-infused sense of "relevance" about heroic protest in the bad old days – with continuing significance. Like an aged boxer who’s hung up his gloves, protest plays now stand outside the ropes, offering advice to the next generation of fighter. While the doughty old fighter has all the knowledge of an established boxer, his fitness has waned, and the youngsters with whom he used to violently thrash about in the ring now occupy middle-class homes, drinking tea and watching Generations. He has no one to punch anymore.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project