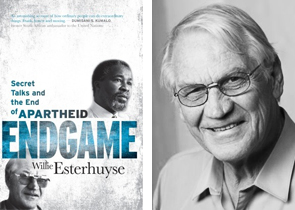

Launch of Endgame by Willie Esterhuyse, 3 July 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town

KAVISH CHETTY

In a long, nostalgic anecdote Willie Esterhuyse recalls his encounter with Lee Blessing’s 1988 play, “A Walk in the Woods”. Its resonance to his affairs at the time is immediate. The play deals with the complex, embattled relationship between two arms limitation negotiators. Esterhuyse’s new book performs a similar function – it sweeps down into the personal relationships and conversations which marked the clandestine negotiations to formally end Apartheid, giving flesh to what exists in the South African imagination largely in the abstract. It was from Blessing’s play that Esterhuyse found conviction in the maxim that “it is possible for individuals to make a difference”. His implicated role in those talks aim to give the work both an autobiographical and memoir-ish personality, but also offer a more intimate perspective of this country’s political history.

Tonight he speaks with journalist Henry Jeffreys, who says the book is “about negotiation and the process of negotiation” and that “the theme of trust runs throughout” the work. Confirming the theatricality that Esterhuyse’s experiences share with Blessing’s play, he notes that a movie was made of Endgame with William Hurt playing Esterhuyse, but cautions that “if you saw the movie, I would suggest that you quickly forget about it”. Esterhuyse composes himself comfortably with his grandfatherly charisma, saying “I am from the Karoo and I can only speak English after I’ve had two or three scotch whiskies… there’s no whiskey here, so you’ll have to try and understand what I’m saying.” He’s being modest, of course – he is a superb raconteur, with a patient and shambling gait to his stories.

Jeffreys’ first question concerns why Esterhuyse chose to write the book. “Were there so many misunderstandings about what transpired in the lead up to the negotiations?” he asks. Esterhuyse replies that he is a compulsive note-taker and discovered large volumes of notes he had scribbled during the talks, neatly filed away. He also discovered notes that he had received from the National Intelligence Agency. “I would receive the notes and questions with the instruction that I should destroy [them] within an hour or two, so I had to memorise them. Now, I can’t remember things. So, I forgot about those instructions. When I saw these files I saw that this was the story of my life and my family.” This was the first and important reason for his decision to write, but a second concerns his relationship with the Mbekis. “I had to write about him because he was one of the architects of the first phase of the process – Mr. Mandela was also, but he was in jail. I realised [the prominence of] the role he played during the ’80s to get the ANC away from the idea that a military takeover of power was just around the corner.” Jeffreys sees in this account, if not corrective then certainly re-texturing, a story of “unsung heroes”.

From here the talk ranges across the dynamics of the negotiation process: fractured confidences, risks and anxieties. Jeffreys expresses interest in the trust issues which would have confronted the process – would the ANC have thought Esterhuyse a “pawn of Apartheid”, and how did he navigate these issues? “Trust and confidence is a bit-by-bit thing,” says Esterhuyse. “I make a distinction between people I trust and friends. I have friends I don’t trust. My argument is that if you begin sharing risk and common objectives and common goals, then it’s much easier to build these bridges of trust.” Over the talk, the two produce a portrait of a restless negotiation process, stemmed and contoured by the possibilities of assassination and subterfuge. “If you make a compromise,” says Esterhuyse, “you must be prepared to take responsibility for the outcomes of that compromise.”

“The second last chapter of the book is about the here and now,” says Jeffreys, and he directs Esterhuyse to the ANC’s idea of a “second transition”. “I have been talking and talking with the hope that time would run out and I would not be asked this question,” jokes Esterhuyse. “Transitions from authoritarian rule to democracy are long processes. One of the reasons why transitions are successful is that you start building institutions that are reliable and effective. Within these institutions, you begin to build the democratic political culture that can take you through the rapids even if some of the individuals are not up to scratch. Another reason is that you contain systemic corruption. The problem with systemic corruption is that you can’t put it in jail because it permeates the system. The post-Polokwane ANC is as far, as I’m concerned, useless at containing corruption.” His emphatic stylisation of “useless” has a well-liquored middle-aged broad sitting behind me clapping her hands and cheerleading – she’s been agitating and completing his sentences with drunken glee throughout the talk, and this is her climactic moment.

But having said this, Esterhuyse does not lapse into the predictable rhythms of cynicism, asking instead “Can I be positive?” He says, “My hope is on what I call the new emerging intelligentsia and professional class, in white and black communities. They buy the book and I get comments from them and have to do all sorts of interesting small group discussions. The big question is not so much about the book – it’s about your question: what now? How can we turn the whole thing around?” Remarking finally on the complexity and messiness of the political process, Esterhuyse says “transition is not for sissies.”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project