Report on Joburg: City of Extremes, with Marie Huchzermeyer, Jonathan Noble and Thiresh Govender.

Session 6, Mail & Guardian Literary Festival, 1 September, Market Theatre.

LARA BUXBAUM

The second session of the day was opened by festival co-director Corina van der Spoel, who declared that any M&G Literary festival is incomplete without a session on Joburg; indeed, it has been a feature of the festival since its inception.

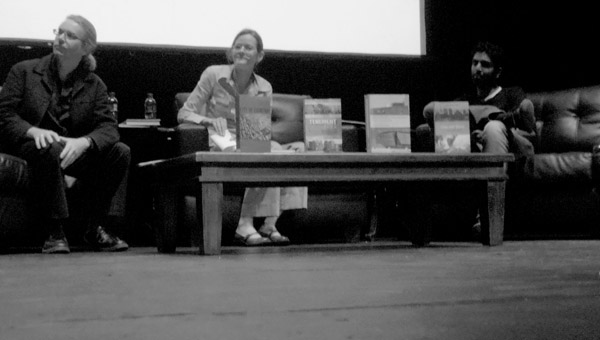

The panel was chaired by Marie Huchzermeyer, a professor at the school of architecture and planning at Wits University. She was joined by fellow Wits academic Jonathan Noble and architect and urban designer Thiresh Govender, who works on projects in Soweto's famed Vilakazi Street and the Constitution Hill complex.

Marie Huchzermeyer, Jonathan Noble and Thiresh Govender prognosticate about Joburg's citiness

Gesturing to the wide array of texts about Joburg displayed on the table, Huchzermeyer pointed to an emerging trend in studies in the city – the titles from the late 1990s and early 2000s suggested a mood of optimism, at the possibilities of “something new emerging”.

More recent texts seemed imbued with caution as they considered the fate of a “city nearing its limits”. Govender interjected enthusiastically – as was his wont throughout the session – that although he didn't have a book of his own to add to the academic collection, he considered the city itself to be “Africa's best read”.

Both Noble and Govender were quick to describe themselves as Joburg enthusiasts, despite their often fraught relationship with this complex and “elusive metropolis”, as Sarah Nuttall and Achlle Mbembe put it.

Wits academic Jonathan Noble points to the endurance of the “prospector mindset” in Joburg, once a wild tent city, a "town of cowboys"

Asked to recount the history of the city, and to identify continuities in its 125 years of existence, Noble pointed to the endurance of the “prospector mindset” that saw Joburg begin as a rough and wild tent city, a “town of cowboys”, once gold was discovered in 1886. Govender identified himself as a contemporary prospector of sorts, who traded a life in Durban and Cape Town for the “spirit” of the city, inspired by the fact that its denizens all seem driven to achieve something. He praised the “ability of Joburgers to interpret beauty at the fringes”, in unexpected places.

If this smacked of romanticism, all three panelists, although prone to poeticise certain aspects of the city, were careful to rein in their enthusiasm with a more sober consideration of the inequalities and exclusions that dog the city. As Huchzermeyer added, even the rebranding of Joburg as an “African world class city for all” (in its latest formulation) implicitly echoes the fact that “world class cities” by global definition are “intentionally exclusionary”.

Jonathan Noble and Marie Huchzermeyer set their sights on Joburg as an imaginary construct

It was a wide-ranging conversation, in which the three shared ideas about the meaning of public space, public architecture and “African architecture”, a Fanonian critique of identity formation in Joburg and Lefebvre's adumbration of the various “rights to the city” that its inhabitants should be able to claim.

It was unanimously agreed that the majority of residents are not able to exercise these three rights – namely the right to participate, to inhabit, and to creatively work in and with the city and to remake it according to one's desires. As Noble insisted, “the right to imagine a city should be for everyone”.

The very idea of the city, which is supposedly the reference point for this conversation, is slippery, as Huchzermeyer asked: “Right to whose city? Whose right to which city?” Or as Govender mused, perhaps we should be speaking of “Joburg's cities”, of how “exciting it is where they overlap”.

Huchzermeyer spoke of her research in informal settlements and the ways in which objects bearing the hallowed brands of this city are re-imagined or recycled for more utilitarian purposes, changing their symbolism.

Thiresh Govender: Johannesburg is only at the start of its “life cycle” - the meaning of Sandton and Monte Casino will ultimately shift

Speaking of cycles and change, Govender proposes that Johannesburg is only at the start of its “life cycle”, that the meaning of Sandton and Monte Casino will ultimately shift. In this sense the very fabric of the city can potentially be recycled by those who engage with it in creative and unanticipated ways.

In considering the future, Noble suggests that what could be termed the tradition of “dirty urbanism” might work best for this city. “Clean urbanism” views the city as “a problem to be solved”; “dirty urbanism” suggests change will be directed from within and is embedded in the lives of those who live in the city.

The most pressing of the questions raised by the audience came from a public arts activist who expressed dismay at the squandered possibility of creating a welcoming public space at the Constitutional Hill complex. The panelists agreed that despite the best intentions, as Noble stated, “the ramparts of [the Old Fort Prison] continue to exclude”, preventing pedestrian throughway. The fate of similar public architecture interventions and the ways in which they interact with their surroundings remains uncertain and a subject for continuing debate, calling for innovation.

In concluding, Huchzermeyer wished that there were a Zapiro figure in the field of urban planning and architecture – to satirise some of the political processes and absurd bureaucracy, but also to enable us to find ways to laugh at our “city of extremes”, and consider it afresh.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project