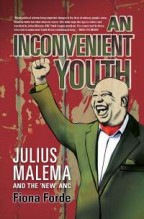

Launch of Fiona Forde’s An Inconvenient Youth: Julius Malema and the ‘New’ ANC, 18 November 2011, Verbatim Bookstore, Stellenbosch.

BY WAMUWI MBAO

If you’ve attended a book launch at Verbatim’s Conference Room before, you’ll know that the venue is rather intimate for a literary event, particularly one of this magnitude. Nevertheless, those assembled for the event are happy to rub shoulders and take up positions on the floor as Forde addresses the crowd, touching on many points she raised the previous day at a similar launch at the Rand Club in Johannesburg. She tells the assembled group that the book is the result of two years work, including two months of closely shadowing Malema.

There are certain postures of conviction that adhere to the position from which one gives an account of Julius Malema. One usually begins by stating that Malema is a controversial populist politician. Then one discusses how Malema alienates white people.

Then one voices rhetorical consternation at the mysterious, intangible nature of Malema’s appeal to some group shadily defined as “the masses”. It is at this point that one situates one’s own work: one arrogates to oneself the role of a mandarin, pontificating on the demise of old certainties and the rise of new uncertainties.

Then one voices rhetorical consternation at the mysterious, intangible nature of Malema’s appeal to some group shadily defined as “the masses”. It is at this point that one situates one’s own work: one arrogates to oneself the role of a mandarin, pontificating on the demise of old certainties and the rise of new uncertainties.

Forde’s discussion is a welcome break from this tendency. The Irish journalist is introduced by Professor Sibs Moodley-Moore, who describes Forde’s book as “rich in insight and perceptive in its analysis”. Moodley-Moore further praises Forde for her meticulous research, which brings nuanced attention to a subject who so rarely receives tempered criticism because he touches on so many emotive issues for this country’s inhabitants. When Moodley-Moore declares that Forde “is in the best position to understand Malema” because of her role as an investigative journalist, she establishes Forde’s expertise, and sets the tone for the rest of the discussion.

With the dramatic outcome of Julius Malema’s disciplinary hearing sending shockwaves across the country, Forde has been in high demand in both the local and international media to render her verdict on the events. She admits to her Stellenbosch audience that she hadn’t expected Malema’s suspension, and that her book should be viewed with that in mind. However, in Forde’s view, “we haven’t seen the end of Malema”. She suggests that “Mangaung [the ANC’s elective conference, to be held in 2012] will be the site of a new battle” for control of the ANC and the state.

Forde proposes that with the Hawks and SARS circling above, things might be taking a nasty turn for Malema, but that she “can’t see him in prison overalls”. With the air of a writer very at home with her subject, Forde frames her discussion in terms of both Malema’s effect on the country and how Malema’s rise to prominence epitomises “a lot of socio-economic problems” that have arisen in South Africa during the past fifteen years. She lingers over the wider implications of the Malema phenomenon, encouraging her audience to view it within a wider picture of the “leadership vacuum” in today’s ANC.

Forde is an accomplished presenter, and she has the crowd nodding along in tranquilised agreement as she pronounces on the thematic concerns of her work. You gain the sense from listening to her that she has a degree of sympathy for Malema, but one which doesn’t cloud her understanding of the danger his brand of radicalism poses for the ANC.

She very deliberately positions herself as an outsider, distanced and able to observe with clarity what others may be too close to perceive.

She very deliberately positions herself as an outsider, distanced and able to observe with clarity what others may be too close to perceive.

It may be an effect of her endearing “Irishness”, but Forde’s reasoning on the issues she raises is very persuasive. What she has to say is interesting in itself, but a great deal of the audience’s absorption comes from Forde’s vivid delivery. The attentive audience seems quite willing to put their faith in her, and she doesn’t disappoint, producing wonderful soundbytes to be rattled off at Stellenbosch dinner parties for months to come. Forde’s book is itself a masterpiece of quotable quotes, and she brings its energy to her discussion of various points of topical bearing, including the Protection of Information bill and the Rasputin-like presence of Mac Maharaj.

The audience itself is a curiosity, reflective perhaps of another problem. Predominantly over 60, mostly white, they are quite at odds with the youthful, more hip market Forde’s book seems aimed at. It lends to proceedings the air of a transplanted cocktail party. Midway through the discussion, it becomes clear that most of the attendees at the launch have not read Forde’s book, despite it having been on the market for a few months now. Rather, they are present to sound out their own opinions on Malema, to hear their own fears confirmed or validated, and to seek some sort of guidance from Forde on what is to be done about the impertinent inconvenient youth.

This one could surmise from the way the audience guffaws resonantly at Forde’s recollections of interviewing Julius, or how often she is stopped mid-sentence to elaborate on points which she glosses precisely because they appear in the book. But Forde handles it all imperturbably, steering the focal point from her back onto the audience by turning it into a Q&A dialogue. The question round of a lecture is often distressingly awful, but Forde is charmingly adept at giving bad questions good answers.

A good portion of the questions offered deal with typical Malema concerns. One middle-aged woman reflects aloud on Malema’s ability to draw on massive crowds, asking Forde, “Do you think we will see a local version of the Arab summer?” A Derrida-doppelganger invites Forde to comment on Malema’s potential rehabilitation over the coming years of his suspension. Others nod in telepathic sympathy with the question. Forde’s answer is to declaim any role on her part as forecaster of the future. But, she says, she wonders how long the current order will carry on, and who will take over when the proverbial house of cards collapses.

Forde ends her remarks by emphasising that there are two sides to Malema – the self-serving career politician, out to enrich himself; and the voice of conscience for an ANC that has failed to make the transition from liberation movement to political party. She offers no easy relief for those who hope that Malema has been neutralized, only the cautious hope that something positive may arise from the citizenry who are fed up with the ANC’s failure to deliver.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project