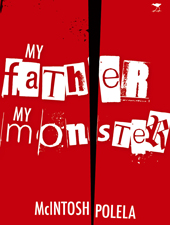

Launch of My Father, My Monster by McIntosh Polela, Centre for the Book, Cape Town

WAMUWI MBAO

The Cape Town book launch scene moves in ebbs and waves: there’s a certain protocol to these events: a glowing introduction from an academic compère, followed by twenty minutes of pronouncements on the matters at hand from the author whose name appears on the circulated e-fliers. Thereafter, questions dribble in from people who haven’t read the book, but wish to venture opinions anyway.

This, thankfully, was not the scene at the Centre for the Book in Cape Town, where the Centre for Conflict Resolution, an august body that dabbles in things literary and academic, hosted a panel discussion around McIntosh Polela’s recently launched memoir, My Father, My Monster (Jacana, 2011). Polela is the journalist-turned spokesperson of the Hawks, an enigma and figure of mystery to South Africans who have puzzled over his Cary Grant-esque accent. Polela’s book was launched in September 2011, and has since enjoyed a healthy run on the book-launch circuits up and down the country. This event was one of the CCR’s well-attended public dialogues, where academics, authors and those in the general know meet to break bread, as Cornel West would put it.

The event that took place within the wood-panelled confines of the Centre of the Book was somewhat more distinctive than the bland signings-and-sandwiches routine that usually occurs when an author is being punted for the attention of the nation’s literati. The panel was introduced by Garth Le Pere, a Ben Kingsley-esque figure who springs from one of those ambiguous think-tank consultancy firms and as such avoided the gooey morass of in-jokes we’re often forced to wade through before the main feature begins.

Le Pere introduced the author before an audience of about 40, noting that he, like most people, became aware of Polela as the “articulate ... confident and eloquent spokesman of the Hawks”. If one cringed somewhat at the inevitably back-handed gaffe of complimenting a black author in this way, it was soon forgotten as Le Pere went on to describe My Father, My Monster as “a journey of narrative, and a narrative of journeys”. This, Le Pere put forward, was the engaging leitmotif of the work we were assembled to appreciate. He further stressed how Polela’s was “a narrative of reconciliation, along two trajectories”: the first being the journey to come to terms with his mother’s disappearance from the life of the young McIntosh and his sister, and the second being the traumatic experience of finding and confronting their father, the man responsible for the murder of their mother.

When Polela himself took the floor, there was little for him to add. Sardonic, elegant but sparing in his discourse, he sensibly avoided retelling the memoir to the assembled audience. He described himself as “a man of few words”, even though his job revolved around speaking, and often being called upon to defend the indefensible. He gave a short account of the circumstances around the publication of the work, and followed that up with a few well-spun

McIntosh Polela

anecdotes that engaged the audience and made them feel like their patronage was worth the effort. This, after all, is part and parcel of the intriguing ritual that comprises book launching in this country. Polela closed his remarks by noting the positive way in which his story has been received by South Africans across the board, including traditionalists whom he expected to be against the warts-and-all baring of his family’s story.

If Polela himself was less than garrulous, his discussant Maureen Isaacson was unreserved in her praise for the work. “This book bleeds off the page”, Isaacson declared in an accurate assessment of a memoir that carries its heart on its crimson sleeve. In Isaacson’s eyes (her blurb decorates the front cover of My Father, My Monster – there are publishing customs that can’t be ignored), Polela’s is a story about betrayals and the wounds they leave, a potent theme given the reigning preoccupations of many literary works set in the apartheid era. Isaacson stressed how Polela’s book elucidates the commonplace nature of violence in South African society, and how it goes to interesting places in its exploration of the creation of masculinities under conditions of violence and displacement. Citing other memoirs by writers from Es’kia Mphahlele (Down Second Avenue) through Fred Khumalo (Touch My Blood) to Zakes Mda (Sometimes There’s a Void), Isaacson wondered whether there was something to be said about the consistent theme of gendered violence resonating through South African memoirs, an interesting question that deserves lengthier consideration on a separate platform.

Isaacson’s portion of the panel discussion proved to be the most fruitful from an academic point of view. She asked the audience to consider how we define monsters, relating her question to recent press debates concerning heinous crimes and those who commit them. She pointed out that McIntosh’s journey of coming to terms with his father’s actions is a story without closure, its ending deferred by the misrecognition that occurs at the moment of confrontation.

The event was well-attended, with questions from the audience being less of a painful ordeal than they can be at this sort of gathering. Half the questions dealt with the standard autobiographical concerns regarding family approval, the rites of first-time authorship, etc. The more interesting questions revolved around the significance of his name change – McIntosh dropped his father’s last name, something almost at odds with traditional African cultures. To this, McIntosh replied that his response to those who accused him of deserting tradition is always that “nothing about me has ever been traditional”. Indeed, for McIntosh, the name change symbolises the forming of a new, whole self a world away from the fractured individual whose trials are documented in the memoir.

The text itself will be reviewed shortly. But on the evidence of the dynamic and invigorating panel discussion that took place, it is clear that McIntosh Polela will be a notable figure on the literary scene for the next while.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project