Go to Prague in April when the magnolias are flowering in Ruska street. Stay with an ambassador. Open your window onto clock towers, pear orchards and birdsong. Get lost in Slavic diacritics and boulevards coloured like macaroons. All taxi drivers look like Milan Kundera.

(Wear dark glasses to obscure annoying family members.)

Have lunch bought for you at Francouzská restaurant by surgeons on the international conference circuit. Be reminded of the joke that God is not vain enough to think himself a surgeon, but be grateful for their mastery at mending the leaking threads of life.

Having cultivated a literary mentor, think of his injunction to look up Miroslav Holub, a wondrous Czech scientist-poet who wrote volumes with names like Vanishing Lung Condition. A stanza from “Nineveh” comes to mind:

Clay tablets wail:

These are bad times, the gods are mad,

Children misbehave

Everyone wants to write a book.

The ambassador bemoans graffiti. The cardiologist wants my telephone number. Our attentive sommelier shares a surname with Bohumil Hrabal, the literary genius who tumbled five stories to his death at the age of 83, feeding gutter pigeons outside his window. Two swans are gliding across the Vltava. Weirs render her flow into brocades of falling water. I think about my learned admirer while I cut into a roast pigeon.

Prague is a city of winged and fallen creatures.

The novel I served the King of England is Hrabal’s chef d’oeuvre. His protagonist Ditie is a diminutive waiter who finds a life purpose in losing his virginity in a brothel called Paradise.

It was all so wonderful and forbidden that I wanted nothing more in this world, and I resolved to save eight hundred and more a week selling hot frankfurters, because at last I’d found a beautiful and noble aim.

Haplessly amoral, Ditie crisscrosses history’s fault lines in Hrabal’s evocative prose, rich in comic absurdity and sparing in didactics. Despite being a dwarfish, Slavic untermensch, blond Ditie impregnates his Sudeten sweetheart for the Nazi master race breeding program. Ditie’s wife steals postage stamps from murdered Warsaw Jews and they buy a hotel on the proceeds of her theft. He is no longer a mere waiter, but a proprietor. He even stops feeling short. Their child is born retarded, becomes violent and is soon abandoned. Adam Thirwell asks: “What is the meaning of history? That is the central question of this novel. Everyone, in the end, is a waiter: a minor character.”

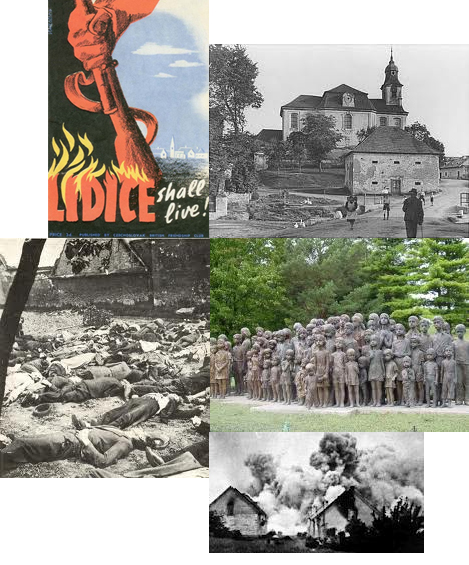

The Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia in 1938. Hitler’s blue-eyed boy Reinhard Heydrich, known as The Butcher of Prague, was assassinated by partisans in 1942. The Nazi reprisal was as brutal as it was arbitrary.

The village Lidice was condemned. All the men over 16 were shot against Horak the dairy farmer’s wall. The children were starved in an orphanage and made to write letters to their families the day before being gassed. The women were sent to concentration camps. Many went insane. Most were murdered. With unfathomable rationale, the Nazis filmed the methodical destruction of the village as propaganda to boost German morale. The Allied press made Lidice’s fate known around the world. Welsh miners collected money for the village to be rebuilt. Many Spanish and Mexican women were christened Lidice in sympathy. Towns, squares and streets in many continents were named after Lidice to frustrate the Führer’s desire to extinguish its very memory.

I went to Lidice with a young Czech the day before my lunch at Francouzská. In the way of all monuments it has a muted quality. It is constituted by absence. Where a town once stood is a large and peaceful park. Dandelions sprout in grouted pathways. The mass grave of men is enclosed by a dormant rose garden. The murdered children are remembered in individual sculptures.

In the novel Hrabal makes his protagonist Ditie come to the raised village, after helping a broken man to his feet on a Prague street. The broken man is a murderer from Lidice who spent ten years in jail, ignorant of his village’s fate. Ditie and the murderer walk through the night and the confused man falters when his bearings lead him to nothingness. One is reminded of WG Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, which travels the same ground as Hrabal, but does so in hindsight. Austerlitz is suffused with the melancholy spirit of abandoned buildings, haunted by the sadness of the world. The Polish poet Stanislaw Jerzy Lec said: “You can close your eyes to reality but not to memories.”

The waiter Hrabal at Francouzská restaurant rouses me from my contemplation with a dessert of strudels and cream. He pours sweet wine from a crystal decanter. I covet the garnet-shaded wine flutes engraved with somber looking owls. Artisans still carve the crystal that made the province of Bohemia an adjective for excellence.

Alena clears her throat and speaks for the first time: “Glass artisanship was tolerated under the communists because it was seen as ideologically unobjectionable.” She has strawberry hair and pastel-blue eyes, with a gait too weary for her young age. She works at the Israeli embassy and wants to show us the Jewish quarter as a courtesy to the ambassador.

“Please,” she says, pointing her arm ahead with eyes downcast, “I invite you.” She has a demeanour apposite to the weight of her inherited recollections. She takes us to the Jewish cemetery where a quarter of a million people are buried in layered tombs in an expanse meant for 25,000 graves.

The most illustrious buried personage is Rabbi Loew, the mystic and scholar who made the Golem from Vltava riverbank clay and brought him to life with incantations. This pottery Frankenstein outgrew his purpose to protect the ghetto from pogroms and frightened the gentiles. The rabbi eventually banished him to the attic of the Old New Synagogue where he now presides as a powerful tourist attraction. A child standing next to me asks his mother, “What is a rabbi?” His sibling answers: ”Someone who makes golems, you idiot.”

The girl with the strawberry hair smiles wearily.

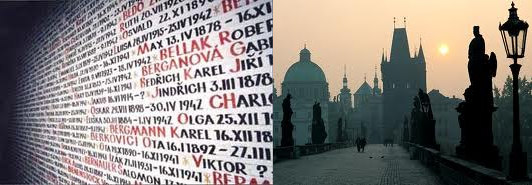

We end our tour at the Pinkas Synagogue. Written on the walls are the names of 77,297 Moravian and Bohemian victims of the Holocaust. Alena is a representative of what was once the largest Jewish population in Europe. She says it is her duty to remember what she calls “too much history”. She thanks me for being interested and waves as she walks away down Pariszka street.

I wait for the Ambassador and drink coffee at Café Kafka near the old town square, where the world’s oldest extant astronomical clock parades figurines of Apostles, Jews, Turks and skeletons on the hour. Clocks and organs were the most sophisticated man-made instruments before the Industrial Revolution. When the Hapsburgs gobbled up Bohemia an extraordinary law was passed requiring every village schoolmaster to compose and perform at least one Mass with his students yearly. This forced reconversion to Roman Catholicism was tempered by the law of unintended consequences. The Czechs are a nation of musical atheists. It has the world’s highest concentration of sheet music shops. Mozart called Prague his second home.

I am accompanying the ambassador to watch Il Trovatore as guests of the Italian delegation. We are driven up to the steps of the State Opera House in the ambassadorial car and the convenience makes me feel patriotic. Verdi’s opera is full of gypsies being blamed and burned. They are still spoken of as a menace here and called Roma. The gods are gilded and lined in red velvet and the singing is sublime. I compose a letter in my mind to my learned mentor, where I speak knowingly of this layered place with its feet in central Europe, its head in Paris and its industrial heart in Silesia (and cousins in the Balkans). Where intellectuals are revered. Where absurdity is accorded due gravitas. Where trams clang musically and Kafka’s statue in the wax museum has the sweating pallor of the true insomniac.

At intermission after champagne and egg-sandwiches I wait in a queue of ladies draped in furs. Graffiti in the marbled restroom reads:

Life without music is a mistake. Nietzsche

Suggested Reading

I served the King of England by Bohumil Hrabal

The Jingle Bell Principle by Miroslav Holub

Austerlitz by WG Sebald

Poems before and After by Miroslav Holub

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

I liked this piece and the photographs very much. A beautiful and sensitive snapshot of both Prague and the mind of her visitor – Dominique Botha .

Quite the contrast to a piece I read the day before about British stag and hen parties to Prague.

The haunting tale of Lidice is too horrible to comprehend. A story that makes you wish for amnesia. But, it must not be forgotten.

Thank you.