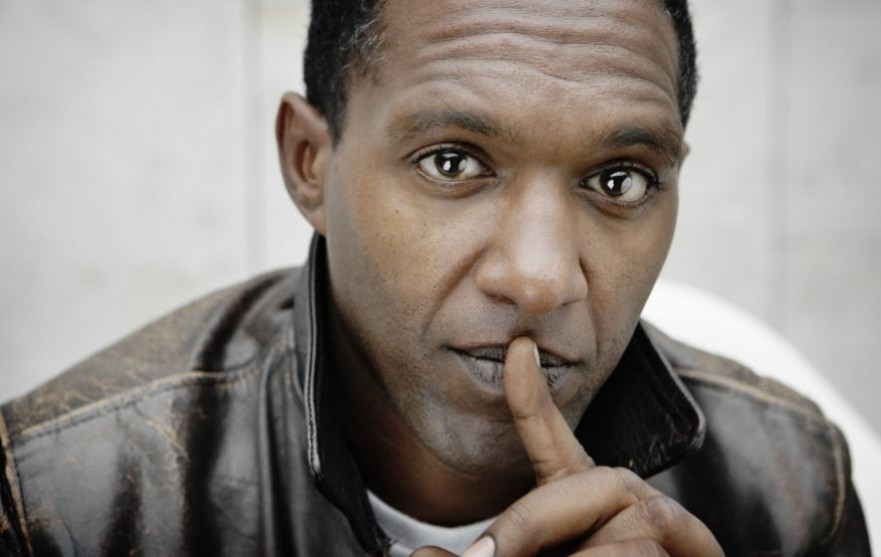

Lemn Sissay (Photo: James Ross)

After a breathtaking performance the previous night at the Slave Church on Long Street in Cape Town, Adrian Different and I are waiting for the charismatic and acclaimed British poet Lemn Sissay in the foyer of the Strand Tower Hotel. The air is crisp, like his poetry, and cuts to our bones. His debut collection, Tender Fingers in a clenched fist (1988), was published to wide acclaim and he has been touring the world with his poetry ever since. You can read more about Lemn Sissay here and here.

He arrives wearing stylish sunglasses that hide his eyes, and the three of us walk over to the Ethiopian Restaurant on Hout Street for some coffee. Our conversation is a bit stilted at first, as first encounters with strangers always are, but Lemn gradually lowers his guard, takes off his sunglasses and pretty soon we’re chatting away. We sit down on the mezzanine, make ourselves comfortable and order something to drink.

The waitress brings our coffee. Lemn looks at her while she puts the drinks down. As she walks away, he asks: “Sorry, but are you Ethiopian? There are certain things, your hair, your skin ...” She shakes her head: “Oh, no, but a lot of people have asked me that before.” Lemn keeps his charm going, reclining in his chair: “I can think that. But now I can see that you’re not. I am Ethiopian myself, so I have been there, and I would know.” She walks away, and I realise that Lemn uses his charisma for more than just poetry gigs.

We talk about the origins of his voice and then shift the conversation to his performance style. Adrian and I talked about the gig on our way back home the night before, and we were both fascinated by his performance, by the transformation of the words from the page to the stage. Lemn read his poems from a music stand, but he was very much present in the moment as the words followed each other. He had false starts and sometimes hesitated between stanzas, but he never gave the impression that it was because he lacked confidence or preparation. Rather, he was utterly in tune with the poems and respected them to the extent that he would start all over again if he felt he wasn’t doing them justice.

“Poets often don’t get that you have to think about every word. They’ll will read, catching a poem like you’d catch a wave,” Lemn explains. “I also do it sometimes. Your tonal pattern starts to hypnotise the poem in the same way that one hypnotises a snake. When this happens, the poem becomes impotent, over-stylised and the meaning is lost. The idea that I promote on stage is to speak the poem and to allow it to speak to you. It’s not just about listening to yourself, it’s also specifically about understanding and thinking about the things that you’re saying as you are saying them. And when I realise that I’m not doing that, I backtrack, I restart. This awareness prevents the stylistic hypnotism that can kill a poem. Your poem deserves to be thought about as you are reading it. You must treat it in the same way as you would another human being, a friend, a confidant, and you must reach the kernel of truth that you embedded in the poem when you first wrote it. That’s where I’m at.”

I take a sip of my coffee and ask: “Last night, I could hear that you were very in tune with the sounds that you were creating. You were incorporating jazz techniques like scatting, you made use of the full palette of vocal amplitudes, from very soft to feedback-inducing loud. How do you see the role of sound in the performance of a poem?”

Lemn shifts his eyes from the window and the street outside to me. “What I’m trying to do with the sound is to surprise myself. I like to go against the way the audience thinks – the way I think – the poem should be going.” Adrian becomes animated: “There was a point last night when you elevated your voice, throwing in high-pitched words every now and then. It drew me in, led my mind back to the heartbeat of the poem. It’s almost as if you were playing around with the sound of the words in the same way that a jazz musician would improvise on his sax.”

“Yeah, but the poem itself is never improvised. This is a really important and fundamental point for me about the process of writing. The poem stands as it does for particular reasons, and the sequence of words were specifically chosen. So that shouldn’t change. But when it comes to the process of performance no gig should be like the other. The poem should be explored, amplified, by the performance.” I think aloud about the analogy between poetry and music: “In that sense, a written poem is like a musical score and a reading (whether public or private) is like a performance of this score, a performance which can improvise on the score and do all sorts of things with it, especially if the reader is into jazz.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah!” Lemn adds enthusiastically. “The processes of composing and performing are two completely different acts. The writer loses control of the poem once it has been written. Whoever’s reading it takes the poem to other and interesting places which weren’t necessarily present in the original script. The idea of the poem as sheet music explains the dynamism between the written word and the same word when it is performed.”

We jump from one topic to another like kids on a jungle gym. Now we’re discussing the issue of poetry’s revolutionary potential. Lemn talks about the commodification of poetry through the “poetry scene”, through so-called revolutionary poets, through slams: “The consequence of the commodification of poetry is that it often takes out the very thing which defines it above all else. It is then that poetry loses its potential for revolution, when a poet is more concerned with his image than with his words.”

“It almost becomes a kind of pop-poetry,” Adrian adds. “Yeah, yeah, and most of these pop-poets will not be writing poetry any longer in ten years’ time, because they’ll realise that it doesn’t give them the fame they so desperately seek. If you’re looking for fame as a poet, you’re investing in the wrong profession. If you’re looking for truth, then you’re in the right place.”

“So, when do you think that poetry does in fact have the potential to be revolutionary?” I venture to ask.

“Always.” He pauses. “Last night was revolutionary, for instance, in its deliberate non-conformity. But there’s so much poetry that isn’t. I refuse to be cynical about it, although I do have my moments. It can get to you when you see mediocrity dressed up as something special. But cynicism doesn’t help anyone.”

“Because cynicism disarms the potential you have as a poet to use words as you would bullets, right?” I ask.

“Absolutely. One of the poems I performed last night, ‘Apple cart art’, criticises the mediocrity in contemporary poetry, especially at poetry slams. But the poem doesn’t get stuck in a cynical rut. It ends by saying that your greatest competitor should always be yourself when it comes to the creation of poetry. That is the only way in which poetry can be revolutionary.”

We let his words come to rest between us, wafting through the air like smoke. Then we remember that we’re actually busy with an interview and Adrian asks the next question: “All right, so what’s your conception of home?”

His face lights up: “Oh, it’s in me! Home is in me. It’s in my poetry as well. My poems are my family. They’ve been there for a long time, longer than any people have been, actually. I’ve been searching for my family my whole adult life and it’s funny, because I searched and searched, and then I figured, it’s me, I’m it. It’s a beautiful thing, but it took me a long time to get there. A long time. When I say that I’m my own family, it means everything. Families split-up, families have arguments, families mess up, and I am all of those things, they’re all in me. Fortunately, because I’m a one-man family, I can look to resolve things much easier and quicker than ‘normal’ families usually do. Isn’t that strange?” He becomes quiet for a while. His pause perches somewhere between melancholy and contentment.

“It’s one of the lucky things about not having a family. In realising that I have to be my own family, I can resolve things quicker, and it won’t get passed down to the next generation, you know? In many ways, I’m blessed. Who would’ve known? And this is where poetry becomes like family, like reflective glass. You can’t predict any particular kind of reflection. So you first write it, and then you see it. You see things in ways that you could never have predicted.”

Our coffee is finished. Lemn gets a call from a friend. He needs to go soon. We talk about his experiences as an outsider in South Africa over the last 15 years. He’s been here a number of times and knows the country quite well. We discuss the things that have changed and the things that haven’t. He tells us about the World Book Night in London where he’ll be performing tomorrow night, the MBE (Member of the British Empire) which he received from the queen, his love for Robert Greig’s poetry and Cape Town’s complex histories, the rise of the right in England, the unacknowledged legacies of the slave trade, the importance of honesty in poetry.

We pay the bill and head out. Lemn asks me to take a picture of him standing underneath the restaurant’s logo. The word ETHIOPIAN is lit up by blue neon lights and frames his figure. His eyes meet mine through the lens. They glow with a strange blue light.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project